The Daughters of Liberty was a group of political dissidents that formed in the North American British colonies during the early days of the American Revolution.

The following are some facts about the Daughters of Liberty:

Much like the Sons of Liberty, the Daughters of Liberty was created in response to unfair British taxation in the colonies during the American Revolution, particularly the Townshend Acts of 1767 which were a series of measures that imposed customs duties on imported British goods such as glass, paints, lead, paper and tea.

Although some sources state that the Daughters of Liberty was an official group or society of women, other sources indicate it was more of a blanket term used to describe all women who supported the patriotic cause.

According to the book Household Manufacturers in the United States (which discusses how women’s crafting skills helped contribute to the American Revolution) the Daughters of Liberty was an actual society that had chapters in many sections of New England.

Another book, titled Civil Disobedience: An Encyclopedic History of Dissidence in the United States, also states there were many official chapters of the society, particularly in Rhode Island:

“In 1766, the city’s female auxiliary, the Daughters of Liberty, became the first group to formalize their organization under that name. That same year, Eleanor Frye founded a Daughters of Liberty unit at East Greenwich; another group gathered at the home of Mary Easton Lawton and Robert Lawton at Spring and Tomo Streets in Newport.”

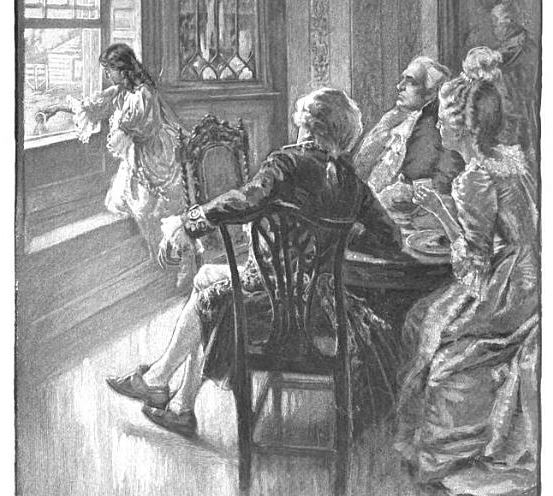

A Patriotic Young Woman, illustration published in Our Country: A Household History for All Readers, circa 1877

When Did the Daughters of Liberty Form?

The name, the Daughters of Liberty, first began showing up in the press around 1766, when the Boston Gazette published an article on April 7 of that year about a recent spinning bee held at a house in Providence, Rhode Island:

“On the 4th instant, eighteen daughters of liberty, young ladies of good reputation, assembled at the house of doctor Ephraim Brown, in this town, in consequence of an invitation of that gentlemen, who had discovered a laudable zeal for the introducing Home Manufacturers. There they exhibited a fine example of industry, by spinning from sunrise until dark, and displayed a spirit for saving their sinking country, rarely to be found among persons of more age and experience.”

Yet, according to the book Understanding the American Promise, the Daughters of Liberty didn’t officially emerge until 1768, after the passage of the Townshend Acts the previous year:

“The Townshend duties thus provided an unparalleled opportunity for encouraging female patriotism. During the Stamp Act crisis, Sons of Liberty took to the streets in protest. During the difficulties of 1768 and 1769, the Daughters of Liberty emerged, embodying the new idea that women might play a role in public affairs. Any woman could express affiliation with the colonial protest through conspicuous boycotts of British-made goods.”

What Did the Daughters of Liberty Do?

The Daughters of Liberty didn’t join in on the public protests and riots incited by the Sons of Liberty in 1765. Instead, they organized and participated in boycotts and helped manufacture goods when non-importation agreements caused shortages.

In August of 1768, when Boston merchants signed a non-importation agreement in which they pledged not to import or sell British goods, this caused a shortage in the colony of specific goods like textiles.

To help ease this shortage, the Daughters of Liberty organized spinning bees to spin yarn and wool into fabric, according to the book The American Revolution: A Concise History:

“Women took to their spinning wheels – what had been a chore for solitary women, spinning wool into yarn, weaving yarn into cloth, now became a public political act. Ninety-two ‘Daughters of Liberty’ brought their wheels to the meeting house in Newport, spending the day spinning together until they produced 170 skeins of yarn. Making and wearing homespun cloth became political acts of resistance.”

When the colonists also decided to boycott British goods, particularly British tea, women joined in on the boycott. Since women were the ones who purchased consumer goods for their households, and some of them also ran small shops themselves, their actions had a major impact on British merchants, according to the book Revolutionary Mothers:

“But when the call went out for a boycott of British goods, women became crucial participants in the first organized opposition to British policy. Thus, the first political act of American women was to say ‘No.’ In cities and small towns, women said no to merchants who continued to offer British goods and no to the consumption of those goods, despite their convenience or appeal. Their ‘no’s had an immediate and powerful effect, for women had become major consumers and purchasers by the mid-eighteenth century. And in American cities, widows, wives of sea captains and sailors, and unmarried women who ran their own shops had to make the decision to say no to selling British goods. In New York City a group of brides-to-be said no to their fiances, putting a public notice in the local newspaper that they would not marry men who applied for a stamped marriage license. Parliament could ignore the assemblies petitions. It could turn a deaf ear to soaring oratory and flights of rhetoric. But Parliament could not withstand the pressures placed on it by English merchants and manufacturers who saw their sales plummet and their warehouses overflow because of the boycott. In March 1766, the Stamp Act was repealed.”

In addition to boycotting the purchase of tea, women also signed agreements pledging that they would also not drink any tea offered to them. In Boston on January 31, 1770 the Boston Evening Post published the following agreement, reporting that over 300 Boston women had signed it:

“At a time when our invaluable rights and privileges are attacked in an unconstitutional and most alarming manner, and as we find we are reproached for not being so ready as could be desired, to lend our assistance, we think it our duty perfectly to concur with the true Friends of Liberty, in all the measures they have taken to save this abused country from ruin and slavery; And particularly, we join with the very respectable body of merchants, and other inhabitants of this town, who met at Faneuil Hall the 23d of this instant, in their resolutions, totally abstain from the use of tea: And as the greatest part of the revenue arising by virtue of the late acts, is produced from the duty paid upon tea, which revenue is wholly expanded to support the American Board of Commissioners, we the subscribers do strictly engage, that we will totally abstain from the use of that article (sickness expected) not only in our respective families; but that we will absolutely refuse it, if it should be offered to us upon any occasion whatsoever. This agreement we cheerfully come into, as we believe the very distressed situation of our country requires it, and we do hereby oblige ourselves religiously to observe it, till the late Revenue Acts are repealed.”

This same statement was also published on February 12 in the Boston Evening Post and similar statements were published on February 15 in the Boston Weekly News-letter and the Massachusetts Gazette.

To get around purchasing and drinking British tea, women found alternatives by making herbal teas from various plants like raspberry, mint and basil, which they referred to as Liberty Tea.

The Daughters of Liberty weren’t always so well-behaved though and sometimes took matters into their own hands when they deemed it necessary.

In 1777, these women even had their own version of the Boston Tea Party, later dubbed the “Coffee Party,” during which they confronted and assaulted a local merchant who was hoarding coffee in his warehouse. Abigail Adams described the incident in a letter, dated July 31, 1777, to her husband John Adams:

“You must know that there is a great scarcity of sugar and coffee, articles which the female part of the state are very loathe to give up, especially whilst they consider the scarcity occasioned by the merchants having secreted a large quantity. There has been much rout and noise in the town for several weeks. Some stores had been opened by a number of people and the coffee and sugar carried into the market and dealt out by pounds. It was rumoured that an eminent, wealthy, stingy merchant (who is a bachelor) had a hogshead of coffee in his store which he refused to sell to the committee under 6 shillings per pound. A number of females some say a hundred, some say more assembled with a cart and trucks, marched down to the warehouse and demanded the keys, which he refused to deliver, upon which one of them seized him by his neck and tossed him into the cart. Upon his finding no quarter he delivered the keys, when they tipped up the cart and discharged him, then opened the warehouse, hoisted out the coffee themselves, put it into the trucks and drove off. It was reported that he had a spanking among them, but this I believe was not true. A large concourse of men stood amazed silent spectators of the whole transaction.”

Members of the Daughters of Liberty:

There is no known list of members of the Daughters of Liberty but many notable women contributed to the cause and played a variety of roles in the American Revolution.

One such woman was Sarah Bradlee Fulton from Boston, who has since been called the “Mother of the Boston Tea Party.” According to the Boston Tea Party Museum website, she is credited with the idea of disguising the men as Mohawk Indians, painting their faces, and donning Native American clothing.

After the Boston Tea Party was over, Fulton helped dispose of the men’s disguises and cleaned the red paint off their faces. In June of 1775, after the Battle of Bunker Hill, Sarah Bradlee Fulton organized a small field hospital next to Wade’s tavern and asked women to serve as nurses to the soldiers wounded in the battle. She served as a nurse herself and even removed a bullet from a young soldier’s cheek.

During the Siege of Boston, Sarah Bradlee Fulton also confronted a group of soldiers who had seized a shipment of wood that she and her husband had bought for the sole purpose of keeping it out of the hands of the British troops.

When Fulton heard the troops had seized it, she chased the men down, grabbed their oxen by the horns, turned them around and commandeered the shipment. When the troops threatened to shoot her she simply replied “shoot away.” Amazed by her defiance, they surrendered the shipment to her.

A chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution was later named after Fulton and a memorial plaque was placed at her grave site in 1900. The following poem, written by Mary Jane Seymour, was read at the dedication ceremony for the plaque:

Yet not alone by men reclaimed

Brave women too achieved their part

With courage, love and loyalty,

They bore war’s cruel smart

We turn no printed page to-day,

Their gracious deeds to magnify

Within our hearts their memories rest,

Their influence cannot die.

We raise this modest table stone

Our sister’s name and fame to keep

The impress of her noble life

Ends not with a dreamless sleep –

May we be wise and ever prize,

The lessons taught us here,

That freedom comes by sacrifice

And duty knows no fear.

Another notable Daughter of Liberty was actually a young girl, Susan Boudinot, the nine-year-old daughter of the future President of the Continental Congress Elias Boudinot, who made the pledge not to drink British tea and stuck to her promise.

While visiting the home of New Jersey’s Loyalist Governor, William Franklin, she was served a cup of tea and after refusing it multiple times she then accepted it politely, crossed the room and threw the tea out a nearby window.

Boudinot became famous for her rebellious act and even 100 years later magazines, such as St. Nicholas: An Illustrated Magazine for Young Folks, were still publishing poems and drawings about her defiance.

Little Susan Boudinot, illustration published in St Nicholas: An Illustrated Magazine for Young Folks, Volume 26, circa 1899

According to the Report of the National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution from 1917, there were numerous other notable women who supported the cause and later had DAR chapters named after them:

“The following is a enumeration of the more prominent patriots from whom chapters have been named, but it by no means covers the list: Molly Pitcher (Mary Ludwig Hays), of Monmouth, N.J., who took her husband’s place (when he was dangerously wounded) at the canon for 24 hours at the Battle of Monmouth, received the personal thanks of Gen. Washington and from the Continental Congress, a sergeant’s commission, and half pay through life; Sarah Bradlee Fulton, ‘mother of the Boston Tea Party’ and the messenger of Gen. Washington inside enemy’s lines in Boston; Lydia Darrah, whose eavesdropping and daybreak ride to the grist mill save the army of Washington; Nancy Hart, of South Carolina, who single-handed captured six Tories; Emily Geiger, of South Carolina, who rode 50 miles on horseback through country infested by British, carrying a message from Gen. Greene to Gen. Sumter, was captured, searched (after she had swallowed her dispatches), released, and gave the message verbally; Deborah Sampson, of Massachusetts, who fought as a common soldier for two years; Rebecca Motte, of South Carolina, who set fire to her own house to prevent it from falling into the hands of the British; Prudence Wright and the women of Pepperell, Mass., who guarded the bridge at Pepperell and secured, by capture, a Tory carrying dispatches; Elizabeth Zane, of Virginia, who carried (under fire by the British and Indians), powder in a tablecloth from the powder house to the fort, a distance of 100 yards, and thus saved the day at Fort Henry, Va.; to Hannah Arnett, a frail little woman who uttered living words at a vital moment and brought about the rejection of the British offer of amnesty and turned the tide of the American Revolution.”

Through their various roles, these Daughters of Liberty made their own contributions to the American Revolution and helped win America’s freedom in their own way.

Sources:

Berkin, Carol. Revolutionary Mothers: Women in the Struggle for America’s Independence. Alfred A. Knopf, 2005.

Green, Mary Wolcott. The Pioneer Mothers of America; Harry Clinton Green. G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1912.

Report of the National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution, Volume 19. Government Printing Office, 1917.

Representative Women of New England. Edited by Julia Ward Howe and Mary Hannah Graves. New England Historical Publishing Company, 1904.

“Sarah Bradlee Fulton.” Boston Tea Party Ship & Museum, Historic Tours of America, www.bostonteapartyship.com/sarah-bradlee-fulton

St. Nicholas: An Illustrated Magazine for Young Folks, Volume 26. The Century Co, 1899.

Allison, Robert. The American Revolution: A Concise History. Oxford University Press, 2011.

Roark, James L. and Michael P. Johnson, Patricia Cline Cohen, Sarah Stage, Alan Lawson, Susan M. Hartmann. Understanding the American Promise, Volume 2: From 1865. Bedford/St. Martin’s 2011.

Tryon, Rolla Milton. Household Manufactures in the United States, 1640-1860. University of Chicago Press, 1917.

Zinn, Howard. A People’s History of the United States; 1492-Present. Routledge, 1980.

Lossing, Benson J. Our Country: A Household History for All Readers. Johnson & Miles, 1878.

Thank you so much this will be the best report have ever done thanks to your articles.

You’re welcome, Haileigh!

I believe I have family in this, my name is Elaine DuBose Willard. I would be very interested in finding out any information.

I met a lady touring a home in Mobile, Ala. told her my maiden last name which is Du Bose, strange, her last name is Du Bose. She told me to talk to her sister, Cheryl Hollick, which is in the Daughters. Any help would be great! Thank you!

This is a good article for reports

Great it helps with my report. Lots of primary sources

Great article! Love the illustrations.

Unfortunately I see no mention of Prudence Cumings Wright, the Captain of the Bridge Guard, who arrested a tory in April 1775 at Jewett’s Bridge in Pepperell, Mass. This would be a wonderful addition for future reference, were you to ever revise the article.

Wendy Cummings

Regent, Prudence Wright Chapter

Daughters of the American Revolution

Hi Wendy, Prudence is mentioned in the article and I also wrote an additional article entirely about her titled Prudence Cummings Wright & Leonard Whiting’s Guard. She was a very brave and fascinating woman!

I have to do 10 or more facts about the daughters of liberty but from reading this whole article, I GOT 21 FACTS THANKS TO THIS WHOLE ARTICLE!!!!! Whoever made this (Sorry I didn’t say the name i’m too lazy XD) is a really smart and the best helpful person ever!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! 🙂 ;-;

this is very useful even when you cant find any thing in books that is why i like to use computers this so amazing and it has so many different topics anny OUT

hey i love your articles there awesome

Thank you for this info. This has been help full for my social studies project

Awsome but if you included how many daughters of Liberty their were that would be great!

There isn’t an exact number because it was a loose organization of like-minded women, not an official club or group.

Hi there

Can I ask if you have a copy of the exact article published by the Boston Gazette , I’m trying to look for an original copy of it .

thanks

Sorry, I don’t have a copy of it.

this is great info for school.

My DAR chapter is named for Susannah Smith Elliott of South Carolina. When the British came to her land they took many animals and other things they needed or wanted. After they left, she found one fowl they had missed and took it to them to show “Southern hospitality.” She also hid men from the soldiers in a secret closet in her home.

Reference: homepages.rootsweb.com/~showe/SusannahSmithElliott/Susannah.html

Omg I was spending a at least 30 minutes to find a way to learn daughters of liberty and then you know what I just found and it was AMAZING make more of these i am going to learn so much and I already did.