Concord is a historic Massachusetts town in Middlesex County about 20 miles north west of Boston, Massachusetts. It was the first inland settlement in New England and in the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

The area was originally inhabited by the Pennacook Indians who named the area “Musketaquid,” which is an Algonquin word for “grassy plain.” The Pennacook population in the area was later decimated during a disease epidemic between 1616-1619.

Concord in the 17th Century:

Concord was settled by Reverend Peter Bulkeley, of Odell, England and Simon Willard, of Horsmonden, England, in 1636.

Under the direction of an early Massachusetts Bay Colony leader, William Spencer, Simon Willard began scouting locations for a new settlement for the colony sometime between 1634-35.

Around that same time, two minsters and religious dissenters in England, Reverend Peter Bulkeley and Revered John Jones were in trouble with the Church of England and decided to immigrated to the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

Official Seal of Concord Massachusetts

In 1634, Bulkeley sent some associates to the Massachusetts Bay Colony to prepare for his arrival, according to the First Parish of Concord website:

“Rev. Bulkeley had been ousted from his pulpit in Odell, England (where he had succeeded his father, Rev. Edward Bulkeley, in 1609), in 1634 after several warnings from Bishop Laud and the Church of England that he was not following the dictates of King Charles I. He, along with John Jones, knew full well that he would be removed from his pulpit sooner or later, so, being foresighted, he sent his oldest son Edward and a house builder named Thomas Dane to the colonies to build a house for Peter’s family. Rev. Bulkeley was a wealthy man, and fortunately for him, he was allowed to bring his money with him when he followed his son to the new world a year later. Rev. Jones might have had some wealth also, but he apparently was not permitted to bring it with him and arrived in the colonies with his family penniless, needing to seek immediate employment.”

According to the book The Bulkeley Genealogy, Bulkeley came to the New World specifically to escape the grasp of Archbishop Laud who had recently come to power and was determined to rid the church of non-conformist ministers like Bulkeley:

“The crisis came in 1634, when Mr. Bulkeley was suspended for non-attendance at the visitation of Sir Nathaniel Brent, Vicar-General. Afterwards he came and confessed that he never used the surplice nor the cross in baptism, ‘accounting them ceremonies, superstitions and dissentaneous to the holy Word of God. This of course meant that unless he admitted his error and showed a willingness to yield to the opinions of his ecclesiastic superiors, sooner or later he would lose his encumbency. Feeling a call to continue the preaching of the gospel, he decided to come to New England where he would be secure from the persecutions of Archbishop Laud. His case was allowed to drag, and it is possible that he secured delays through the influence of some of his highly-placed connections.”

Bulkeley left England and sailed to the New World aboard the ship the Susan & Ellen on May 9, 1635 and arrived in the colony in July or August of 1635. Bulkeley and Spencer decided on the area that is now Concord as the location for their new settlement.

The colonists petitioned the Massachusetts General Court for permission to settle there, according John Winthrop’s journal, History of New England:

“At this court there was granted to Mr. Bulkly and [blank] merchant, and about twelve families, to begin a town at Musketaquid, for which they were allowed six miles upon the river, and to be free from public charges three years; and it was named Concord. A town was also begun above the falls of Charles River.”

On September 12, 1635, the general court granted them permission to build a settlement there, stating:

“It is ordered that there shall be a plantation at Musketequid, and that there shall be six miles square to belong to it, and that the inhabitants thereof shall have three years immunities from all public charges except trainings. Further, that when any that shall plant there shall have occasion of carrying of goods thither, they shall repair to two of the next magistrates where the teams are, who shall have power for a year to press draughts at reasonable rates to be paid by the owners of the goods to transport their goods thither at seasonable times. And the name of the place is changed, and henceforth to be called Concord.”

Recruiting “undertakers,” or investors, and settlers for the settlement took place during the following winter of 1635-1636. One undertaker was Rachel Biggs of Boston who gave money in exchange for land grants in the settlement, although she never had plans to settle there herself.

Reverend John Jones and his family arrived in Boston in late October of 1635.

In the fall of 1635, a handful of early settlers arrived in Concord and built temporary homes for themselves and their cattle, according to the books, The History of Concord and Johnson’s Wonder-Working Providence.

It is not known exactly who the original twelve families were that were referenced in Bulkeley’s petition but some of the known settlers who came to Concord between 1635-1636 were:

Heywood

Heald

Fletcher

William and Thomas Bateman

Hosmer

Potter

Ball

Rice

Hartwell

Meriam

Judson

Griffin

George, Joseph and Obadiah Wheeler

John Scotchford

Each colonist was awarded a house lot and a portion of planting-ground and meadow land. Their cabins were located between what is now Concord square and Meriam’s Corner, according to the book The History of Concord:

“The first houses were thinly scattered from what is now Concord square to ‘Miriam’s corner.’ They were constructed by the driving or setting of upright stakes or logs at the foot of the hill, and the placing thereon of stringers or poles, which, resting on the sloping ground formed a roof admitting of a room beneath, by the removal of earth. The roof poles were covered with sods, or brushwood thatched with grass. The fireplaces were against the bank; and for light, the door may have served a partial purpose, supplemented by one or two small apertures, closing with sides or filled with oiled paper. It is stated that these structures were only designed for a temporary purpose, and made to the end that when kindly spring opened they could provide things more durable. It is said, however, that even the first winter Parson Bulkeley had provided for him a frame house.”

The land awarded to each colonist made up only a small portion of the whole land grant and the remainder was held in the common stock until the second land division in 1653.

Site of Major Simon Willard’s House, illustration published in The History of Concord Massachusetts, circa 1904

In 1636, the colonists officially purchased Concord from the Pennacook Indians. According to the book, The History of Concord, part of the price was paid in “wampum-peage, hatchets, hows, knives, cotton cloth, and shirts”:

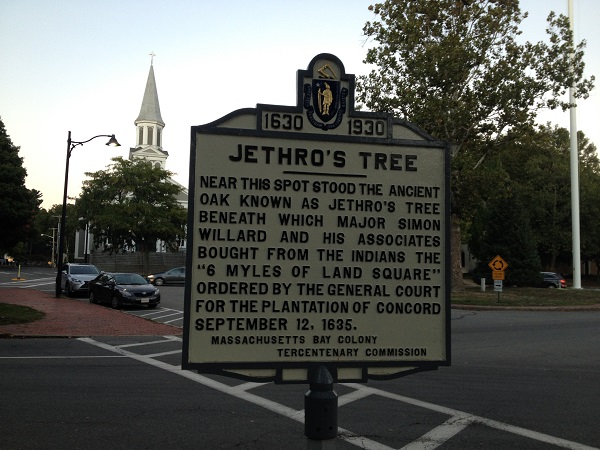

“The deed was early lost and never recovered, but there is ample evidence that it was duly executed and delivered. Tradition states that the bargain was made under an oak tree called Jethro’s tree, and that the tree stood at a spot just in front of the site of the old Middlesex hotel at the southwesterly end of Concord square.”

Jethro Tree Historical Marker, Concord, Mass. Photo credit: Rebecca Brooks

Yet, another tradition states that the deal was instead made at Peter Bulkeley’s house. A historical marker, located on Lowell road, marks the site of Bulkeley’s house and states that the deal took place there. The marker reads:

Here in the house of the Reverend Peter Bulkeley first minister and one of the founders of this town a bargain was made with the Squaw Sachem, the Sacamore Tahattawan and other Indians who then sold their right in the six miles square called Concord to the English planters and gave them peaceful possession of the land A. D. 1636.

On February 5, 1636, the settlers voted to build a meeting house on the hill that now overlooks Monument Square but the structure wasn’t actually built for at least a few years.

A burying ground, now known as the Old Hill Burying Ground, was later established nearby where the original settlers of Concord were eventually buried. Although it is not known exactly when the cemetery was established, the oldest headstone in the cemetery belongs to Joseph Merriam, who died April 20, 1677.

On July 5, 1636, Jones and Bulkeley came to Cambridge to officially “gather” their church at Concord, according to Winthrop:

“Mr. Bukly and Mr. Jones, two English ministers, appointed this day to gather a church at Newton [Cambridge], to settle at Concord. They sent word, three days before, to the governor and deputy, to desire their presence; but they took it in ill part, and thought not fit to go, because they had not come to them before, (as they ought to have done, and as others had done before,) to acquaint them with their purpose.”

More settlers came to Concord between the years 1636 and 1640:

Thomas Flint, from Matlock

William Hunt from Yorkshire

Ephraim Thomas from Wales

Timothy Wheeler, from Wales

Thomas Brooks from London

Jonathan Mitchell from Yorkshire

Other settlers who came during this time period were the families of Stow, Blood, Brown, Andrews, Atkinson, Barrett, Billings, Miles, Smeadley, Squire, Underwood, Burr, Draper, Farwell, Chandler, Gobble, Fox, Middlebrook, Odell and Fuller.

In April of 1637, the Concord settlers chose Reverend John Jones as their pastor and Reverend Peter Bulkeley as their teacher (a type of religious leader) and held a day of humiliation at Cambridge for their ordination.

On August 1, 1637, the settlers purchased more land from the Pennacooks. A record of the land sale reads as follows:

“Webb Cowet, Squa Sachem, Tahatawants, Natan quaticke alias Oldsman, Caato, alias Goodmans did express their consent to the sale of the weire at Concord over against the town & all the planting ground which hath been formerly planted by the Indians, to the inhabitants of Concord of which there was a writing, with their marks subscribed given into the court expressing the price given.”

In 1643, a number of Concord settlers, included Thomas Wheeler, felt that the best land in the town had already been awarded and decided to petition the court for a land grant in the northwest area of Concord. The land was awarded on the condition that they improved the grant within two years.

Around this time, a number of colonists began to express concerns that the soil was too poor to grow crops and stated that they found paying for two ministers too expensive (Massachusetts Bay colonists chipped in together to pay their minister’s salary which meant that the Concord colonists were paying twice what colonists in other settlements were paying.)

In 1644, the town’s pastor, Reverend John Jones, left Concord and went to the Connecticut River Valley, bringing nearly one eighth of Concord’s population with him, according to Edward Johnson in his book Johnson’s Wonder-Working Providence:

“This town was more populated once than now it is. Some faint-hearted souldiers among them fearing the land would prove barren, sold their possessions for little, and removed to a new plantation (which have most commonly a great prize set on them). The number of families at present are about 50. Their buildings are conveniently placed chiefly in one straite streame [streete] under a sunny banke in a low levell, their heard of great cattell are about 300. The church of christ here consists of about seventy soules, their teaching elders were Mr. Buckly, and Mr. Jones, who removed from them with that part of the people, who went away, so that onely the reverend grave and godly Mr. Buckly remaines.”

The colonists who followed Jones to Connecticut were:

Thomas Doggett

John Evarts

Jonathan Mitchell

William Odell

John Barron

John Tompkins

Benjamin Turney

Joseph Middlebrook

James Bennett

William Coslin (or Costin)

Ephraim Wheeler

Thomas Wheeler

The dwindling population in Concord prompted the Massachusetts Bay Colony government to prohibit anymore colonists from these settlements to leave without permission, according to this document from August 12, 1645:

“In regard of the great danger yt Concord, Sudberry, & Dedham will be exposed unto, being inland townes & but thinly peopled, it is ordered that no man inhabiting & settled in any said towns (whether married or single) shall remove to any other towne without the allowance of a magistrate, or other selectmen of that towne, until it shall please God to settle peace againe, or some other way of safety to the said townes, whereupon this court, or the councill of the common weale, shall set the inhabitants of the said townes at their former liberty.”

In 1651, the Concord Indians, led by their Sachem, Tahattawan, who was an early Christian convert, asked for and was granted a parcel of land to establish an Indian village which they named Nashoba.

The Indian village bordered Concord, in an area that is now Littleton, and the inhabitants became “Praying Indians,” meaning they converted to Christianity.

In 1654, Concord was divided into three quarters, which were referred to as the North, South and East quarters.

The North quarter contained the land north of the Concord River to the Assabet River, including most of the area around Concord junction. The settlers who lived in this quarter were the families of: Heald, Barrett, Temple, Jones, Brown, Hunt, Buttrick, Flint, Blood, Smedley and Bateman.

The South quarter contained the land south and southwest of Mill brook to the southern line of the North Quarter. The settlers who lived in the quarter were the families of: Luke Potter, George Heyward, Mikal Wood, Thomas Dane, Simon Willard, Robert Meriam, Thomas Brooks, Thomas Wheeler, James Blood, George Wheeler, Thomas Bateman and John Smedley.

The East quarter contained the land just eastward from the center of Concord toward what is now Lexington and the Concord River. The settlers who lived in this quarter were the families of: Ensign Wheeler, Fletcher, John Adams, Richard Rice, Robert and Greg Meriam, Thomas Brooke, Henry Farwell.

Up until this time, the only way to reach Concord was by what is now Virginia road. Many historians believe Virginia road was laid out by some of the original settlers of the town during scouting trips to the area prior to settling there in 1635.

In the 1640s and 50s, the settlers began building more roads in and around the town. Each quarter of the town was responsible for building and maintaining the roads in that quarter.

Some of the roads built during this time period were: the Woburn road in the East quarter, the Watertown road in the South quarter, the Sudbury road in the South quarter, the Billerica road in the North quarter, as well as the “old Marbloro road” and a road to Lancaster.

Historians speculate these roads were possibly built to help establish Concord as a fording or fishing center or to connect the settlement to a major transportation route or junction.

In 1654, a second land division was made and it was enacted that “all poor men of the town that have not commons to the number of four shall be allowed so many as amounts to four with what they all ready shall have till they are able to purchase for themselves and we mean those poor men that at present are householders.”

Around 1660, Sergeant William Buss established a tavern on Main Street.

In 1666, John Heywood also ran a tavern, called Black Horse Tavern, on what is now Main street.

In 1667, a new meeting house was built “to stand between the present house and Deacon Jarvis.” The meeting house was finally completed in 1681.

Since the meeting house had no heat, the parishioners kept their feet warm with wolf skin bags that were attached to the pews or benches and also brought dogs to church and rested their feet on or under the dog. Eventually dogs were prohibited in the church.

In 1675, King Philip’s war began and a number of Concord residents went off to fight in the war. The following is a partial list of Concord soldiers who fought in the war:

William Barrett Lt

James Wheeler

Richard Taylor

Moses Wheate

Richard Woods

John Melvin

Thomas Adams

Joseph Bateman

Hopewell Davis

John Bateman

William Ball

Samuel Fletcher Sr

Samuel Fletcher Jr

Paul Fletcher

Eleazer Brown

Moses Wheate

Stephen Gobble

Richard Pasmore (or Hosmer)

John Wood

Josiah Wheeler

Hugh Taylor

Eleazer Ball

John Potter

Daniel Adams

Simon Willard

Benjamin Graves

William Jones

Humphrey Barrett

John Barrett

William Hartwell

John Heale

James Smedley

Josiah Wheeler

Daniel Adams

John Bateman

On February 12, 1675, the “Massacre at Concord Village” occurred, during which a band of Indian warriors fighting in the war raided the area then known as Concord Village, which is now Littleton, and killed two men and captured a girl.

As warring bands of Indians began to sweep New England, the Praying Indians at Nashoba were rounded up and brought to Concord where they were placed in the custody of John Hoar, according to the History of Concord Massachusetts:

“At Concord they were placed in charge of John Hoar, their unfailing friend, the only man in town it is said who was willing to receive them. Standing up stoutly against a strong public sentiment, for the tragic affair at Brookfield [the Siege of Brookfield] and other Indian atrocities which it was suspected some of the praying Indians had sympathy with were still recent, Mr. Hoar acted as a protector, erecting for them a building where they could be secure from all indignities whether from within or without the town, and providing employment by which they could earn a living.”

The building Hoar built for them was a workhouse, in which they were locked up at night. That didn’t seem to reassure the other settlers that these Indians were not a threat though, according to the book A History of the Town of Concord, Middlesex County, Massachusetts:

“The number of those Indians was about 58 of all sorts, whereof were not above 12 able men, the rest were women and children. These Indians lived very soberly and quietly and industriously and were all unarmed, neither could any of them be charged with any unfaithfulness to the English interest. In pursuance of this settlement, Mr. Hoar had begun to build a large and convenient work-house for the Indians, near his own dwelling, which stood about the midst of the town, and very nigh the town watch-house. This house was made, not only to secure those Indians under lock and key by night, but to imploy them and set them to work by day, whereby they earned their own bread; and in an ordinary way (with God’s blessing) would have lived well in a short time. But some of the inhabitants of the town, being influenced with a spirit of animosity and distaste against all Indians, disrelished this settlement, and therefore privately sent to a captain of the army [probably Capt. Mosely], that quartered his company not far off at that time…This captain accordingly came to Concord with a party of his men upon the Sabbath day into the meeting-house, where the people were convened in the worship of God. And after the exercise was ended, he spake openly to the congregation to this effect ‘that he understood, there were some heathen in the town committed to one Hoar, which, he was informed, were a trouble of and disquiet to them; therefore if they desired it he would remove them to Boston.’ To which speech of his, most of the people being silent, except two or three that encouraged him, he took, as it seems, the silence of the rest for consent, and immediately after the assembly were dismissed, he went with three or four files of men, and a hundred or two of the people, men, women, and children at their heals, and marched away to Mr. Hoar’s house: and there demanded of him to see the Indians under his care. Hoar opened the door and showed them to him, and they were all numbered and found there. The captain then said to Mr. Hoar, that he would have a corporal and soldiers to secure them; but Mr. Hoar answered there was no need of that for, they were already secured, and were committed to him by order of the Council, and he would keep them secure. But yet the captain left his corporal and soldiers there, who were abusive enough to the poor Indians by ill language. The next morning the captain came again to take the Indians, and send them to Boston. But Mr. Hoar refused to deliver them unless he showed an order of the Council; but the captain could show him no other but his commission to kill and destroy the enemy. Mr. Hoar said these were friends and under order; but the captain would not be satisfied with his answer, but commanded his corporal forthwith to break open the door, and take the Indians all away, which was done accordingly; and some of the soldiers plundered the poor creatures of their shirts, shoes, dishes, and such other things as they could lay their hands upon, though the captain commanded the contrary. They were all brought to Charlestown with a guard of twenty men….To conclude this matter, those poor Indians, about 58 of them of all sorts, were sent down to Deer Island, there to pass into the furnace of affliction with their brethern and countrymen.”

Only about twelve of the Nashoba Indians sent to Deer Island ever returned to Concord.

King Philip’s War came to an end in 1676. A total of 16 Concord soldiers were killed in the war. The following is a partial list of those killed:

Samuel Smedley, was one of eight who fell at the swamp fight during the Siege of Brookfield in 1675

Henry Young, shot at the Brookfield garrison while looking from a window during the Siege of Brookfield in 1675

George Hayward, killed at the swamp fight in the Narrangansett Expedition in 1675

James Hosmer, killed at the Battle of Sudbury in 1676

Samuel Potter, killed at the Battle of Sudbury in 1676

David Comy, killed at the Battle of Sudbury in 1676

John Barnes, killed at the Battle of Sudbury in 1676

In 1684, the Massachusetts Bay Colony’s charter was revoked due to violation of several terms of the charter. This sent the colonists into a state of panic and the future of the colony and its legal standing became unclear.

Hoping to make their claim on Concord more legal, the colonists tried to find the original land deed that they made with the Indians but discovered that it was lost.

In its place, many of the colonists gave sworn dispositions in a court of law stating that they purchased the land from the Indians in 1636:

“The testimony of Richard Rice aged seventy-two years sheweth that about the year one thousand six hundred thirty six there was an agreement made by some undertakers for the town since called Concord with some Indians that had right unto the land then purchased for the township. The indians was Squaw Sachem, Tohutawun Sagamore, Mattunkatucka, and some other Indians ye lived then at that place, the tract of land being six square miles, the center of the place being about the place the meeting house standeth now, the bargain was made & confirmed between ye English undertakers & the Indians then present., to their good satisfaction on all hands. 7.8.84 Sworn in court, Tho Danforth record.”

A member of the Pennacook tribe even gave testimony of this land deal:

“The deposition Jehojakin alias Mantatucket a christian Indian of Natick aged 70 years or therebouts, this deponent testifyeth & sayth, that about 50 years since he lived within the bounds of that place which is now called Concord at the foot of an hill named Nawshawtick now in the possession of Mr Henery Woodis & that he was present at a bargain made at the house of Mr Peter Bulkeley (now Captain Timothy Wheeler’s – between Mr Simon Willard Mr John Jones, Mr Spencer & several others in behalf of the Englishmen who were settling upon the said town of Concord & Squaw Sachem, Tahuttawun & Nimrod Indians which said Indians (according to ye particular rights & interests) then sold a tract of land containing six mile square – the said house being accounted about the center) to the said English for a place to settle a town in. And he the said deponent saw said Willard & Spencer pay a parcell?? of wompompeag, hatchets, hows, knives, cotton cloth & shirts to the said Indians for the tract of land: and in particular he the said deponant perfectly remembereth that Wompachowet husband to Squaw-Sachem received a suit of cotton cloth, an hat, a white linen band, shoes, stockings & a great coat upon account of said bargain. And in the conclusion the said Indians declared themselves satisfied & told the Englishmen they were welcome. There were also present at the said bargain waban, merch thomas his brother in law Nowtoquatuckquaw an Indian, Antonuish now called Jethrotaken upon oath 20th October 1684”

In 1686, King James II created the Dominion of New England, which merged the colonies of Massachusetts Bay, Connecticut, New Hampshire and Rhode Island together and created a royal government in an attempt to gain more control over the colonies. The dominion was highly unpopular and the colonists resented the king for taking away their power to self govern.

In 1688, the Glorious Revolution of England occurred, during which King James II was overthrown by his daughter Mary and her husband William of Orange.

When the news reached the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1689, talk of a revolt against the dominion officials began to spread.

On April 18, 1689, the Boston Revolt of 1689 began, during which the dominion was overthrown.

In response to the uprising, Lieutenant John Heald, of Concord, mustered the town’s military company the following day and headed to Boston to assist in the revolt.

This was the first of three times that Concord’s militia marched into battle on April 19 in the interest of American democracy, according to the book The History of Concord Massachusetts:

“It is a notable fact that three times upon the 19th of April with about a century between each, the town’s militia have marched forth in the interest of American democracy. The first in 1689, to assert it, the second in 1775 to create it, and the third in 1861, to protect it.”

When the governor of the dominion, Sir Edmund Andros, was captured during the Boston Revolt and the order was issued to remove him for safe keeping until he could be sent back to England, it was Concord resident and Clerk of Representatives, Ebenezer Prout who signed the order.

On May 22, 1689 the town held a meeting and voted to reinstate the former Puritan-run government and awaited orders from the new monarchs, Mary and William of Orange.

In 1691, the new monarchs decided against reinstating the original charter and instead issued a new charter which further restricted the colonist’s ability to self-govern and forbade many of their former religious based-laws.

Around 1697, the South Burying Place, now known as Main Street Burying Ground, was established. The site now contains around 300 graves. The oldest headstone dates back to 1697 and the cemetery also contains the graves of 13 Revolutionary War soldiers.

Concord in the 18th Century:

In 1710, the town built a new meetinghouse which still stands today.

In 1719, the town built a new structure for its town meetings and court sessions, which had previously been housed in the meeting house.

This structure came to be known as the First Parish Meeting house and it went on to host many important events such as a meeting of the First Provincial Congress in 1774 and the Second Provincial Congress in 1775 and in 1776 the commencement exercises of Harvard College were held there.

First Parish Meeting-house, 1712, from an old sketch made on a pine board, published in The History of Concord Massachusetts, circa 1904

In 1770, Reverend William Emerson built the Old Manse, a Georgian-style mansion, near the Old North Bridge.

In 1774, Ephraim Jones built Wright’s Tavern on Main Street.

By 1775, Concord’s population reached 1,400.

On April 19, 1775, one of the first battles of the American Revolution took place in Concord. After Paul Revere, William Dawes and Samuel Prescott warned the countryside that British forces were approaching from Boston, the local militia gathered in Wright’s tavern to await the forces in the early morning hours.

When the troops arrived and began searching for the colonist’s hidden ammunition supplies at Col. James Barrett’s farm, about 400 hundred minutemen approached the troops guarding the Old North Bridge and engaged in a battle that later came to be known as the Battle of Concord.

The battle was kicked off by the famous Shot Heard Round the World and a total of three British soldiers were killed during the fight. Two of them were later buried at the Old North Bridge and another was buried at Monument square.

After being defeated in the battle, the British troops retreated back to Boston where they were then blockaded in by the militia, an event now known as the Siege of Boston.

During the siege, thousands of Boston residents fled the town out of fear for their safety. The Provincial Congress ordered nearby towns in Massachusetts to take in the refugees and Concord’s population soon swelled to 1,900 people as a result.

Some of these new residents were also students from Harvard. Since over 1,600 American soldiers assisting in the siege were being housed in Harvard University’s dormitories and other buildings in Cambridge, the university decided to relocate its classes to Concord in October of 1775.

Around 100 students boarded in various homes, taverns and residences in the town and attended classes in a deserted grammar school, in the local courthouse and in the First Parish Meetinghouse.

When the siege ended in March of 1776, the students eventually returned to Cambridge.

Concord in the 19th & 20th Century:

In the 19th century, the industrial revolution began to change the landscape and the buildings in Concord. Widespread deforestation of the Concord woods was rampant and new mills and factories began to sprout up.

In 1808, the Damon mill was built on the Assabet River at Pond Lane. The mill produced a unique textile known as domett cloth, a light wool-cotton flannel.

In 1817, Henry David Thoreau was born at the Minot farm House on Virginia Road.

In 1834, Ralph Waldo Emerson moved to Concord and lived in his ancestral home, the Old Manse. Due to Emerson’s literary influence, a number of notable authors soon followed Emerson to Concord, making it a literary hot spot in Massachusetts.

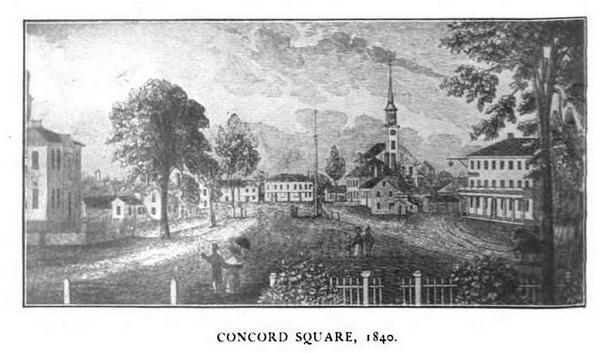

Concord Square, Concord, Mass, illustration published in the History of Concord Massachusetts

In 1840, The Alcott family, including young Louisa May Alcott, moved to Concord.

In 1842, Nathaniel Hawthorne moved to Concord with is new wife Sofia Peabody and rented the Old Manse from Emerson.

In 1823, Sleepy Hollow Cemetery was established on Bedford Street.

In 1842, the Fitchburg Railroad line from Boston to Fitchburg, Mass, was established and the section of track that passed through Concord, near Walden Pond, was built in 1844. A train station in Concord was also built at this time.

On April 30, 1844, Henry David Thoreau accidentally started a major forest fire that burned down half of the Concord woods. Concord residents were furious with Thoreau for causing the fire and began taunting him with calls of “burnt woods” and “woods burner” wherever he went.

On July 4, 1845, Thoreau moved into a small cabin at Walden pond and started his two year experiment in simple living, which later became the basis of his famous book Walden.

Concord became an important part of the abolitionist movement and a number of homes in the town, such as the Wayside and Orchard House, became stations on the Underground Railroad.

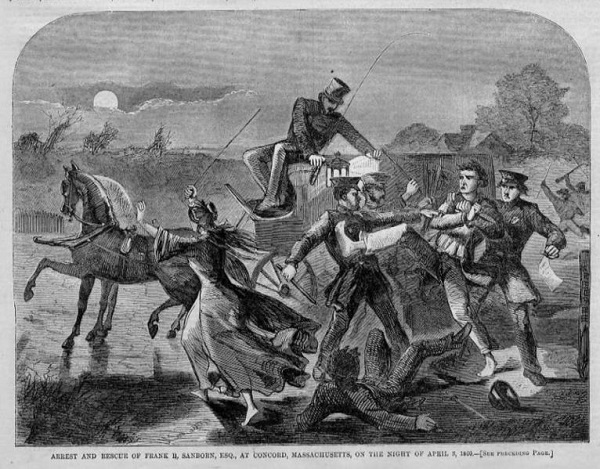

On the night of April 3, 1860, Federal marshals attempted to arrest Concord schoolmaster, Frank Sanborn, for his connection to abolitionist John Brown after Brown’s failed raid on Harper’s Ferry.

Frank Sanborn of Concord, MA, resists arrest by Federal Marshals in regard to his support of abolitionist John Brown, illustration published in Harper’s Weekly, circa 1860

Sanborn was one of the Secret Six, a group of business men who financed John Brown’s abolitionist activities. Sanborn was detained in Concord with plans to take him to Washington D.C. for questioning but was quickly released when over 150 Concord residents, including local judge Ebenezer Hoar, demanded the marshals free him.

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, a number of Concord residents joined the army and marched off to war.

The first Concord regiment to join the war effort was the Concord artillery who left for Washington D.C. on April 19, 1861.

The regiment served in the Battle of Bull Run on July 21, 1861 and was mustered out of service on July 31, 1861 after completing its required three month enlistment.

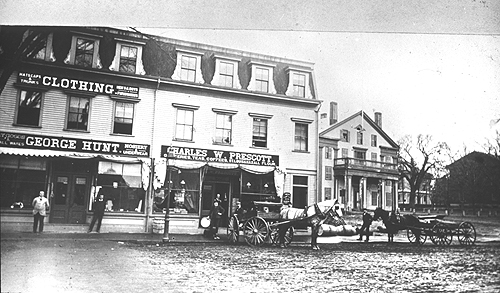

Concord Center, Concord, Massachusetts, circa 1865

In 1868, an amusement park named Lake Walden Amusement Park was established at Walden Pond. The park featured seesaws, swings, slides, a boathouse, a bathing house, and dance hall. The park burned down in 1902 and was never rebuilt.

On April 19, 1875, Concord held a centennial celebration for the Battle of Concord which President Ulysses S. Grant attended.

In 1887, the Concord Armory was built on Walden Street.

In 1894, the West Concord station for the MBTA railroad line was built on Commonwealth Ave in West Concord.

In 1904, the population of Concord had grown to 5,000 to 6,000 and has since grown to 17,669.

Monument Square in Concord, Mass, circa 1914

The town has since become a popular tourist destination for both history fans, nature lovers, and fans of the 19th century Concord writers and has become home to various historic house museums as well as the Concord Museum.

Sources:

Ireland, Corydon. “Harvard’s Year of Exile.” Harvard Gazette, 13 Oct. 2011, news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2011/10/harvards-year-of-exile/

“South Burying Place.” The Town of Concord, Massachusetts, www.concordnet.org/318/South-Burying-Place

“Old Hill Burying Ground.” Town of Concord, Massachusetts, www.concordnet.org/315/Old-Hill-Burying-Ground

Drake, Samuel Adams. History of Middlesex County, Massachusetts. Vol. 2, Estes and Lauriat, 1880.

Walcott, Charles Hosmer. Concord in the Colonial Period: Being a History of the Town of Concord. Estes and Lauriat, 1884.

Shattuck, Lemuel. History of the Town of Concord, Middlese County, Massachusetts. Russell, Odiorne, and Company, 1835.

Johnson, Edward. Johnson’s Wonder-working Providence, 1628-1651. Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1910.

The Bulkeley genealogy: Rev. Peter Bulkeley. Compiled by Donald Lines Jacobus, 1933.

Winthrop, John. History of New England, 1630-1649. Vol. 1, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1908.

Hinman, Royal Ralph. A Catalogue of the Names of the Early Puritan Settlers of the Colony of Connecticut. Press of Case, Tiffany and Company, 1852.

Genealogies of Some Old Families of Concord, Massachusetts. Vol. 1, Edited by Charles Edward Potter, Heritage Books, 2007.

Hudson, Alfred Sereno. The History of Concord, Massachusetts. The Erudite Press, 1904.

Crawford, Mary Caroline. Little Pilgrimages Among Old New England Inns. L.C. Page & Company, 1907.

Chapman, F.W. The Bulkeley family; or the descendants of Rev. Peter Bulkeley, who settled at Concord, Mass., in 1636. Higgins Book Company, 1989.

Bodge, George Madison. Soldiers in King Philip’s War: List of the Soldiers of Massachusetts Colony, Who Served in the Indian War of 1675-1677. Boston, printed for the author, 1891.

“The Soldiers and Sailors of Concord.” Internet Archive, archive.org/stream/soldierssailorso00conc/soldierssailorso00conc_djvu.txt

“Ministers of the First Parish Church in Concord: 369 Years of Parish Ministry.” First Parish Church, Feb. 2006, www.firstparish.org/ministers/

“History of Concord.” Concord Museum, www.concordmuseum.org/history-of-concord.php

Peter Bulkeley was my 10×great grandfather, and since he’s on a direct paternal line I have his Y chromosome.

Very nice summary of Concord’s early history. I am descendant of the Brooks and Meriam families, as well as a host of other Concord rebels.

John Hoar is my 9 Times Great grandfather. I am so proud of him. He was an attorney. He was on many town councils. He saw a problem and fixed it. Wonderful Concord stories

BEST WEBSITE EVER!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

I am direct descendant of William Odell who was with Rev. Bulkley on ship and arrived at Concord with dau. Rebecca, sons James (died young) and John. 1672 William removed to Fairfield.

Good day ,

My grandmother married Nehemiah Odell – NJ in 1932. His mother Rebecca Sears is a descendant of Major Simon Willard as well as Francis Blood : 1735-1814 ( Representative and Commissary during the Revolution. My mother told me stories of her Aunts being members of the DAR.

Regards,

Barbara

I’m a direct descendant of Major Simon Willard and find Concord’s history absolutely fascinating. As children, we would visit Concord on our way to Boston to see our grandparents during summer vacation. And this always meant recalling which books we’d studied during the school year and which writers’ home we should find. This enriched our studies and our fun immensely. Lovely memories!

Good day ,

I am also a relative to Major Simon Willard. His daughter Elizabeth married Robert Blood April 8 th 1653. And so , the Blood line began as well as many other surnames. I have traced the Willard family to Kent , England . I have dated back to my 14th x grandfather William Willard born 1470 Brenchley , Kent England. He married Johanna Downer in 1499 . The Willard’s were Saxon Thanes Free Retainers of an Anglo Saxon Lord.

With Kindest Regards,

Barbara

Thank you very much for this!

Major Simon Willard was my 10 th x grandfather and his wife was Elizabeth Blood Willard. I can trace my grandfathers family to 1220 .

Thank you for the wonderful article.

Regards,

Barbara

Very well written and understandable. I enjoyed it. It helped me more fully understand the process and problems of planting a new town. I had never heard of the Dominion of New England. Timothy Wheeler is my ancestor.

Thank you very much. William Hunt of Yorkshire was my ancestor.