Proctor’s Ledge Memorial is a memorial dedicated to the 19 people who were hanged during the Salem Witch Trials in Salem, Mass. The memorial is at the base of Proctor’s Ledge, which is the location were the executions took place during the trials.

The memorial consists of a semi-circular granite wall with 19 stones engraved with the names and execution dates of the nineteen victims. A small oak tree, which symbolizes endurance and dignity, marks the center of the memorial.

The victims honored at the memorial are:

Bridget

Bishop

Sarah

Good

Elizabeth

Howe

Susannah

Martin

Rebecca

Nurse

Sarah

Wildes

George

Burroughs

Martha

Carrier

John

Willard

George

Jacobs, Sr,

John

Proctor

Alice

Parker

Mary

Parker

Ann

Pudeator

Wilmot

Redd

Margaret

Scott

Samuel

Wardwell

Martha

Corey

Mary

Easty

Another victim, Giles Corey, is not listed at the memorial because he wasn’t hanged at the site due to the fact that he was instead pressed to death, while being tortured by Sheriff Corwin, in a field on Howard Street, which is now the Howard Street Cemetery.

Who Designed the Proctor’s Ledge Memorial?

The design of the memorial was developed by landscape architect Martha Lyon, after she held a series of public hearings and meetings with the area’s residents for their feedback.

The memorial, as well as improvements to the streets and the land itself, were funded primarily through a $174,000 Community Preservation Act grant, as well as through donations, many from descendants of those executed at the site.

When Was the Proctor’s Ledge Memorial Built?

The memorial was built in 2017, to mark the 325th anniversary of the Salem Witch Trials, after the site had been officially confirmed in 2016 as the location of the Salem Witch Trials hangings.

How Was Proctor’s Ledge Identified as the Site of the Executions?

After the Salem Witch Trials were over, the site of the executions eventually became forgotten and it took many centuries for Proctor’s Ledge to be rediscovered, only for it to be forgotten yet again.

It appears that in the late 18th century, locals still knew that Proctor’s Ledge was the site of the executions because, in 1766, John Adams visited his brother-in-law in Salem and wrote in his diary that he had visited the ledge, which he referred to as Witchcraft Hill, a mentioned a number of locust trees that were later discovered to have grown on Proctor’s Ledge:

“Returned and dined at Cranch’s; after dinner walked to Witchcraft hill, a hill about half a mile from Cranch’s, where the famous persons formerly executed for witches were buried. Somebody within a few years has planted a number of locust trees over the graves, as a memorial of that memorable victory over the ‘prince of the power of the air.’ This hill is in a large common belonging to the proprietors of Salem, & c. From it you have a fair view of of the town, of the river, the north and south fields, of Marblehead, of Judge Lynde’s pleasure-house, & c. of Salem Village, &c” (Adams 199).

Yet, in 1867, historian Charles Wentworth Upham incorrectly identified Gallows Hill as the location of the Salem Witch Trials executions in his book, Salem Witchcraft, although he admitted in the book that it was only a guess and he might not be correct.

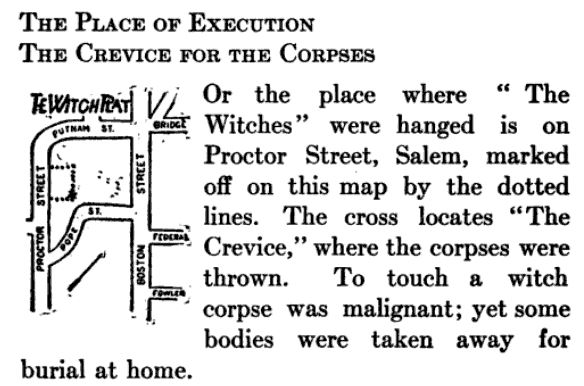

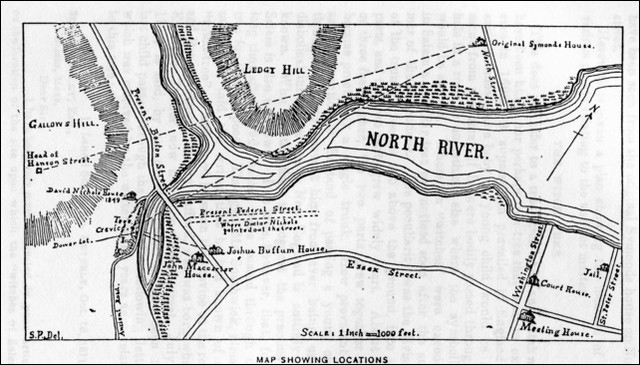

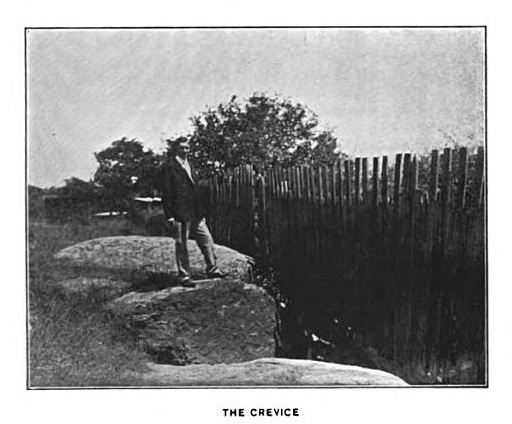

In 1911, a book titled A Short History of the Salem Village Witchcraft Trials by Martin Van Buren Perley was published and included a map that identified Proctor’s Ledge as the site of the executions. The map also identified a rocky crevice along side the ledge as the place where the bodies of the executed were temporarily placed.

In 1921, historian Sidney Perley identified Proctor’s Ledge as the site of the executions and presented detailed evidence to support his claim in an article for the Essex Institute Historical Collections.

As a result of Perley’s findings, in 1936, the city of Salem even purchased a small parcel of Proctor’s Ledge “to be held forever as a public park” and called it “Witch Memorial Land.” The site was never marked though and was eventually forgotten over time.

As historian Emerson W. Baker suggests, in an article on the Oxford University Press blog, this is probably because the trials have long been considered shameful and locals didn’t actually want to remember it:

“The witch trials have cast a long shadow over Salem’s history. For generations, many residents wanted to forget the trials, and refused to acknowledge their community’s role in one of the great injustices in American history. The fact that the execution site has been ‘lost’ more than once speaks to a collective amnesia and desire to forget.”

In 2010, Elizabeth Peterson, Director of Salem’s Corwin House, also known as the Witch House, assembled a team of experts to re-examine Perley’s research, a project titled the Gallows Hill Project.

The Gallows Hill team included Salem State professor and historian Emerson W. Baker, University of Virginia professor Benjamin Ray, author and historian Marilynne Roach and Salem State professor and geologist Peter Sablock.

After nearly six years of research, in January of 2016, the team officially confirmed that Proctor’s Ledge was the site of the Salem Witch Trials executions.

What Evidence Supports Proctor’s Ledge as the Execution Site?

The team analyzed multiple forms of evidence to confirm that Proctor’s Ledge was the execution site. For example, accused witch Rebecca Eames testified on August 19, 1692, that she and her guards had been traveling along Boston Road, which ran just below Proctor’s Ledge, and from her location at “the house below the hill” she saw some people at the execution of the accused witches that day, according to the court records:

“she was askt if she was at the execution: she was at the house below the hill: she saw a few folk” (SWP No. 44.1).

Marilynne K. Roach determined that the “house below the hill” was probably the McCarter House, or one of its neighbors on Boston street, and tried to determine if the ledge was visible from the houses on that street, according to Baker:

“Professor Benjamin Ray conducted research that pinpointed the McCarter house’s location and worked with geographic information system specialist Chris Gist of the University of Virginia’s Scholars Lab to determine whether, in fact, it was possible for a person standing at the site of the house on the Boston Street to see the top of Proctor’s Ledge, given the rising topography of the northeastern slope of the hill. Gist produced a view-shed analysis, which determined that the top of Proctor’s Ledge was clearly visible from the Boston Street house, as well as from neighboring homes. However, the traditional site on the top of Gallows Hill was not visible from the houses.”

Sidney Perley’s research indicates that similar evidence from another eyewitness, a nurse who was attending John Symonds’ mother as she gave birth to him in 1692, also confirmed Proctor’s Ledge as the site.

According to a letter written by Dr. Holoyoke after the death of John Symonds in 1791, which was later published in Upham’s book, the nurse who was assisting John Symonds’ mother at his birth later told John that she could see the accused hanging at the execution site from the window of the Symonds house that day:

“In the last month, there died a man in this town by the name of John Symonds, aged a hundred years lacking about six months, having been born in the famous ’92. He has told me that his nurse had often told him, that while she was attending his mother at the time she lay in with him, she saw, from the chamber windows, those unhappy people hanging on Gallows’ Hill, who were executed for witches by the delusion of the times” (Upham 377).

Perley identified the location of the house where Symonds was born, on North Street, and found that Gallows Hill is not visible from North Street because it is blocked by Ledge Hill yet Proctor’s Ledge was visible.

Although Upham also discussed Symonds story in his book, Salem Witchcraft, he assumed the house Symonds was born in was the same one he died in 100 years later and, because Gallows Hill is visible from that house, he used that as the sole piece of evidence to incorrectly identify Gallows Hill as the execution site.

Perley also interviewed Salem residents who knew the descendants of the accused and claimed the descendants told them the accused were executed on Proctor’s Ledge.

One such resident Perley interviewed was a man named Edward F. Southwick who lived with the great-great-granddaughter of John Proctor, Mrs. Nichols, as a boy and claimed that Nichols told him the accused witches were executed near the rocky crevice at Proctor’s Ledge:

“When a boy, Edward F. Southwick lived with David Nichols at this place, from 1847 to 1852, Mrs. Nichols was a Proctor, and a granddaughter of Thorndike Proctor, who was grandson of John Proctor, who was executed for witchcraft. Mr. Southwick stated to the writer and others that both Mr. and Mrs. Nichols told him that the witches were executed near the crevice. Mr. Southwick also said that an old man, who lived with Mr. Nichols, and who was named Thorndike Proctor and was a relative of Mrs. Nichols, used to take walks with him, and he also told Mr. Southwick that the witches were hung near the crevice.” (Perley pp. 15-16).

Perley also discussed an old family story from the Buffum family that states that after the executions on August 19, 1692, Joshua Buffum could see, from his house on Boston Street, George Burrough’s exposed hand and foot sticking out of the rocky crevice, so he later went over that night to cover them so they were no longer visible.

According to Perley, Gallows Hill is not visible from the site of Buffum’s house on Boston Street but the rocky crevice at Proctor’s Ledge is:

“The distance from the house of Joshua Buffum to the top of the hill [Gallows Hill] would make it improbable that a slightly exposed hand or foot could be seen. In an air line the distance is about one hundred and twenty rods, which is considerably more than a third of a mile. Not only was the distance great, but the growth of the trees, which must have existed to a greater or lesser extent in the common lands, would necessarily have precluded such a view. From the house of Joshua Buffum to the crevice, in an air line, the distance is only about fifty-three rods, and the view unimpeded, as one had to look down the hill and over the marsh and river only.” (Perley pp. 14-15).

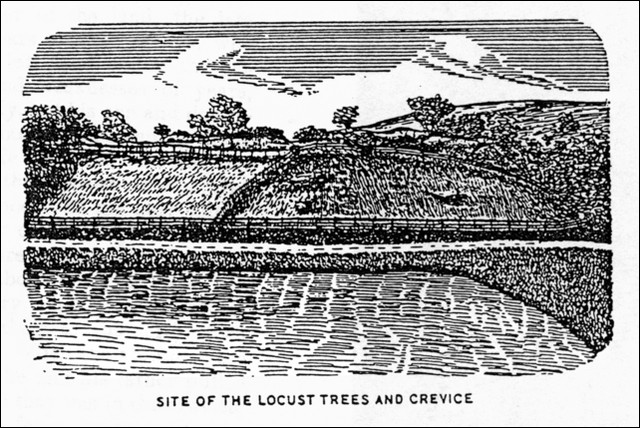

Other evidence includes the fact that when Perley first discovered Proctor’s Ledge in 1921, he asked the owner at the time, Solomon Stevens, if locust trees had ever grown on the hill, like John Adams had described in 1766. The Stevens family confirmed that there had been locust trees but they had been cut down years before:

“Through the infirmities and weakness of years, he [Solomon Stevens] was unable to talk intelligently, but his son and daughter said that there had been two large trees standing there, until about 1860, when the son felled them, and dug out the stumps, as the trees were in their garden. He pointed out the place where each had stood, – on the near side of the fence running along the brow of the ridge or hill at the left of the picture, – one where a little dot appears, and the other in the shrubbery about thirty or forty feet to the left of the first, at the very edge of the picture. The last-named tree (the one farthest to the left) stood in a crevice between the ledges..The writer has found neither evidence nor tradition that locust trees ever grew upon the top of Gallows hill; nor that a crevice ever existed there where the bodies of Burroughs, Willard and Carrier could have been partially buried” (Perley 13).

Another piece of evidence to support Proctor’s Ledge as the execution site is the fact that the some primary sources, such as Robert Calef’s book More Wonders of the Invisible World, state that the prisoners were carried to the execution site in a cart, yet Gallows Hill is much too steep for a cart to climb while Proctor’s Ledge is not.

Yet another piece of evidence is a local legend that states that after Rebecca Nurse’s execution, her son Benjamin rowed a boat that night from a creek near the Nurse homestead into the North River right up to the base of the hill where the execution took place so he could claim his mother’s body and give her a Christian burial on her property.

There are no waterways, and never have been, leading to Gallows Hill or anywhere near it. Yet, at the time of the trials, the North River used to spill out into a large bay that pooled into Bickford’s pond, which has since been filled in, at the base of Proctor’s Ledge, thus allowing Benjamin Nurse direct access in his boat to the execution site.

In addition, Proctor’s Ledge also has a rocky crevice running along side the ledge and, according to Calef, the bodies of the executed prisoners were temporarily placed in a rocky crevice at the execution site after they were cut down.

All of the evidence confirms that Proctor’s Ledge is the site of the Salem Witch Trials executions.

Other Salem Witch Trials Memorials:

In addition to the Proctor’s Ledge Memorial, there are other memorials in the Salem and Danvers area that are dedicated to the Salem Witch Trials victims.

One such memorial is the Salem Witch Trials Memorial, located on Liberty Street in Salem, which was built in 1992 to commemorate the 300th anniversary of the trials.

Another memorial is the the Salem Village Witchcraft Victim’s Memorial, located on Hobart Street in Danvers, which was also built in 1992 for the 300th anniversary of the trials.

For more historical sites in Salem, check out this article on the Salem Witch Trials historical sites.

Sources:

Calef, Robert.More Wonders of the Invisible World. Cushing and Appleton, 1823.

Baker, Emerson W. “A Memorial for Gallow’s Hill.” OUPblog, Oxford University Press, 13 Jan. 2016, blog.oup.com/2016/01/memorial-gallows-hill/

Perley, Sidney. “Where the Salem Witches Were Hanged.” Essex Institute Historical Collections, Vol. 57, No. 1, Jan. 1921, pp. 1-18

Perley, Martin Van Buren. A Short History of the Salem Village Witchcraft Trials. M.V. B. Perley, 1911.

Upham, Charles Wentworth. Salem Witchcraft: With an Account of Salem Village. Vol. II, Wiggin and Lunt, 1867.

Adams, John. The Works of John Adams. Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1850.

Woodside, Christine. “The Site of the Salem Witch Trials Hangings Finally Has a Memorial.” Smithsonian, 13 July. 2017, www.smithsonianmag.com/history/site-salem-witch-trial-hangings-finally-has-memorial-180964049/

“SWP No. 044: Rebecca Eames.” Salem Witch Trials Documentary Archive and Transcription Project, salem.lib.virginia.edu/n44.html#n44.1

“City of Salem Announces Plan for Memorial at Proctor’s Ledge.” City of Salem Ma, www.salem.org/city-salem-announces-plans-memorial-proctors-ledge/

“Proctor’s Ledge Memorial Project.” City of Salem Ma, www.salem.com/proctors-ledge-memorial-project

“Proctor’s Ledge Memorial.” Salem Witch Museum, salemwitchmuseum.com/locations/proctors-ledge-memorial/