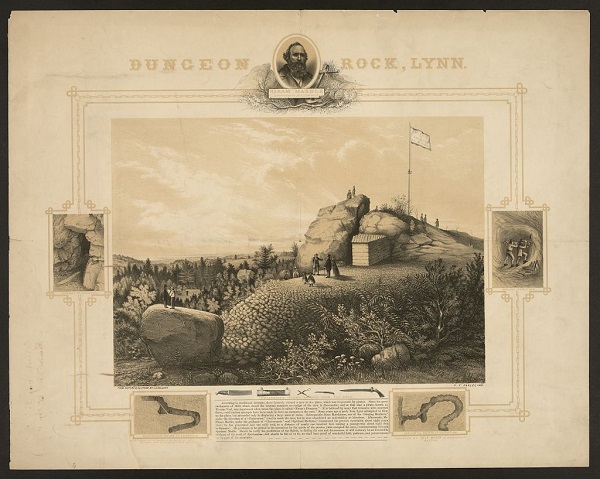

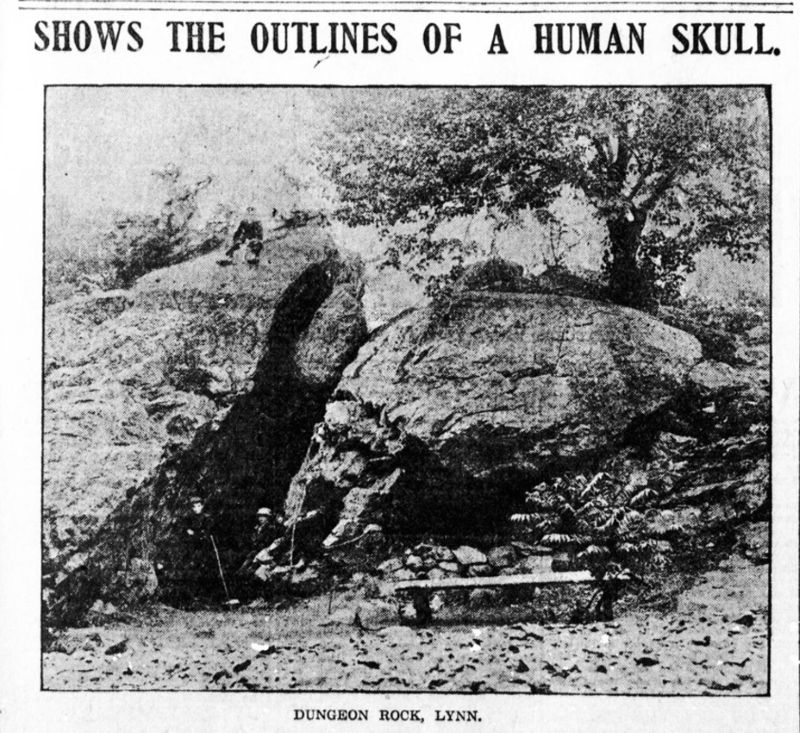

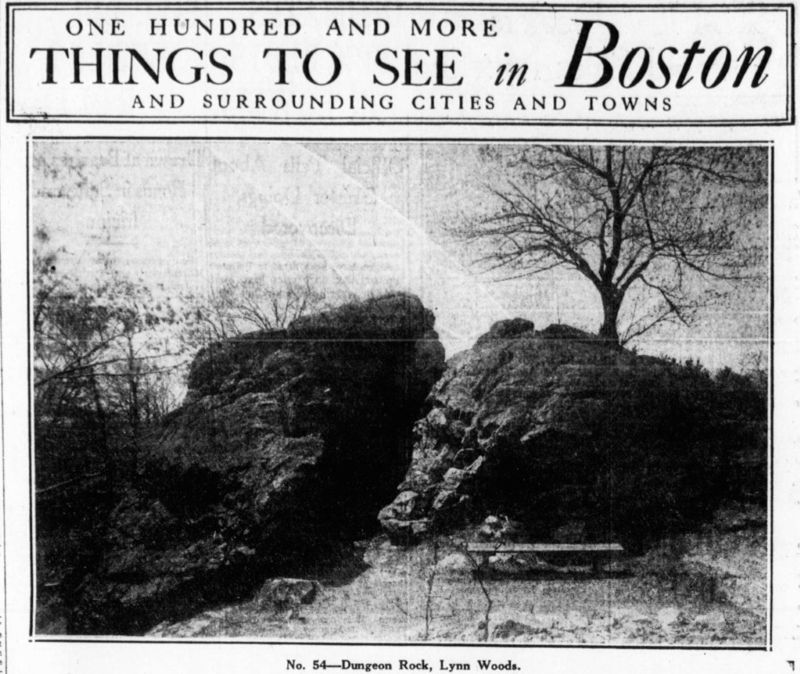

Dungeon Rock is a historic rock formation in Lynn, Massachusetts, that features a cave where a pirate was reportedly buried alive with his treasure during an earthquake in 1658.

The pirate’s name was Thomas Veale, and it was believed that he was hiding out in the cave while trying to avoid authorities, according to a book published in 1829, titled The History of Lynn, by a Lynn writer and publisher named Alonzo Lewis.

Lewis states that Veale and three other fellow pirates found the cave some time before when locals saw them anchor offshore in their ship one evening and row up the river in a small boat. It is said that they landed somewhere up river and then disappeared into the Lynn Woods.

The following morning, the pirate ship was gone, and no trace of the pirates could be found. That same morning, though, a mysterious note was found at the local Iron Works requesting that an order of iron shackles, handcuffs, hatchets, and other items be made and left in a secret location in the Lynn Woods in exchange for an amount of silver.

The ironworkers made the items in a few days and left them in the designated drop spot. The following morning, the items were gone, and the money had been left in their place.

Lewis states that the pirates disappeared but returned four months later and built a small hideaway at a place in the Lynn Woods called Pirate’s Glen, where they built a hut, made a garden, and dug a well. The pirates hid out there for a while until they were discovered by authorities, and three of them were arrested and sent back to England.

Veale managed to evade the authorities and escaped to a cave at Dungeon Rock, about two miles north of Pirate’s Glen, where it is believed the pirates had previously buried their treasure.

Veale lived there for some time and even worked as a shoemaker and occasionally came to town to purchase goods and supplies. Then in 1658, the earthquake struck, and the mouth of the cave collapsed, trapping Veale forever.

Dungeon Rock in the 19th Century:

Where exactly Alonzo Lewis found out about this story is unclear since there isn’t any evidence of these events actually happening. According to author James Newhall, in his 1865 book The History of Lynn, he even confronted Lewis directly about the origins of his story, but Lewis refused to answer:

“Without any desire to obliterate the glowing impressions which a fond credulity loves to cherish, it seems a duty to inquire as to the foundation on which these stories rest. No recorded evidence has been discovered respecting the persons and transactions so circumstantially brought to view. Among the records of the various courts, which abound in allusions, at least, to matters of even the most trivial significance, nothing is found. And none of the gossiping old writers who delighted especially to dwell upon whatever partook of the wonderful and mysterious make any mention of these things. The alleged abode of the pirates was almost within a stone’s throw of the Iron Works, which were in operation at the time; and yet we find no evidence that any about the Works even suspected the neighborhood of the outlaws. I once directly questioned Mr. Lewis as to whence he obtained the information; but he declined answering. It has, however, been understood that he simply claimed the authority of tradition; and is said to have remarked that his inquiries on the subject were induced by the same sort of evidence that induced his inquiries concerning the Iron Works” [Newhall 245.]

Lewis’ book was published in 1829, and it sparked public interest in the cave and the possible riches buried there.

In the 1830s, two attempts were made to recover the treasure by placing kegs of powder at the opening of the cave and igniting them. The efforts failed, and the opening to the cave was destroyed.

In 1851, a spiritualist named Hiram Marble purchased the land where Dungeon Rock is located from the city of Lynn and began excavating it with his son Edwin on June 5. The two men began digging a tunnel into the rock by blasting it with dynamite and chipping away at it with hammers and chisels to try and access the cave.

Marble, a member of the Spiritualist Church in Charlton, claimed that he was receiving instructions from the ghosts of two of the pirates, Thomas Veale and Captain Harris, as to the whereabouts of the reported treasure buried in the cave.

Marble stated that he received his instructions on where to dig directly from the ghosts by writing the words “I wish Veale or Harris would tell what move to make next” on a piece of paper. He would then fold the paper multiple times, and then call a medium into the room to feel the piece of paper and then write the ghost’s response.

The excavation proved to be difficult, though, and actually went on for decades. In addition to the tunnel, Marble also built a number of structures at the site, such as two-story house to live in as well as a tool shed, a powder storage structure, a blast wall, and a guest house that was never completed.

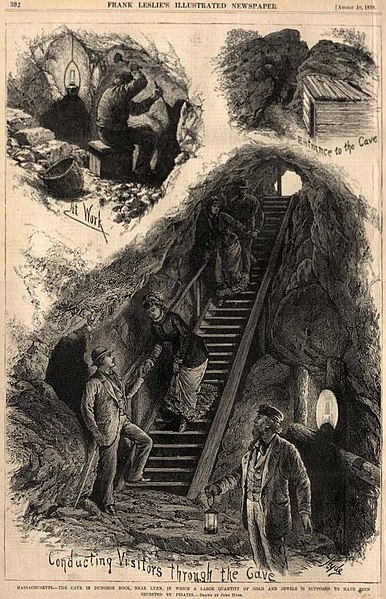

After only a few years, Marble’s savings of $1,500 was depleted, and he opened the site up to visitors as a tourist attraction, called Pirate’s Glen, to raise funds for the excavation. Marble charged a quarter for tours and also sold bonds for a dollar with the promise of a share of the treasure to investors.

In 1853, Hiram Marble uncovered a cutlass, a type of short-bladed sword, buried nearly 50 feet into the tunnel.

In September of 1855, Edwin broke his arm, between his wrist and his elbow, along with two fingers on his right hand, when the dynamite he was using detonated prematurely. His face and neck were also badly cut up and bruised.

In 1859, the Bradford Reporter newspaper reported that the Marbles had successfully excavated 100 feet into the rock and the last blast had developed a fissure in the rock, which leaked a foul-smelling air. The article also reported that Marble believed he had less than 10 feet to go until he reached the cave.

In 1861, Alonzo Lewis died, and Marble claimed he contacted him through a medium and received words of approval and encouragement from him, which Newhall pointed out as odd seeing that Lewis clearly stated in his book that he was against the idea of anyone excavating Dungeon Rock.

In March of 1862, the Boston Post reported that Marble said he found indications that he was close to reaching the cave and would soon discover the buried treasure. The article bluntly stated, “We shall believe it when he shall have found it.”

By 1863, the tunnel Marble was excavating was 135 feet long and was seven feet wide and the height of an average person. The opening to the tunnel was created to the immediate right of the collapsed entrance to the cave, and Marble’s plan was to dig a tunnel parallel to the cave and then turn left and dig into the cave from the side.

For some reason, Marble didn’t do this at all and instead veered the tunnel away in the opposite direction of the cave. He stated that the ghosts told him to do this for reasons they didn’t explain, as can be seen in a message he claimed he received from the ghost of Tom Veale through a medium:

“My dear charge, You solicit me or Captain Harris to advise you as to what to next do….As to the course, you are in the right direction, at present. You have one more curve to make, before you take the course that leads to the cave. We have a reason for keeping you from entering the cave at once. Moses was by the Lord kept forty years in a circuitous route, ere he had sight of that land which flowed with milk and honey. God had his purpose in doing so, notwithstanding he might have led Moses into the promise in a very few days from the start. But no; God wanted to develop a truth, and no faster than the minds of the people were prepared to receive it. Cheer up, Marble; we are with you, and doing all we can. Your guide, Tom Veale” [Newhall 247.]

In August of 1866, the Public Ledger newspaper reported that the tunnel was now 140 feet long but that “Mr. Marble will probably turn out a blasted old fool.”

In June of 1868, the Essex Institute held their annual Field Meeting in Saugus, and some members of the institute visited Dungeon Rock, where they met with Edwin Marble and learned about the excavation.

Edwin Marble told the institute members how he and his father conducted work on the excavation in the winter after earning enough money from visitors each summer, and they received instructions on which way to dig each winter through spiritual mediums.

In May of 1868, the Reading Eagle reported that the “deluded Marble is still blasting out Dungeon Rock…” and that the “misguidance of the spirits has changed his direction twenty times within the past year.”

Hirham Marble continued to dig the tunnel until he passed away on November 10, 1868, at the age of 65, without ever finding the treasure, and was buried at Bay Path Cemetery in Charlton, Mass.

In 1870, a man named Walter S. Jones was arrested and charged with assault and battery against Edwin Marble at Dungeon Rock but was later acquitted. It is not clear what the altercation was about.

In 1872, visitors to Dungeon Rock met with Edwin’s wife, her husband being absent at the time, and she reportedly showed them a pair of rusty scissors, part of a sword scabbard, and an old dagger with engravings on the blade, which she said were found in a seam in the rock deep inside the tunnel.

Edwin continued the excavation at Dungeon Rock, and the Boston Globe reported in 1876 that Edwin dug an additional nine feet into the tunnel that winter.

In 1878, the Boston Globe reported that although Edwin Marble claimed the spirits were guiding him in his work, he said the spirit of Tom Veale told him three years ago that he would not guide him any longer and that he now has to rely on his own intuition.

Edwin’s health eventually began to fade, as he was reportedly suffering from pulmonary issues and a “lack of enthusiasm,” and he struggled to keep up with his work, according to news reports in the Evening Standard and the Boston Transcript in 1879.

The tunnel became so deep at this point that large amounts of water began to accumulate at the bottom of the tunnel after each storm, which Edwin had to carry out by hand, sometimes up to 150 pails a day.

Nonetheless, Edwin continued the work until his own death on January 16, 1880, at age 49, reportedly from a “stroke of paralysis,” although the Portland Daily Press reported that he died of consumption, which he contracted while digging the tunnel. The Boston Transcript stated that Edwin “leaves no one, however, to continue the task of tunneling, and the ‘treasure’ still remains unrevealed.”

Since Edwin’s final wish was to be buried at Dungeon Rock, a grave was dug for him next to the rock, and a large pink rock was placed there to mark his grave.

After Edwin’s death, rumors apparently began to spread that Edwin had regretted his life’s work and no longer believed in the legend towards the end of his life.

In July of 1880, Edwin’s widow attempted to set the record straight when she told the Boston Globe that this was not true and that her husband never felt he was mistaken about the cave or the legend of buried treasure.

In 1881, the city purchased the land where Dungeon Rock is located and made it a part of a newly formed 2,200-acre park called Lynn Woods Reservation.

In 1882, Edwin’s widow was reportedly still living at her house near Dungeon Rock and was still a practicing spiritualist. She believed that the cave still held treasure and was actively looking for someone to continue the excavation.

In the 1880s and 90s, various groups and public speakers began holding speeches and events at Dungeon Rock, such as a spiritualist celebration in 1883, a political lecture by French journalist L.F. Massena in 1884, a concert by the C. N. Barker Concert Company in 1886, and a religious meeting and concert in 1890.

Dungeon Rock in the 20th Century:

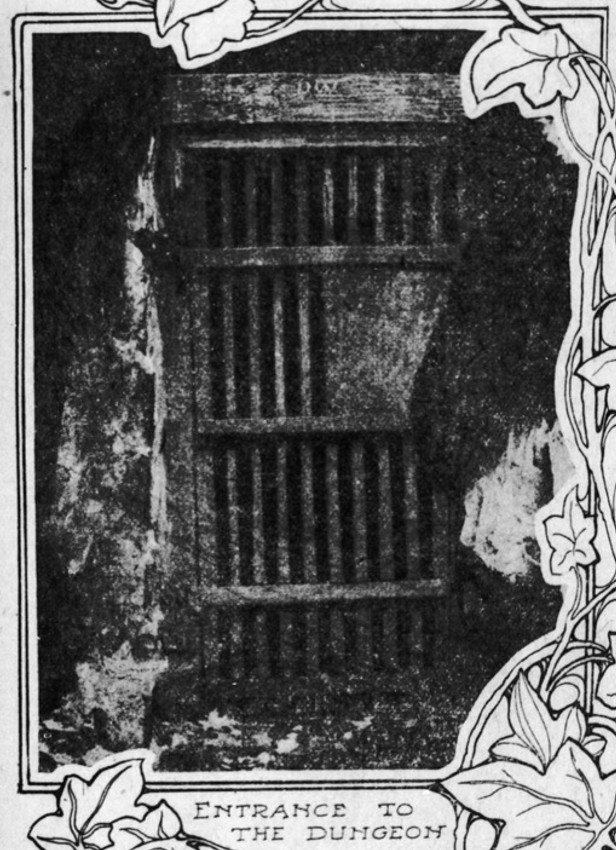

In the summer of 1925, the parks department unlocked the iron gate at the entrance of the tunnel and opened it to the public.

During the 20th century, the cave and stories of pirate gold often attracted young children and teenagers seeking adventure.

In 1932, two teenagers looted a store in Lynn of its cash and tobacco and hid out at Dungeon Rock while their parents looked for them. A third accomplice stole the loot they hid at Dungeon Rock, and the boys were eventually captured.

In 1938, three boys were rescued by firefighters after a group of older boys set fire to the entrance of the cave and trapped them in there.

In 1948, a 12-year-old boy suffered second-degree burns when he doused a cattail with lighter fluid and set it on fire so he could see inside the tunnel while hunting for the pirate treasure.

In 1956, six children were sealed inside the tunnel with rocks by a group of teenage boys and were only discovered by accident when police were called to the area due to reports of a wildfire and heard the children screaming in the tunnel.

The 174-foot-long tunnel still exists and is still guarded at night by an iron gate. The gate and tunnel are open to visitors Tuesday through Saturday from 9:00am to 2:30pm.

Sources:

“Dungeon Rock Still Hiding Pirate Gold to Be Reopened.” The Boston Herald, 6 Sept. 1925, p. 39.

“Police Free Six Children Sealed in Lynn Cave.” The Boston Globe, 14 Nov. 1956, p. 1.

“Aids Companions Trapped by Fire.” The Boston Globe, 5 June. 1938, p. 16.

“Pirates Peril Treasure Hunt.” The Boston Herald, 5 June. 1938, p. 1.

“Lynn Boy Burned Hunting Treasure in Dungeon Rock.” The Boston Globe, 18 Aug. 1948, p. 11.

“Mystery Flier Routs Pirate Gold Seekers.” The Boston Record, 18 Aug. 1948, p. 2.

“Older Boys’ Youth Prank Endangers Lives.” The Boston Post, 5 June. 1938, p. 1.

“Boys Emulate Pirates of Old.” The Boston Post, 5 Dec. 1932, p. 2.

“Two Men Gave Lives for Fabled Hoard of Dungeon Rock.” The Boston American, 19 Nov. 1905, p. 25.

“Pirates Glen and Dungeon in the Lynn Woods.” The Boston Herald, 1 Mar. 1903, p. 48.

“Tom Veale’s Treasure.” The Boston Globe, 29 Sept. 1890, p. 1.

“At Dungeon Rock, Lynn.” The Boston Globe, 24 Aug. 1884. p.7.

“Dungeon Rock and the Spiritualists.” The Lynn Bee, 11 June. 1883, p. 1.

“Buzzings About Town.” The Lynn Bee, 29 May. 1886, p. 4.

“Letter From Lynn.” Salem Gazette, 17 Feb. 1882, p. 2.

“Short Notes.” The Boston Globe, 11 July. 1880, p. 2.

“Death of Edward D. Marble.” The Boston Traveler, 17 Jan. 1880, p.1.

“Recent Deaths.” The Boston Transcript, 17 Jan. 1880, p. 1.

“Another Captain Kidd.” The Northern Pacific Farmer, 12 Feb. 1880, p. 3.

“Thomas Veal, a Pirate, Hid Himself and His Treasures in a Cave at Dungeon Rock.” The Portland Daily Press, 31 Jan. 1880, p. 1.

“Personal Items.” New England Farmer, 24 Jan. 1880, p. 2.

“Letter from the City of “Soles.” Salem Register, 26 Jan. 1880, p. 2.

“Digging for Treasure at Dunegon Rock.” The Boston Globe, 22 June 1878, p. 4.

“Dungeon Rock.” The Danvers Mirror, 23 June. 1877, p. 2.

“The Suburbs. Lynn.” The Boston Globe, 10 June. 1876, p. 2.

“Edwin Marble, the owner of Dungeon Rock, at Lynn.” The Evening Standard, 7 May. 1879, p. 2.

“Mr. Marble of Lynn, Mass.” Bradford Reporter, 24 Nov. 1859, p. 2.

“Mr. Marble Has Been Blasting at Dungeon Rock, Lynn, Mass.” The Public Ledger, 15 Aug. 1866, p. 2.

“The Deluded Marble is Still Blasting Out Dungeon Rock.” The Reading Eagle, 25 May. 1868, p. 1.

“Essex Institute Field Meeting at Saugus.” Salem Register, 15 June. 1868, p. 2.

“Dungeon Rock, Lynn.” The Boston Post, 28 Mar. 1862, p. 4.

“Dungeon Rock – More Money for Digging.” The Bay State, 8 May. 1851, p. 2.

“Edwin Marble, the owner of Dungeon Rock at Lynn.” The Boston Transcript, 7 May. 1879, p. 8.

“Lynn Locals.” The Boston Herald, 19 May. 1870, p. 4.

“A Visit to Dungeon Rock.” The Boston Transcript, 15 June. 1872, p. 3.

“Dungeon Rock.” Boston Journal, 15 Jan. 1853, p. 2.

“Accident at Dungeon Rock.” The Bay State, 27 Sept. 1855, p. 2.

“Mr. Marble of Lynn , Mass.” The New York Times, 17 Nov. 1859, p. 8.

Lewis, Alonzo. History of Lynn. Boston: J.H. Eastburn, 1829.

Lewis, Alonzo and James R. Newhall. History of Lynn, Essex County, Massachusetts: Including Lynnfield, Saugus, Swampscott and Nahant. Boston: John L. Shorey, 1865.

Ames, Nathan. Pirates’ Glen and Dungeon Rock. Boston: Redding & Company, 1853.

“Lynn Woods Reservation.” City of Lynn, lynnma.gov/departments/lynnwoods.shtml

Very good account of this mysterious and intriguing episode of Saugus and Lynn history. I grew up in Saugus and am the president of the Saugus historical society. Dungeon Rock and Pirate’s Glen continue to fascinate people of all ages.

Hi Laura, thanks for the comment. The story of Dungeon Rock really is so fascinating. I really enjoyed researching it and writing about it. I was thinking how great it would be if someone continued excavating it to find out if the story of the treasure is true but then I realized that maybe it’s more interesting if it remains a mystery. By the way, thank you for the work you do with the historical society! It’s not an easy or glamorous job but it is so important!