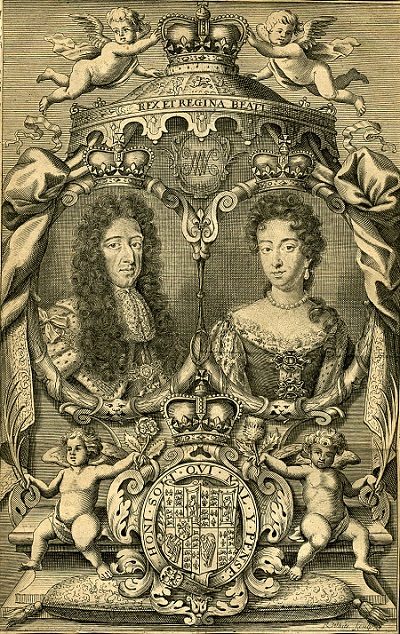

The Glorious Revolution in England occurred when Mary and William of Orange took over the throne from James II in 1688.

News of the Glorious Revolution had a significant and profound affect on the colonies in North America, particularly the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

When colonists learned of Mary and William’s rise to power it caused a series of revolts against the government officials appointed by James II.

What Was the Glorious Revolution?

The Glorious Revolution, also called the Revolution of 1688, occurred after William of Orange invaded England in November of 1688, pressuring James II to abdicate the throne of England to James II’s daughter Mary, the heir presumptive. Mary and her husband, William of Orange, officially became King and Queen of England in February of 1689.

James II was an unpopular King due to his conversion to Catholicism after his marriage to his second wife, a Catholic princess from Italy. James II also had faced increasing opposition as a result of his religious tolerance policies in 1685.

There was also talk that James II had been trying to form an alliance with the King of France Louis XIV, who was also a Catholic. Many feared a Catholic alliance between England and France would only strengthen Catholicism in Europe and establish a permanent Catholic monarchy in England.

As unpopular as the aging James II was, the public had simply hoped his beliefs and policies would die with him and they looked forward to his Protestant daughter, Mary, taking over the throne.

Matters took a turn for the worse though with the birth of James’s first son, James Francis Edward Stuart, which changed the existing line of succession by making the new son, also a Catholic, the first in line for the throne (because he was male) and his daughter Mary, second in line.

To prevent this from happening, several Tory leaders joined forces with Whig leaders and decided to invite William of Orange to England.

In November of 1688, William gathered supplies and forces and left Holland with 53 warships and hundreds of transport ships carrying 20,000 soldiers. His army crossed the North Sea and the English Channel and landed at Torbay in Devon on November 5.

It was the first invasion in England since William the Conqueror invaded in 1066. The date of William’s invasion was no coincidence either. William had deliberately planned for his Protestant invasion to take place on Guy Fawkes Night, the anniversary of the Protestant victory over Catholic conspirators in the Gunpowder Plot of 1605.

As William and his army marched their way to London over the next couple of weeks, they were met with virtually no resistance. On December 17, a group of Dutch guards arrived in London and escorted James II to jail in Rochester Castle in Kent.

A week later he was smuggled out of the jail with the help of some friends and lived the rest of his life in exile in France. On February 13, 1689 William and Mary became King and Queen of England.

It took time for news of the Glorious Revolution to reach North America but, when it did, it was welcomed with open arms, according to the book The Glorious Revolution in America:

“The Glorious Revolution in England was an unexpected but welcomed jolt to most colonists in America, particularly to those who saw it as a means of escape from an uncomfortable dilemma. The Popish Plot, Exclusion Crisis, Monmouth’s and Argyle’s rebellions, all the recent upheavals in England, had shaken the foundations of the Stuart establishment, but none was successful, none was large enough in conception, for colonists to feel included – although several made the attempt. None was sufficiently popular or contained strength enough to force changes upon Stuart institutions – except maybe in reaction – by which Englishmen in England, let along colonists, might benefit. The Glorious Revolution of 1688 was another matter; it got rid of one monarch and crowned two others. It was accompanied by popular support and promised several constitutional reforms which colonists were quick to appropriate, even exploit. For colonies were ‘contiguous,’ they said, and really ‘parts of the whole.’ Few Englishmen in the realm were convinced of this constitutional mateyness, and most were taken by surprise when colonists insisted upon a revolutionary role similar to their own.”

The Boston Revolt of 1689:

Massachusetts Bay colonists were delighted to hear about the revolution in England because it gave them an opportunity to finally rid themselves of the much despised Dominion of New England.

The Dominion of New England was a merging of the New England colonies, created by James II in 1686, that gave the crown tighter control of the colonies by replacing the local puritan-based governments with a royally-appointed government.

Massachusetts was the first colony to respond to the news of the revolution. When the news reached the Massachusetts Bay Colony in March of 1689, talk of an uprising began to quickly spread in Boston, which was the headquarters of the Dominion and its officials.

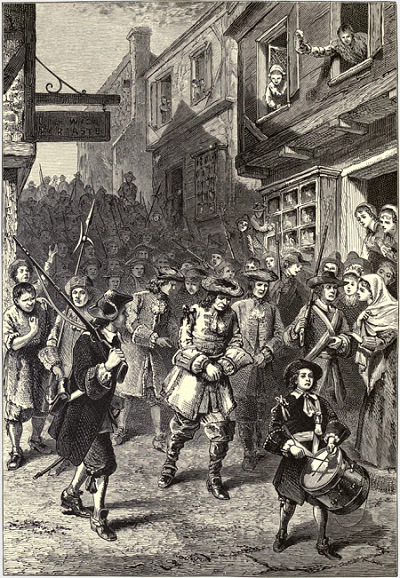

On April 18, a mob finally rose up and gathered in the streets of Boston to overthrow the governor of the Dominion of New England, Sir Edmund Andros. This became known as the Boston Revolt and is considered the New England version of the Glorious Revolution.

Andros a Prisoner in Boston, illustration by F.O.C. Darley, William L. Shepard or Granville Perkins, circa 1876

Andros took refuge in his quarters at a garrison house called Fort Mary near the channel at Fort Hill. Former Governor of Massachusetts, Simon Bradstreet, called for Andros to surrender but he refused.

Andros then tried to escape to the king’s frigate in Boston harbor, the Rose, but the militia intercepted the barge sent to bring him to the ship.

After tense negotiations, Andros surrendered and was first taken to the townhouse where his council assembled and then taken to the home of the dominion treasurer, John Usher, where he was held prisoner.

According to the book Protestant Empire: Religion and the Making of the British Atlantic World, once Andros was jailed, the Dominion of New England was over:

“Once the Massachusetts Bay colonists had imprisoned the governor of the Dominion, its foundations were shaken. Not only had questions about its legitimacy been raised by the revolution at home, but the Dominion was also undermined by the elimination of its governor and a number of the members of its appointed Council (also imprisoned in Boston.) After the Massachusetts coup, the Dominion ceased to function within New England. Other colonies followed Massachusetts’ lead and resurrected their former governments. Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Plymouth all went back to their older patterns and habits of governance while awaiting word from England.”

Shortly after, the Massachusetts Bay colonists set up a Council for Safety, which was led by Simon Bradstreet and included Jonathan Corwin and John Hathorne, who later became a judges in the Salem Witch Trials.

On May 22, the council voted to return the colony to its former Puritan-run government. The council handled affairs in the colony for a few months until official confirmation of a new regime came from William and Mary.

Meanwhile, Andros was held at Usher’s along with other Dominion officials until June 7, when he was transferred to Castle island. Some sources state that it was during this time period that Andros made an escape attempt while dressed in women’s clothing. Anglican minister Robert Ratcliff refuted this claim and stated it was merely “falsehoods and lies” designed to demean Andros.

It is true that Andros made an escape attempt during this time period, on August 2, after his servant got the sentries drunk. He fled to Rhode Island but was recaptured and held in solitary confinement.

Andros was held prisoner for 10 months until finally being sent to England to stand trial. The Massachusetts agents in London refused to sign the charges against Andros, so the court dismissed them and freed Andros.

The actions of the Massachusetts Bay Colony inspired other colonies that had been included in the Dominion to assert their own independence and reinstate their old charters as well.

Leisler’s Rebellion:

The Boston Revolt inspired a similar uprising in nearby New York, which had been merged into the Dominion of New England in 1688. Word of the Boston Revolt reached the Dominion officials in New York on April 26 but they made no mention of it or of the revolution in England out of fear of inciting an uprising in New York as well. Eventually though, word got out and a rebellion began to brew, according to the book Colonial New York:

“When news reached New England that James II had been overthrown in England and that William and Mary had seized the day, Bostonians arose in April 1689 to imprison Governor Andros and declare the Dominion defunct. That demise, combined with the story of probable French invasion, caused New York to reach a frenzy of excitement in mid-May. The towns on eastern Long Island, which had been planning to send a statement of grievances to England anyway, rose in revolt against the authority of Lieutenant Governor Nicholson, and they were soon joined by towns in Queens and Westchester Counties. They turned out appointees of the central government and elected others to replace them. On May 31 the New York City militia seized the fort in order to ‘save’ the colony, and on June 8 Jacob Leisler was commissioned as captain of the fort. Two months later he became commander in chief of the province. During these summer months the significant upheaval involved an effort by prominent older settlers, supported especially by the Dutch populace, to displace the insecure, newly emerged Anglo-Dutch elite. Although the rebels identified themselves politically (and expediently) with English whiggery, their program, such as it was, sought a restoration of traditional corporate liberties for communities rather than an enlargement of personal liberties for individuals and social groups.”

Protestant merchant Jacob Leisler has since been dubbed the ring leader of the rebellion in New York, but his role in the rebellion was not exactly that of an instigator. He does not appear to be an initiator in the rebellion but he did assume control over it once it started.

After taking control of New York, Leisler began organizing representatives in Massachusetts Bay colony, Plymouth colony and Connecticut colony to unite with New York and attack French Canada. Leisler found that the other colonies were reluctant to join him and also realized that although he had the support of the Dutch artisans and laborers, the merchants of New York were not behind him. Leisler jailed a number of people as punishment for not obeying his authority, which only made him more unpopular in the city.

In 1691, the new royal governor, Colonel Henry Sloughter, sent soldiers, led by Major Richard Ingoldsby, to secure the city but Leisler refused to let them into key forts in the city and refused to turn over the city to Ingoldsby.

The soldiers seized the city and, on the advice of prominent community leaders, Leisler, along with his son-in-law, was charged with treason. The two men stood trial, were found guilty and were sentenced to death. In May of 1691, both men were hanged until almost dead, disemboweled while still alive, beheaded and then their bodies were cut into quarters.

Leisler’s death made him a martyr and a hero. Colonists were so angry about his death that Sloughter had to allow for the formation of a representatives assembly. Several of the men elected to the assembly were Leisler supporters and, for many years after, the assembly was a battleground between them and supporters of the royal officials. According to the book Conspiracy Theories in American History, Leisler’s influence on the city continued long after his death:

“Despite the death of its prominent leader, Leisler’s Rebellion lived on in New York politics for decades to come, even after Parliament posthumously exonerated Leisler in 1695. Jacob Leisler’s conspiracy to restore Protestant rule to New York fueled an ongoing political struggle between elite and Leislerian factions that continued as New York’s various ethnic, religious and socioeconomic groups clashed over the future of the colony and its relationship to the throne. Like most popular uprisings, Leisler’s Rebellion was no mere coup, but an ideologically motivated effort to restructure power in the developing British North American colonies.”

Protestant Revolution in Maryland:

The rebellion in Maryland didn’t take place until the summer of 1689, long after King William and Queen Mary took over the throne in February of 1689.

For many decades prior to the Glorious Revolution, Maryland’s local government had slowly been taken over by Roman Catholics. Between the years 1666-1689, at least 14 of the 27 men on the local council were Roman Catholics. This council controlled the courts, militia and the land council.

After news of the Glorious Revolution in England reached Maryland, colonists became upset when Maryland’s government refused to recognize the new Protestant King and Queen of England.

The colonists began to arm themselves and in the summer of 1689, about 700 armed colonists calling themselves the Protestant Associators, led by Colonel John Coode, rose up and defeated an army led by Colonel Darnall.

After winning the battle, Coode and his puritan allies set up a new government in Maryland that outlawed Catholicism. Coode remained in power until a new governor, Nehemiah Blakiston, was appointed on July 27, 1691.

The Aftermath:

The overthrow of the Dominion of New England and of the officials appointed by James II was a significant victory for the American colonies. The colonists were freed, at least temporarily, of the strict laws and anti-puritan rule over the land.

The three colonies, Maryland, New York and Massachusetts, paid the consequences for their rebellion though, some more than others, according to the book Protestant Empire: Religion and the Making of the British Atlantic World:

“Faced with these three rebellions, the king and queen had to decide what to do with their self-proclaimed supporters. Although the justifications differed somewhat in the three rebellious colonies, Massachusetts, New York, and Maryland all presented their uprisings in the context of antipopery, liberty, and loyalty to the new monarchs. All three hoped for the crown’s support for what they had done. As royal policy developed in the aftermath of 1688, it became clear that the monarchs more or less accepted the rebellions in Massachusetts and Maryland, but not in New York. The reason for this variable response had to do with local conditions in each colony…In New York the rebels fared worst of all. With New York more deeply divided than Massachusetts and the divisions less easily sorted than the Protestant-Catholic divide in Maryland, the assertion that Jacob Leisler and his supporters represented the interest of the new monarchs was less apparent.”

Leisler’s critics, such as the former lieutenant governor Francis Nicholson, had turned on him and persuaded William and Mary that Leisler was not on their side. Yet it was Leisler’s own behavior that did the most damage.

When the royal governor, Henry Sloughter, was sent to take control of New York, he found Leisler fighting against the military commander Sloughter had sent because the officer had defied his authority. It appeared as though Leisler was more interested in his own power than that of the King and Queen and, as a result, he was tried and executed for treason.

The overthrow of the Dominion officials in the Massachusetts Bay Colony didn’t work out as the colonists had hoped either. Mary and William refused to reissue the colony’s original charter and instead issued a new charter in 1691 that merely continued the policies of the Dominion of New England, including restricting religious puritan-based laws.

The revolution and its aftermath also had negative long-lasting effects on the colonists themselves, in the form of increased anxiety and strife.

This tension may have been one of the underlying causes of the Salem Witch Trials, according to the book Protestant Empire: Religion and the Making of the British Atlantic World:

“No scholar has been able to come up with a perfectly satisfying explanation for the combination of circumstances that went into a witch hunt, but community anxiety helped to create conditions that could precipitate one. In Massachusetts the instability of the government compounded by fears that the local church order was being displaced set the stage, while in Scotland similar concerns over the traditional church were key. In both places a desire to combat atheism by proving that witches existed played a role, whereas in New England fear of Indian attack added to the sense of a community besieged. Both Massachusetts and Scotland were under the authority of a distant power – the crown in England – that seemed to threaten local control of religion, and both felt uncertain of their inability to maintain local commitment to a traditionally intrusive faith-based disciplinary system. In both instances such uncertainties created serious social strains that manifest themselves in witch-hunting.”

Although the rebellious colonists were successful at overthrowing James II’s rulers in the American colonies, the British government’s desire to gain more control over the colonies was unavoidable and continued to be a threat well into the next century.

Sources:

Lovejoy, David S. The Glorious Revolution in America. Wesleyan University Press, 1972.

Pestana, Carla Gardina. Protestant Empire: Religion and the Making of the British Atlantic World. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009.

Conspiracy Theories in American History: An Encyclopedia. Edited by Peter Knight, 2003.

Andrews, C.M. The American Nation: Colonial self-government, 1652-1689. Edited by Albert Bushnell Hart. Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1904.

“Richard Ingoldsby.” New York Unified Court System, www.nycourts.gov/history/legal-history-new-york/luminaries-legal-figures/ingoldsby-richard.html

“The Glorious Revolution.” BBC.com, British Broadcasting Copration, www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/civil_war_revolution/glorious_revolution_01.shtml

Rennell, Tony. “The 1688 Invasion of Britain That’s Been Erased from History.” Daily Mail, 18 April. 2008, http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-560614/The-1688-invasion-Britain-thats-erased-history.html

“What Was Leisler’s Rebellion.” New York Historical Society, www.nyhistory.org/community/leislers-rebellion

“The Great Boston Revolt of 1689.” New England Historical Society, www.newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/great-boston-revolt-1689/

Thank you, an excellent article!