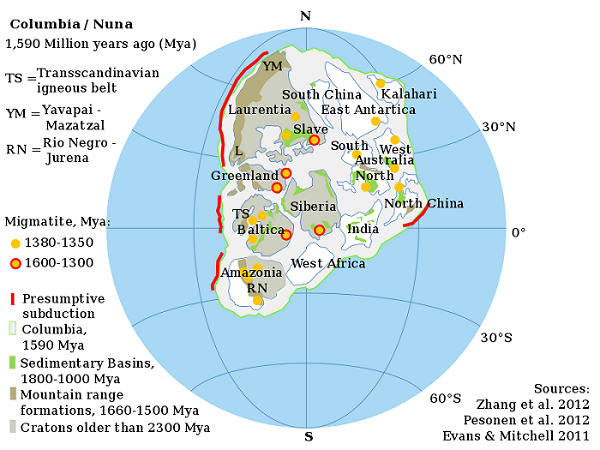

Approximately 2.5 billion years ago, the continent of North America was a part of an ancient supercontinent called Columbia.

Much of North America eventually broke off of Columbia and became a smaller continent called Laurentia.

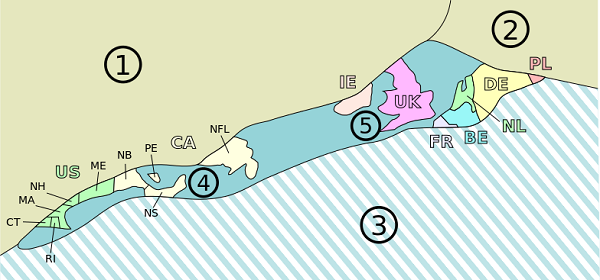

Laurentia later collided and merged with another continent called Avalonia, which was made up of land that New England now occupies, thus forming the continent of North America that we know today.

The Formation of North America:

Around 1.5 billion years ago, Columbia began to fragment and Laurentia and the other proto-cratons that made up the supercontinent broke off, and Laurentia became an independent continent.

Around 1.3 billion years ago, Laurentia became a part of a minor supercontinent called Protorodinia.

About 1.2 billion years ago, Laurentia became a part of a major supercontinent called Rodinia when it collided with other Mesoproterozoic continents.

Around 750 million years ago, Laurentia became a part of a minor supercontinent called Protolaurasia.

Around 600 million years ago, Laurentia was part of a major supercontinent called Pannotia. At that time, a warm, shallow sea covered most of Laurentia.

Around 565 million years ago, a microcontinent called Avalonia developed as a volcanic island arc after it broke off of a continent called Gondwana.

Avalonia was made up of what would later become the coastal area of New England, including Massachusetts, Connecticut, Maine, Rhode Island and New Hampshire, as well as sections of Nova Scotia in Canada and western Europe, including Ireland and the United Kingdom.

In the Cambrian era (541 to 485 million years ago ), Laurentia became an independent continent. Then, around 490 to 445 million years ago, continental drift moved Laurentia from the southern hemisphere into the sub-tropical latitudes, closer to the equator.

Meanwhile, around 450 million years ago, a volcano on Avalonia violently erupted, creating a caldera that eventually collapsed and eroded over millions of years, forming what is now the Great Blue Hill in Milton, Massachusetts.

In the Devonian period, between 416 to 358 million years ago, Laurentia collided against Baltica, forming a minor supercontinent called Euramerica.

Between 425 and 375 million years ago, all the major continents collided against each other, forming a major supercontinent called Pangaea. During this collision, Avalonia and Laurentia merged.

The collision also caused the formation of many of the tall mountains in New England, including Mt. Ascutney in Vermont, Mt. Greylock and Mt. Wachusett in Massachusetts and Mt. Monadnock in New Hampshire as well as the Berkshire hills in Massachusetts.

In the Jurassic era (201 – 145 million years ago), Pangaea broke off into two minor supercontinents: Laurasia and Gondwana. Laurentia and Avalonia were part of the minor supercontinent Laurasia.

During this process, rift valleys began to form within the interior of the continent of Laurasia. The Connecticut River Valley, located in what is now modern-day Vermont, western Massachusetts and Connecticut, is a failed rift valley that was formed during this time.

Geologic activity continued to shape the Connecticut valley region, causing frequent earthquakes and volcanic activity which eventually formed the Holyoke Mountain Range in Massachusetts.

Dinosaurs, such as Eubrontes, Gigandipus and Otozoum, also roamed the Connecticut River Valley during this time period but eventually went extinct about 65 million years ago.

In the Cretaceous period (145 – 66 million years ago), Laurasia split into two separate continents called Laurentia and Eurasia. Laurentia became the continent of North America and Eurasia became Europe and Asia.

In the Neogene period (23 – 2.6 million years ago) Laurentia crashed into South America, forming a minor supercontinent collectively called America (also known as the Americas).

Around 2.58 million years ago, the North American continent began experiencing the last ice age, known as the Quaternary glaciation, and much of the northeastern United States was covered in deep snow which compacted and formed into glaciers.

The Laurentide Ice Sheet:

Around 75,000 years ago, the Laurentide Ice Sheet formed, covering much of Canada and large portions of the northern United States.

As the ice sheet expanded, it advanced further and further south, eventually reaching New England around 25,000 years ago. Much of New England’s topography was formed during this period.

During the ice sheet’s migration south, it scraped off soil, gravel and sand from the surface of the land and pushed it out ahead of the front edge of the glacier, much like a plow.

Then, around 21,000 years ago, the climate began to warm right as the ice sheet reached just south of Cape Cod in Massachusetts.

This caused the ice sheet to melt and retreat, dropping its soil, sand and gravel deposits (called moraines) in the process along the north and south shores of Massachusetts, which created the peninsulas of Cape Cod and Cape Ann and the islands of Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket.

Yet, it should be noted that the land that the moraines sit on top of is much older than this and was created millions of years ago, according to a report by the Massachusetts Historical Commission on the Historical and Archaeological Resources of Cape Cod & the Islands:

“The formation of Cape Cod, Martha’s Vineyard, and Nantucket began over two million years ago. At that time, Cape Cod and the islands and a considerable expanse of land to the east and south stood well above sea level, forming the Continental shelf. Subsequently, the Ice Age (which actually included several glacial advances known as stages) with intervening interglacial periods were responsible for creating the land masses known today as Cape Cod and the Islands” (Massachusetts Historical Commission 7-8.)

The retreating glacier also dropped lighter material, rock dust and clay, that was then carried into the ocean by melting water. This rock dust and clay settled at the bottom of Boston harbor, forming a thick layer of Boston blue clay.

By about 16,000 years ago, the ice sheet had retreated so much that the Boston area was completely free of ice.

Sometime between 12,200 and 11,600 years ago, the ice sheet made a short readvance and pushed some of the Boston blue clay in Boston harbor into a low ridge, forming Boston neck, a small land bridge that once connected Boston to the mainland.

Around 12,000 years ago, after the ice sheet had fully retreated from the area, nomadic Paleoindian hunters, the first known inhabitants of Massachusetts, began moving into New England to hunt the ice age animals that lived in the region, such as ancient horses, mastodons, mammoths, dire wolves, giant beaver and camelops,

They mostly traveled in small bands of 10-15 people and frequently moved their camps to follow the herd of animals.

The oldest known Paleoindian site in the Northeast is located in Maine and dates back to 12,700 BP.

The New England that these Paeloindians inhabited was much different than the one we know today, according to an article in the Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society:

“New England was a vastly different place 12,000 years ago, when Paleo peoples made Wamsutta [an early Paleo site in Massachusetts] their wintering grounds. The retreating Laurentide Ice Sheet still had so much water locked up that the worldwide sea level was about 90 m (295 ft) lower than present; simultaneously land that had been depressed as much as 1,000 m (3,300 ft) by the immense weight of the Ice Sheet was rebounding. The result was startling differences from the continent we know today….A large part of Maine was then submerged; on the other hand, Nova Scotia (home of the Debert site) and the Grand Banks were islands. Massachusetts extended much further into the Atlantic Ocean that it does today; the islands of Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard were part of the mainland, Cape Cod was merely a feature of the terrain, and Wamsutta was well inland.” (Massachusetts Archaeological Society 54-55.)

By about 11,000 years ago, the ice sheet had continued to retreat and was just north of the St. Lawrence River in Canada.

According to an article in the American Antiquity journal, northern Maine at the time was a frozen tundra while Massachusetts was mostly forested:

“The tundra/forest boundary was located just below the ice patches near the Munsungan Lake area of Maine, with tundra encompassing almost the whole of the Canadian Maritime Peninsula, north and east of Maine, while northeastern Massachusetts was open coniferous/deciduous forest” (American Antiquity 426.)

After the ice sheet retreated it left behind many geological features such as drumlins (hills carved by glaciers), kettle holes (hollows dug by glacial ice), glacial erratics (non-native rocks carried by glaciers over great distances) as well as valleys and mountain passes known as notches.

The melting ice also released large amounts of water, creating many glacial lakes and kettle holes ponds across the state.

Some notable geological features created during the glacier’s retreat include:

Walden Pond in Concord, Massachusetts (a kettle hole pond)

Hathorne Hill in Danvers, Massachusetts (a glacial drumlin)

Bunker Hill in Charlestown, Massachusetts (a glacial drumlin)

Breed’s Hill in Charlestown, Massachusetts (a glacial drumlin)

Dorchester Heights in Boston, Massachusetts (a glacial drumlin)

Boston Harbor in Boston, Massachusetts (a depression carved by glaciers and later filled in by rising seas)

Boston Harbor islands in Boston, Massachusetts (glacial drumlins later submerged by rising seas)

Plymouth Rock in Plymouth, Massachusetts (a glacial erratic)

Babson’s boulders in Dogtown in Gloucester, Massachusetts (glacial erratics)

Dighton Rock in Berkley, Massachusetts (a glacial erratic)

Cape Ann, Cape Cod, Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard in Massachusetts (terminal moraines)

As the glaciers melted and the land rebounded from the weight of the heavy ice, the sea levels rose and the glacial drumlins in Boston harbor were submerged and became islands, according to an article on the National Parks Service website:

“The Boston Harbor Islands are a geological rarity, part of the only drumlin swarm in the United States that intersects a coastline. This ‘drowned’ cluster of about 30 of more than 200 drumlins in the Boston Basin are not all elongate in shape, as most other drumlins are (molded in the direction of glacial flow). Geologists believe the islands illustrate two separate periods of glacial action. Many of the islands have more than one drumlin.”

In addition, the moraines that made up Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard were also submerged and became islands, according to a report by the Massachusetts Historical Commission on Historical and Archaeological Resources of Cape Cod & the Islands:

“One of the most significant postglacial processes in the present configuration of Cape Cod and the Islands has been the continuously rising seas. For almost 70,000 years, present-day Cape and Islands were connected to the mainland, comprising during this time the interior highlands of the Continental Shelf. However, as a result of postglacial sea level increases, Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket sounds and Cape Cod Bay were filled, the now familiar bent armlike shape of the Cape took form, and the area was nearly severed from the mainland” (Massachusetts Historical Commission 19.)

Meanwhile, the rising sea levels flooded the coastal regions and the shoreline slowly receded to its present location, possibly submerging many early coastal archaeological sites in the process.

The large ice age animals that lived in the region eventually either moved north with the retreating glaciers or died out. By about 10,000 years ago, these animals became extinct possibly due to either human overhunting, climate change or both.

Around that time, different animals began to arrive in the area, such as caribou, moose, bear, elk and white tail deer, which the Paleoindians also hunted for food and clothing.

As the ice sheet continued to retreat and more land became habitable, the Paleoindians continued to explore and move about the region, establishing a handful of known Paleoindians sites across the state and many more across the Northeast.

During the Archaic period, starting around 9,000 years ago, the earth experienced the Holocene Climate Optimum, during which the climate warmed. The environment was still evolving and was hotter and drier that it is today.

By about 8,000 years ago, the vegetation became similar to what it is today and the forests that now cover New England were becoming more established, according to a report by the Massachusetts Historical Commission on the Historical & Archaeological Resources of Central Massachusetts:

“During the Middle Archaic period (ca. 8,000-ca . 6,500 B.P.) climatic and biotic changes continued, and by 8,000 B.P. The mixed deciduous forests of southern New England were becoming established, although changes in forest composition would continue throughout prehistory. By this time the present seasonal migratory patterns of many bird and fish species had become established and important coastal estuaries were developing” (Massachusetts Historical Commission 38.)

Also, around this time period, the population of people continues to grow and widespread populations of people in New England are present for the first time.

Sources:

“Historical and Archaeological Resources of Southeast Massachusetts.” Massachusetts Historical Commission, June. 1982, www.sec.state.ma.us/mhc/mhcpdf/regionalreports/SoutheasternMA.pdf

“Historical and Archaeological Resources of Central Massachusetts.” Massachusetts Historical Commission, Feb. 1985, www.sec.state.ma.us/mhc/mhcpdf/regionalreports/CentralMA.pdf

“Historical and Archaeological Resources of Cape Cod & the Islands.” Massachusetts Historical Commission, Aug. 1986, www.sec.state.ma.us/mhc/mhcpdf/regionalreports/capeandislands.pdf

“Historical and Archaeological Resources of the Boston Area.” Massachusetts Historical Commission, Jan. 1982, /www.sec.state.ma.us/mhc/mhcpdf/regionalreports/Bostonarea.pdf

“Historical and Archaeological Resources of the Connecticut River Valley.” Massachusetts Historical Commission, Feb. 1984, www.sec.state.ma.us/mhc/mhcpdf/regionalreports/CTValley.pdf

Robinson, Brian & Ort, Jennifer & Eldridge, William & Burke, Adrian & Pelletier, Bertrand. (2009). Paleoindian Aggregation and Social Context at Bull Brook. American Antiquity. 74. 423-447. 10.1017/S0002731600048691.

Chandler, Jim. “On the Shore of a Pleistocene Lake: The Wamsutta Site.” Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society, Vol. 62, No 2, pp: 52-62, 2001, maxwell.bridgew.edu/exhibits/BMAS/pdf/MAS-v62n02.pdf

“Geology and Formation of New England.” Memorial Hall Museum Online, www.memorialhall.mass.edu/classroom/curriculum_6th/lesson1/bkgdessay.html

Kopera, Joseph P. “The Bedrock Geology of Boston Harbor and Outer Harbor Islands.” National Park Service, www.nps.gov/boha/learn/management/research-abstracts-2011-kopera.htm

“Geological Formations – Boston Harbor Islands National Recreation Area.” NPS.gov, National Park Service, www.nps.gov/boha/learn/nature/geologicformations.htm

“Glaciers and Boston.” Boston Geology, bostongeology.com/boston/geology/islands/glaciers/glaciers.htm

“Glacial Origins of Cape Cod Presentation Recap.” Orleans Conservation Trust, orleansconservationtrust.org/glacial-origins-of-cape-cod-presentation-recap/

“Blue Hills: Archaeological Wonder of Epic Proportions.” Friends of the Great Blue Hills, friendsofthebluehills.org/keynote/

“Geology.” Center for Coastal Studies, coastalstudies.org/stellwagen-bank-national-marine-sanctuary/geology/

Fyon, Andy. “Marmora Ash Beds.” Ontario Beneath Our Feet, www.ontariobeneathourfeet.com/marmora-ash-beds

“Deglaciation of North America.” Museum of Archaeology & Ethnology, www.sfu.ca/archaeology/museum/exhibits/virtual-exhibits/glacial-and-post-glacial-archaeology-of-north-america/deglaciation-of-north-america.html

“Geological History of Jamestown, Rhode Island.” Jamestown, Rhode Island, www.jamestown-ri.info/avalonia.htm

Marshall, Michael. “The History of Ice on Earth.” New Scientist, 24 May. 2010, www.newscientist.com/article/dn18949-the-history-of-ice-on-earth/

“Cape Cod, Carved by Glaciers.” Live Science, 24 Nov. 2010, www.livescience.com/29842-cape-cod-carved-by-glaciers.html

Martin, Margaret. “Laurentide Glaciation of the Massachusetts Coast.” Emporia State University, academic.emporia.edu/aberjame/student/martin1/laurentide.html

“Glacial Cape Cod, Geological History of Cape Cod, Massachusetts.” USGS, pubs.usgs.gov/gip/capecod/glacial.html

This is very interesting. Thanks for your research and posting your findings. I’m a hiker and a blogger. In my travels, I have discovered that some of the parks and sanctuaries that I have hiked through were once volcanoes (i.e.Blue Hills) or mountains rivaling Mt. Everest (i.e. Wachusett Mountain.) Thanks again.

Can u tell us more about western mass and the ice sheets glaciers that came through? They say balance rock and whaconah falls windsor jams were all created from them.