Built in 1927, the Omni Parker House Hotel is a historic hotel in Boston, Massachusetts.

The original Parker House hotel was built in 1855 and a 10-story annex remained open for business while the main building was demolished and rebuilt in the 1920s.

Since a working hotel has operated on the spot since 1855, that makes it the longest continuously operating hotels in the U.S.

The hotel was founded by Harvey D. Parker, a 20-year-old farm boy from Paris, Maine, who arrived in Boston on a ship in 1825 with less than $1 in his pocket, according to Phyllis Meras in her book The Historic Shops & Restaurants of Boston.

Parker first worked in a stable and also, according Susan Carolyn Wilson in her book Heaven by Hotel Standards:The History of the Omni Parker House, worked for Dr. George Parkman, the doctor who later became the victim of the notoriously grisly Parkman-Webster murder case in 1849.

Harvey Parker later became a coachman for a wealthy Watertown woman. Parker would often drive the horse-drawn coach into Boston for his employer and would eat lunch at a small cellar cafe, owned by a man named John E. Hunt, on Court Square.

In 1832, Parker bought the cafe for $432 and renamed it Parker’s Restaurant. The cafe became very popular and was known for its excellent food and great service. In 1847, Parker took on a new partner, John F. Mills, and began making plans to build a hotel.

The Construction of the Parker House:

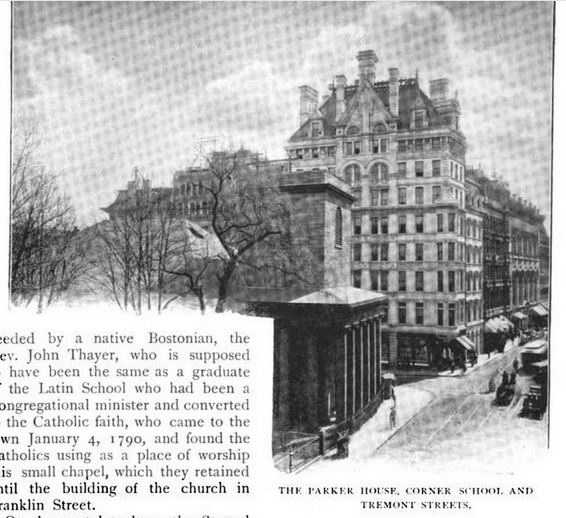

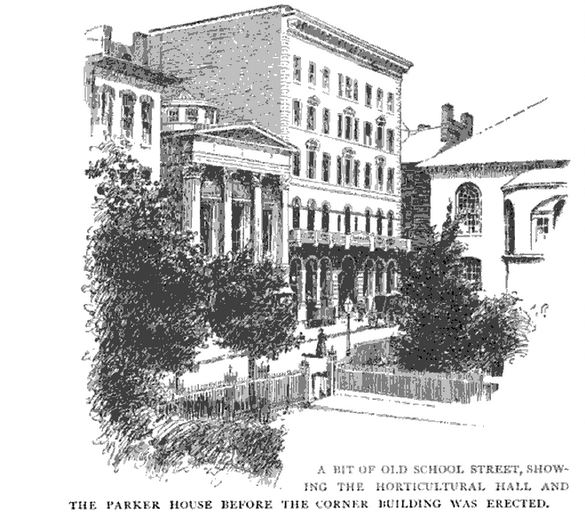

On April 22, 1854, Parker purchased the rundown old Mico mansion on the corner of Tremont and School Street and demolished it.

The Mico mansion had been built in 1704 for Boston merchant John Mico and was later bequeathed to Mico’s friend Jacob Wendell (the great-grandfather of Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr.,) in 1718. After Wendell died, Nicholas Boylston, a cousin of John Adams, took possession of the mansion and converted it into a hotel, known as the Boylston Hotel, in 1829.

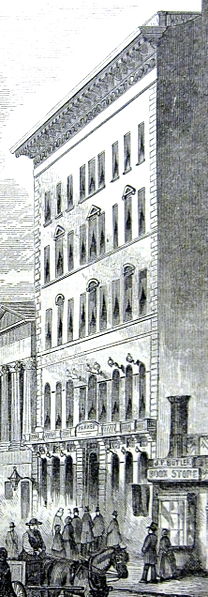

After Parker demolished the old mansion, he built a five story, Italian-style stone-and-brick hotel designed by architect William Washburn. The building was faced with white marble and featured arched windows, white marble steps and a marble foyer. Above the entrance was an engraved sign that read “Parker’s.”

According to Meras, the new building cast a large shadow on the historic King’s Chapel behind it but Parker found a way to remedy it:

“Because his chateau-like hotelry rose five stories and cut off light to old historic King’s Chapel behind it, legend has it that Parker installed Waterford crystal chandeliers in the chapel to compensate for natural light.”

Yet this seems unlikely since, as Wilson states, Parker disliked the chapel greatly and even wanted it demolished:

“Parker also reportedly disliked the gloomy old stone church that faced Parker’s on School Street – the ancient and honorable King’s Chapel. A captain named James Codman claimed Harvey once told him, ‘I wish they’d pull down that old King’s Chapel opposite. Such kinds of buildings aren’t no use in these times.’”

The Parker House Opens for Business:

In 1855, the Parker House hotel was finally completed and opened on October 8. The hotel was the first in America to use the “European plan,” meaning guests were only charged for the room and meals were paid for separately.

Prior to that, American hotels included meals with the price of the room but they were only available at set times and had limited menus.

Parker knew from his earlier restaurant experience that excellent cuisine was an important component of hospitality so he hired the gourmet French chef Sanzian for an annual salary of $5,000, at a time when most cooks earned about $418 a year.

Sanzian’s menu was a big hit, according to Wilson:

“Sanzian’s versatile menu drew large crowds and ongoing accolades. A typical Parker’s banquet of the 1850s or ‘60s might include green turtle soup, ham in champagne sauce, aspic of oysters, filet of beef with mushrooms, mongrel goose, black-breast plover, charlotte russe, mince pie, and a variety of fruits, nuts, and ice creams. Among Sanzian’s specialties were tomato soup, venison-chop sauce, and delicate mayonnaise, plus a distinctive method of roasting beef and fowl using a revolving spit over well-stoked coals.”

As a result, the Parker House hotel was hugely successful and received rave reviews from local newspapers, such as the Boston Transcript, which published the following review in October of 1855:

“This elegant new hotel, on School Street, was opened on Saturday for the inspection of the public. Several thousands of our citizens, ladies as well as gentlemen, availed themselves of the invitation, and for many hours the splendid building was literally thronged. All were surprised and delighted at the convenient arrangement of the whole establishment—the gorgeous furniture of the parlors, the extent and beauty of the dining hall, the number and different styles of the lodging rooms—and, in fact, the richness, lavish expenditure and excellent taste which abounded in every department. The house was universally judged to be a model one.”

The Boston Cream Pie Is Born:

In 1856, Sanzian reportedly invented the Boston cream pie that the hotel is now famous for. The pie is a two-layer French butter sponge cake filled with pastry cream and topped with chocolate fondant. The dessert has remained a staple of the hotel’s restaurant ever since.

The Boston cream pie became so popular it was later designated the official Massachusetts state dessert in 1996.

The Saturday Club Is Formed:

Due to the hotel’s location between the Boston Athenaeum on Beacon Street and the publishing offices of William D. Ticknor and James T. Fields, on the corner of Washington and School Street, the Parker House also became a literary hot spot in Boston.

In 1856, the Saturday Club, a group of writers, historians, scientists and philosophers began holding their monthly meetings over dinner at the hotel. The Saturday Club members included James Russell Lowell, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Charles Sumner, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr., and etc. The club would meet to gossip and discuss ideas, according to Heaven by hotel standards:

“The Saturday Club’s afternoons were often taken up with poetry readings, impassioned discussions, and book critiques. Indeed, according to enduring urban legends, some great moments in literary history transpired in these Parker House meetings. Here, in the folds of the Saturday Club, Longfellow drafted portions of ‘Paul Revere’s Ride,’ the idea for The Atlantic Monthly Magazine was born, and Dickens gave his first American reading of A Christmas Carol (All these claims have been contested, but none definitively proven one way or another.) As important to the group as intellectual pursuit, however, was camaraderie, and a hefty dose of mirth, gossip, revelry, and seven-course meals, all washed down with endless elixirs.”

When Charles Dickens stayed at the Parker House during his American lecture tour from 1867-1868, he often joined the Saturday Club’s meetings.

Other famous literary guests who visited the hotel around this time includes Mark Twain, Willa Carther and Edith Wharton.

One person who was not a fan of the Parker House was Henry David Thoreau. Although Thoreau was friends with many of the club’s members, he preferred the waiting room at the Fitchburg train station to the smoky Parker’s House hotel, according to his journal:

“As for the Parker House, I went there once, when the club was away, but I found it hard to see through the cigar smoke, and men were deposited about in chairs over the marble floor, as thick as legs of bacon in a smoke house. It was all smoke…The only room in Boston I visit with alacrity is the Gentlemen’s room at the Fitchburg Depot, where I wait for the cars [trains], sometimes for two hours, in order to get out of town. It is a paradise to the Parker House, for no smoking is allowed…I am pretty sure to find someone there whose face is set the same way as my own.”

The Parker House Expands:

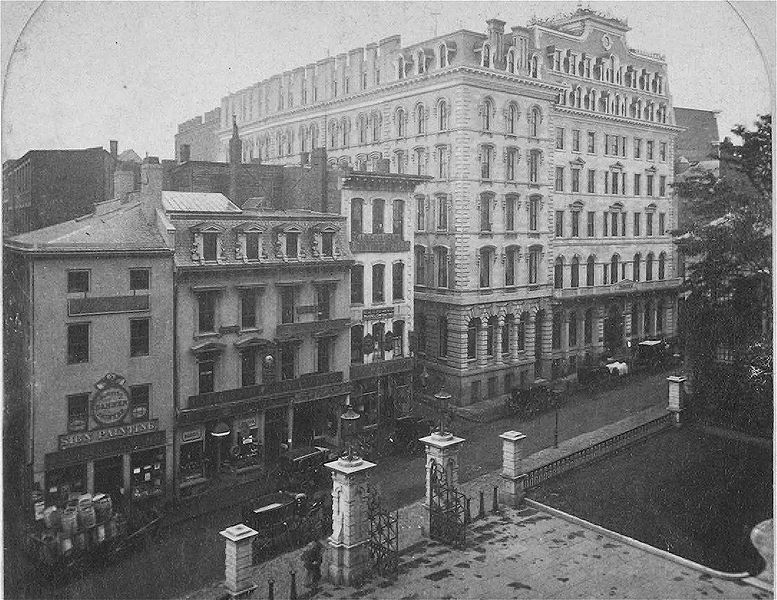

In 1860, Parker demolished the Horticultural Hall building next door, on the corner of Chapman Place and School Street, which was the site of the former Boston Latin School from 1748-1844 and still retained the old walls of the school. In its place, Parker built a six-story annex for the hotel.

In 1863, Parker acquired the land behind the annex building, on the corner of Chapman Place and Bosworth Street, and built another wing to the Parker House, a 10-story annex. This annex is still in use, making it the oldest part of the hotel, and is reportedly haunted.

In 1866, Parker purchased a narrow lot at 66 Tremont street and built a third wing for the hotel, complete with bay windows and a steep Mansford roof, and also added two floors to the main building.

In 1865, city officials built a new city hall on School Street and the Parker House suddenly became a meeting place for politicians due to its location between the new city hall and the Massachusetts State House on Beacon Hill. Both state and local politicians often met at the hotel to discuss politics over dinner and drinks.

Many notable political guests also stayed at the Parker House during the 1860s, including Mary Todd Lincoln, in November of 1862, while visiting her son Robert who was a student at Harvard.

Coincidentally, John Wilkes Booth also stayed at the hotel in the 1860s. Although Booth owned property on Commonwealth Ave, he never built a house on the lot so he often stayed at the Parker House when he was in town.

In July of 1864, Booth reportedly met with either Confederate secret agents or Confederate sympathizers at the Parker House hotel to hatch a plan to kidnap President Lincoln.

Booth’s kidnapping plan fell through but he later stayed at the hotel again on April 5 and 6 in 1865, just 10 days before he assassinated the president.

During Booth’s last visit to the hotel, an eyewitnesses said he saw Booth practicing his pistol shooting at a nearby shooting gallery, presumably Roland Edwards’ Pistol Gallery on Green Street.

The Parker House Rolls Are Born:

Sometime in the 1870s, the now famous Parker House rolls were invented. The rolls are a soft, folded bread roll with a crispy shell.

Legend has it the rolls were invented when a disgruntled German baker named Ward threw a batch of unfinished rolls into the oven after an altercation with a hotel guest. When the rolls came out of the oven, they had a folded shape that made them light and fluffy on the inside but with a crispy, buttery shell on the outside.

The rolls became so popular that through the 19th and 20th century, they were packaged and shipped from the kitchen to hotels, restaurants and stores across the country.

The Death of Harvey D. Parker:

On May 31, 1884, Harvey Parker died at the age of 79 and was buried in Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge. At the time of his death, Parker had a net worth of a little over $1 million dollars.

Since Parker’s two sons had died before him, the hotel passed to his business partners Edward O. Punchard and Joseph Beckman.

After Parker’s death, Punchard and Beckman decided to complete Parker’s dream to expand the hotel by adding yet another extension to the main building.

The extension was an elaborate, narrow, eight story-structure on the corner of Tremont and School streets, land which Parker had purchased in 1883. The addition was designed by architect Gridley James Fox Bryant and featured a marble-facade, a pavilion roof, and an iron balustrade.

In 1891, Joseph Reed Whipple, who had worked with Parker’s first partner, John F. Mills, took over management of the hotel, which he ran until his death in 1912.

Ho Chi Minh & Malcolm X at the Parker House:

During the early part of the 20th century, a number of now famous political leaders and activists worked in the hotel’s historic restaurant.

From 1912 to 1913, Ho Chi Minh, the Vietnamese Communist revolutionary leader, worked as a cook’s helper in the basement pastry kitchen.

Although hotel management and U.S. immigration officials have been unable to find any records of Minh’s employment at the hotel, Minh himself reportedly sent a postcard from Boston to Phan Chu Trinh in France in 1912 stating that he had been working as a cook’s helper at the Parker House in Boston.

Minh had left French Indochina in 1911 to travel and find employment. He worked as a kitchen helper on a French steam ship that made several stops on the East Coast of the United States, including New York City and Boston, where he decided to leave the ship and seek employment.

The marble table that Minh worked on is still located in the pastry kitchen today and has become something of a pilgrimage site for many Vietnamese people, according to an interview with a former bellman, Steve Mastrogiacomo, in the Boston Globe:

“The Ho Chi Minh table is also down in the bakery because he used to work here. A lot of people from Vietnam who aren’t even staying here will come in and ask to see the table. When I bring them down there, they stand there holding it and touching it. It’s cool to share that moment with them.”

In 2005, a Vietnamese delegation that included Prime Minister Phan Van Khai and Truong Quang Duoc, Vice President of the National Assembly, also visited the Omni Parker House to view the hotel and the Ho Chi Minh table in the pastry kitchen.

Coincidentally, a few decades later, yet another famous activist and political leader worked at the hotel when Malcolm Little, later known as the civil rights activist Malcolm X, worked as a bus boy at the hotel’s restaurant in the 1940s.

Another famous person who once worked at the restaurant was celebrity chef Emeril Lagasse who served as the Sous Chef in the Parker kitchens from 1979 to 1981.

The Parker House is Rebuilt:

In 1925, the Whipple Cooperation bought the Parker House from the Trustees of the Parker Estate and, on November 23, they closed the Parker House down in preparation for demolition in December, although the 80-room, 10-story annex on the corner of Chapman Place and Bosworth Street, remained open to guests.

Since the annex building remained open during the demolition of the main building, it has allowed the hotel to be described as the oldest “continuously operating” hotel in the country.

The old Parker House was demolished and replaced with a new 14-story building, made from polished black Quincy granite on the lower exterior facades and limestone and buff-colored brick above.

The new building, designed by architect G. Henri Desmond of Desmond & Lord Architects, was fireproof and featured oak paneling, plastered ceilings, crystal chandeliers, bronze-detailed doors and 800 guest rooms.

The Parker House reopened on May 12, 1927. To celebrate the hotel’s rebirth, the general manager Claude M. Hart,and his secretary, Alice Mulligan, flew over Boston harbor in a private plane where Mulligan ceremoniously threw the keys to the old Parker House building into the water below.

The Decline of the Parker House:

The celebration didn’t last long though because the financial crash of 1929 and the Great Depression that followed later put the the Parker House in financial trouble, as it did to most hotels in the country.

In 1933, the Atlantic National Bank foreclosed on the Parker House hotel’s mortgage. Then the First National Bank acquired the Atlantic National Bank along with its mortgage of the Parker House.

In February of 1933, Glenwood Sherrard purchased the Parker House, and the old 10-story annex behind it, for $3,300,000.

Sherrard took over management of the hotel and revived the struggling business. He continued to run the Parker House until his death in 1958.

During the 10 years that followed though, the Parker House fell on hard times again. Sherrard’s son, Andrew, managed the hotel but was known to make bad business decisions.

Dunfey Hotels Buys the Parker House:

In 1968, Dunfey Hotels bought the near-bankrupt Parker House from the Sherrard family and revived it, making many changes along the way, according to Wilson in her book Heaven by Hotel Standards:

“As might be expected, changes in ownership inevitably brought physical changes at the Parker House. The hotel’s basement area, once home to a billiard room, was supplanted by eateries like the English Grille Room and the first incarnation of The Last Hurrah, before it became the current fitness center (The Last Hurrah Bar is now located on street level off the main lobby.) The mezzanine-level lobby lounge, landing and reading library evolved into today’s cozy Parker’s Bar. An old banquet hall became the contemporary Press Room. The venerable Revere Room was updated into Cafe Tremont, which was adapted into a lobby-level meeting space called the Kennedy Room. And the 1935 Rooftop Terrace, closed in 1969, now hosts special functions. Bowing to modern needs for space, the eight hundred guest chambers of 1927 were restructured into 551 larger, uniquely shaped rooms and suites.”

In 1980, Dunfey Hotels bought the rights to Omni International Hotels name and in 1996, the Parker House name was changed to the Omni Parker House hotel.

In 2008, the hotel underwent a $30 million dollar renovation and the rooms were restructured into 530 guestrooms and 21 deluxe suites.

Sources:

Bross, Tom and Patricia Harris, David Lyon. DK Eyewitness Travel Guide: Boston. Dorling Kindersley Limited, 2001.

Turkel, Stanley. Built to Last: 100 + Year-Old Hotels East of the Mississippi. Author House, LLC, 2013.

Wilson, Susan Carolyn. Heaven by Hotel Standards: The History of the Omni Parker House. Omni Parker House, 2014, issuu.com/nieshoffdesign/docs/omniparkerbook

“Omni Parker House: A Brief History.” Omni Hotels, www.omnihotels.com/-/media/images/hotels/bospar/hotel/pdfs/parker%20house%20history.pdf?la=en

Bauer, Steve and Linda. Recipes from Historic New England: A Restaurant Guide and Cookbook. Taylor Trade Publishing, 2009.

Pulsifer, David. Pulsifer’s Guide to Boston and Vicinity With Map and Engravings. A Williams & Company, 1867. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=loc.ark:/13960/t6vx10434;view=1up;seq=15

Meras, Phillis. The Historic Shops & Restaurants of Boston: A Guide to Century-Old Establishments in the City and Surrounding Towns. The Little BookRoom, 2007

Pohle, Allison. “Secrets of bellmen from Boston’s most intriguing hotel.” Boston Globe, Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC, 2 Aug. 2015, www.boston.com/news/local-news/2015/08/02/secrets-of-bellmen-from-bostons-most-intriguing-hotel

Georgievska, Marija. “The Parker House Employed, Ho Chi Minh, Malcolm X & location of JFK’s proposal to Jackie Kennedy.” Vintage News, 27 Jan. 2017, m.thevintagenews.com/2017/01/27/the-parker-house-hotel-employed-ho-chi-minh-malcolm-x-the-location-of-jfks-proposal-to-jackie-kennedy/

Miller, Leslie. “Once Dunfey-Owned Omni Hotels Seek Bargains as Other Chains Divest Properties.” New Hampshire Business Review, 7-30 Aug. 1992, www.hampton.lib.nh.us/hampton/history/business/1990s/omnihotelsNHBR19920807.htm

Duiker, William J. Ho Cho Minh: A Life. Hachette Books, 2000

“Boston’s Literary Hotel.” Jet Setters Magazine, www.jetsettersmagazine.com/archive/jetezine/hotels/omni/parker/house.html

Booked July 16-19 2018 for a vacation, looking forward to spending some time in Boston. My wife and I are from the old whaling city New Bedford, MA

I hope our stay at the Parker House will be enjoyable. We did stay at Omni Mt. Washington in April of this year, and we had not so good time. The last full day, went out 9am return about 4pm, and found they forgot to clean our room, the bath towels were still on floor. Did complain about service, but management did not seem to care. Hope thing are better BOSTOM. Thanks Mike & Jean Texeira

Hope you have a great stay at the Parker House!