On September 9, 1913, the Great Fire of 1913 took place at Salisbury Beach in Salisbury, Massachusetts. The fire started in a photography studio on Broadway before it spread and eventually destroyed over 125 buildings.

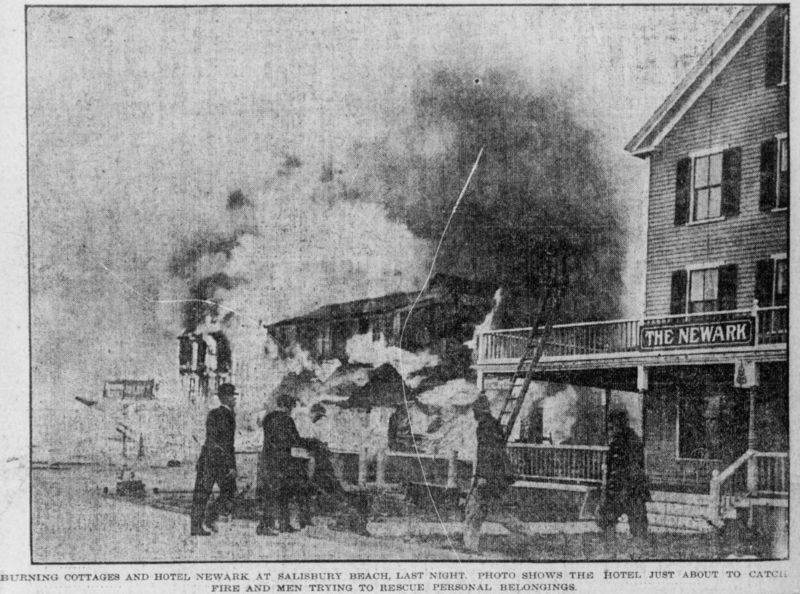

The majority of the buildings destroyed were located at the center of Salisbury Beach. They consisted of a church, six hotels, the post office, and around 100 beach cottages.

The fire started at 3:53pm in a photography studio owned by Arthur Williams, which was adjacent to the Cushing Hotel on Broadway, when either a stove became overheated or a lamp fell over – it’s not clear which – and a small fire spread to some inflammable materials and then ignited some flashlight powder, which caused a small explosion.

The fire then burst through the large skylight in the studio and swept through the bathhouses on top of the Cushing Hotel. It then spread from the hotel to several buildings across the street, the Rollaway and the Atlantic House.

The fire then jumped from the Atlantic House to a wooden dance hall, then to the stables at the rear of the building, some nearby cottages, and some stores and bathhouses.

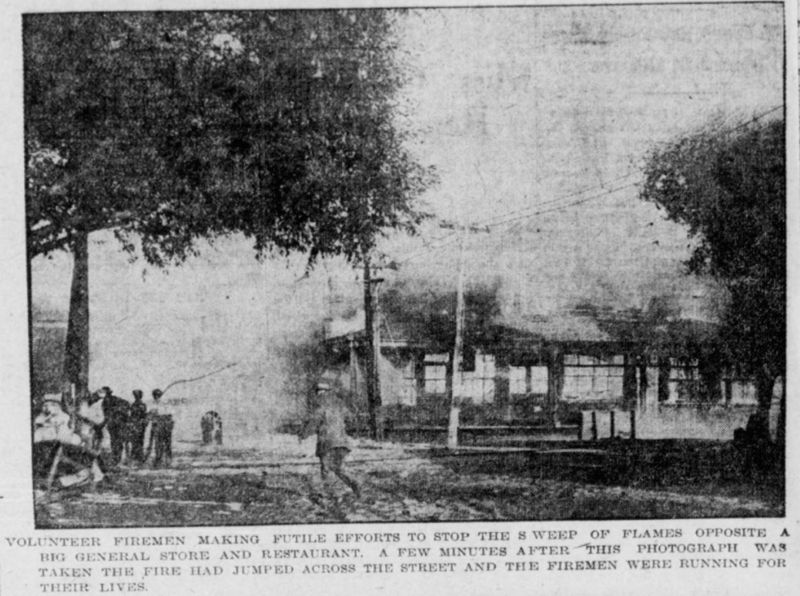

The fire continued to spread south for over a quarter of a mile as firefighters struggled to contain it due to a poor water supply, a lack of adequate fire equipment, and a persistent northeasterly wind that continuously fanned the flames.

The fire then burned the transfer station, several stores along the boardwalk, the Montgomery Dance Hall, which had been covered in wet raincoats, bedsheets, and overcoats to try and douse the flames, and some nearby cottages before it headed towards the north end section of the beach, where it continued to burn cottages along the beach.

The lack of water was so bad that four cases of beer were poured out onto the burning cottages in a desperate attempt to douse the flames, and a bucket brigade from the ocean was started to bring salt water to the flames.

“By this time everybody on the beach was trying in some way to fight the fire, but their efforts being disorganized proved fruitless,” according to a news report in the Boston Post.

Town officials then called the neighboring town of Newburyport to help fight the blaze. By the time they arrived, though, the entire midway was on fire.

Realizing how futile the situation was, they then called firefighters from Amesbury, Haverhill, and Portsmouth for help. The towns sent many fire engines, but there was no water for them at the beach to help douse the flames with.

The only way that firefighters were able to stop the spread of the fire was by dynamiting several cottages that were in the direct path of the blaze in the north end section of the beach in order to create a firebreak, according to a news report in the Boston Record:

“The use of dynamite was necessary to check the sweep of the flames, half a dozen cottages being removed by this means from the path of the fire for the protection of other dwellings. Other houses were pulled down for the same purpose, before the supply of dynamite had been secured.”

The wind soon died down, and the fire was finally extinguished after burning for a total of about five hours.

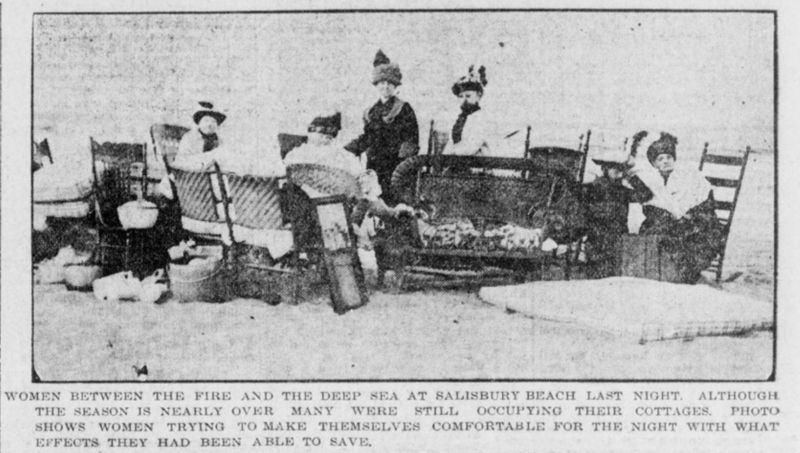

The fire left over 200 vacationers without a place to stay that evening, and many of them stayed up all night, shivering under whatever makeshift shelter they could find, guarding their piles of personal belongings that they rescued from the fire, according to a news report in the Pine Bluff Daily Graphic:

“Clad in thin clothing men, women and children had stood guard all night over the few belongings they were able to rescue from the sweep of the fires that devastated the summer resort. Heaps of smoking ruins were all that remained today of nearly 300 cottages and seven hotels that were in the path of the flames.”

Many of the other guests of the hotels and the nearby cottages destroyed in the fire lost all of their belongings. Food and water were in scarce supply after the fire, and vandals quickly began to loot the burned cottages.

Around midnight, a second fire broke out on the south end of Salisbury Beach and destroyed two cottages. The fire was suspected to be the result of arson.

A third fire also broke out nearby shortly after, and then a fourth fire broke out in the marsh, near the edge of the existing fire, but was extinguished fairly quickly. Firefighters on the scene said there was no doubt that it had been intentionally set in order to destroy the remaining nearby cottages.

A group of 24 armed citizens began guarding the fire-swept district of the beach to prevent looting or more potential arson attempts.

The following day, Police Chief Samuel Beckman said he believed the second fire was arson and expected to make an arrest in a matter of hours and even asked the state police for assistance. A squad of state police arrived at the beach that morning to investigate the possibility of arson. No arrests were ever made.

In the days following the fire, rumors began to swirl that the fires had been deliberately set in revenge against the Salisbury Beach Association, a realty trust that had recently purchased all of the beach land originally owned by the Salisbury Commoners, the original settlers, in 1911 to develop it for commercial use.

A legal battle over the land began the following year between the Commonwealth of Massachusetts and the Salisbury Beach Associates when the state seized much of the Associate’s beach property by eminent domain in order to create a state reservation.

The case went all the way to the Massachusetts Supreme Court, in a case known as the Salisbury Land and Improvement Company vs. Commonwealth, but the Associates ended up winning.

Shortly after, the Associates charged several people leasing cottages at the beach with trespassing when they refused to leave after the Associates demanded they buy their cottages at grossly inflated prices.

It was rumored that some of the cottagers had said that they “would rather burn their cottages than let the Associates have them,” which prompted the state police to investigate the remarks and the possibility of arson (Boston American 5.)

In late October, another fire broke out near the cottages again, and police believed it was again the result of arson set by a mysterious man seen leaving the scene of the fire in a carriage.

It seems that no evidence of arson or a revenge plot was ever proven, though, and it was determined that the fire was merely an accident, according to a news report in the Boston Record:

“Walter Coulson, one of the Salisbury Beach Associates, denied most emphatically that there had been any attempt to burn up the beach in revenge for the attitude taken by the Associates. To his knowledge, there had been no threats made, nor had he received a single threatening letter. He believed fully that the fire which started in the photography studio of Arthur Williams and which burned over 25 acres, destroying nearly 200 buildings, was entirely accidental.”

The notable buildings destroyed in the fire include the Cushing Hotel, the Atlantic House, Castle Mona, Hotel Leighton, the Newark Hotel, Hotel Comet, the Essex Block, the Phillips Bazaar, and several attractions, such as two dance halls and rides like the “Spiral Thrill” in the amusement park.

Fortunately, there were only a few minor injuries, and only one man was seriously hurt in the blaze. The man, Louis Blanchard of Amesbury, was a guest at the Cushing Hotel who jumped from a third-story window when the fire broke out. Blanchard was picked up unconscious, suffering from internal injuries and a few contusions, and taken to the hospital, where he was expected to make a recovery.

A clerk in the hotel, Joseph Daly of Lawrence, also fell down the stairs and suffered smoke inhalation when attempting to rescue the hotel owner’s daughter, who he believed was still trapped on the top floor but had already escaped.

The fire made national news and was reported in major newspapers across the country, including the New York Times and the San Francisco Call.

The estimated property loss caused by the fire was around $200,000. Parts of Salisbury Beach were later rebuilt, with the help of the Salisbury Beach Associates, but it was never the same after the fire.

Sources:

“Big Fire Sweeps Salisbury Beach.” New York Times, 10 Sept. 1913, p. 1.

“$300,000 Fire Sweeps Over Salisbury Beach.” The Boston Post, 10 Sept. 1913, p. 1.

“Salisbury Fire Not From Revenge.” The Boston Record, 11 Sept. 1913, p. 8.

“The Third Bad Fire.” Newburyport Daily News, 10 Sept. 1913, p. 8.

“Salisbury Beach is Swept by Big Fire.” The Pokeepsie Evening Enterprise, 10 Sept. 1913, p. 5.

“Summer Resort Guests are Routed by Fire.” Montgomery Advertiser (Alabama), 10 Sept. 1913, p. 1.

“Flames Eat Resort.” San Antonio Express, 10 Sept. 1913, p. 7.

“Summer Resort is Swept By Fire.” Pine Bluff Daily Graphic, 11 Sept. 1913, p. 7.

“Summer Resort Swept By Fire.” Clinton Daily Item, 10 Sept. 1913, p. 2.

“Salisbury Beach is Swept By Fire.” Salt Lake Telegram, 10 Sept. 1913, p. 1.

“Salisbury Beach Swept By Fire.” Meriden Record, 5 Sept. 1913, p. 56.

“Salisbury Beach Swept by Fire.” Lewiston Evening Journal, 8 Sept. 1913, p. 26.

“150 Cottages Burned.” Delaware City Press, 12 Sept. 1913, p. 1.

“Fire Eats Heart Out of Salisbury Beach.” Evening Times, 10 Sept. 1913, p. 16.

“Expect Arrest at Second Fire at Salisbury.” The Boston Record, 10 Sept. 1913, p.3.

“Fourth Fire Breaks Out at Salisbury Beach.” The Boston American, 10 Sept. 1913, p. 5.

“List of Cottages and Hotels Swept by Fire.” The Boston American, 10 Sept. 1913, p. 5.

“Lawrence Cottager in Court Fights Against Salisbury Associates.” Newburyport Morning Herald, 26 April. 1913, p.8.

“Think Fire at Salisbury Set.” The Boston Post, 26 Oct. 1913, p. 20.

“Vigilantes Guard Fire Zone.” The Pentwater News, 19 Sept. 1913, p. 7.

“Armed Men Guard Fire Swept Zone.” The San Francisco Call, 10 Sept. 1913, p. 3.

“Except Arrests Some Time Today.” Lewiston Evening Journal, 10 Sept. 1913, p. 25.

Callahan, Joe. “Today marks 100th anniversary of devastating Salisbury Beach fire.” Newburyport Daily News, 9 Sept. 2013, newburyportnews.com/news/local_news/article_897c9099-d07b-5c13-83aa-73e2bb3bf576.html