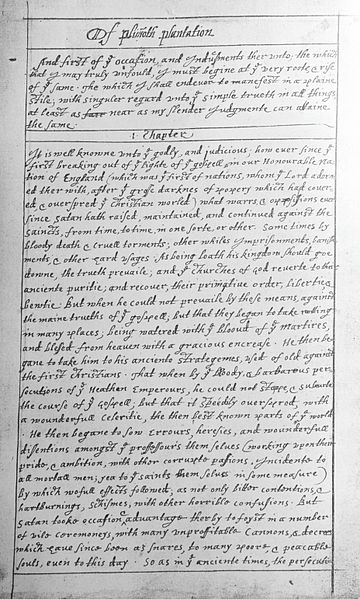

Mayflower pilgrim William Bradford wrote a detailed manuscript describing the pilgrim’s experiences in Holland and in the New World, which is now known as Of Plymouth Plantation.

In the manuscript, Bradford recorded everything from the pilgrim’s experiences living in the Netherlands, to their voyage on the Mayflower and their daily life in Plymouth colony.

The book is considered the first American history book ever written and is known by many names, such as The History of Plymouth Plantation, History of the Plantation at Plymouth and William Bradford’s Journal.

When Was Of Plimoth Plantation Written?

The book was written between the years 1630 and 1651, and is a 270 page manuscript written in the form of two books.

Why Was Of Plimoth Plantation Written?

William Bradford explains, in chapter six of the book, that the reason he wrote the manuscript was so that the descendants of the Pilgrims would know and appreciate the hardships their ancestors faced:

“I have been ye larger in these things, and so shall crave leave in some passages following, (though in other things I shall labour to be more contract,) that their children may see with what difficulties their fathers wrestled in going through these things in their first beginings, and how God brought them, along notwithstanding all their weakness and infirmities. As also that some use may be made hereof in after times by others in such like weighty employments; and herewith I will end this chapter.” (History of Plimoth Plantation p. 58).

Bradford never made any attempt to publish the manuscript during his lifetime and instead gave it to his son William, who later passed it on to his own son Major John Bradford.

A number of people borrowed the manuscript over the years, such as William Bradford’s nephew, Nathaniel Morton, who referenced it in his book New England’s Memorial in 1669, and later Reverend Thomas Prince, who used part of the manuscript in his own book Chronological History of New England in 1736.

According to editor William T. Davis, in the introduction to the 1908 edition of Bradford’s History of Plymouth Plantation, Prince then gave the manuscript to the New England Library:

“The manuscript bears a memorandum made by Rev. Thomas Prince, dated June 4, 1728, stating that he borrowed it from Major John Bradford, and deposited it, together with Bradford’s letter-book, in the New England Library in the tower of the Old South Church in Boston” (Bradford’s History of Plymouth Plantation p. 15)

During its time at the library, William Hubbard borrowed the manuscript and referenced it in his book History of New England, as did Thomas Hutchinson, who used it as a reference for his book History of Massachusetts Bay in 1767.

The Original Manuscript Goes Missing:

What happened next to the manuscript is unclear. At some point in the late 1700s, the manuscript disappeared. It remained missing for over half a century until it was discovered in the Bishop of London’s Library at Fulham in 1855.

It is not known exactly how the manuscript got there but Davis suggests Hutchinson may have brought it to England when he was using it for research:

“It is not improbable that it was in Hutchinson’s possession when, adhering to the crown, he left the country, and that in some way before his death in Brompton, near London, in June, 1780, it reached the Library of the Bishop of London at Fulham, where it was discovered in 1855.” (Bradford’s History of Plymouth Plantation p.16)

Other sources, such as an article in Life magazine in 1945, suggest the manuscript was instead stolen by British soldiers who occupied the Old South Church during the Siege of Boston:

“In 1856 [sic], the long-lost journal of Plymouth Colony’s Governor William Bradford unaccountably turned up in the private library of the Bishop of London. It had apparently been stolen from Boston’s Old South Church by British soldiers quartered there during the Revolution.”

According to editor Charles Deane, in the editorial preface of the 1856 edition of History of Plymouth Plantation, the location of the manuscript was discovered by Reverend John Barry, a historian working on the first volume of his book History of Massachusetts.

During his research, Barry found familiar passages in a book published in London in 1846, titled A History of the Protestant Episcopal Church in America by Samuel Lord Bishop of Oxford. The passages matched word-for-word to passages of Bradford’s manuscript cited in Morton’s book, according to Deane’s preface:

“On the 17th day of February, 1855, the Rev. John S. Barry, who was at that time engaged in writing the first volume of his History of Massachusetts, since published, called upon me, and stated that he believed he had made an important discovery; it being no less than Governor Bradford’s manuscript History. He then took from his pocket a duodecimo volume, entitled ‘A History of the Protestant Episcopal Church in America, by Samuel, Lord Bishop of Oxford. Second edition. London 1846,’ – which a few days before had been lent to him by a friend, – and pointed out certain passages in the text, which any one familiar with them would at once recognize as the language of Bradford, as cited by Morton and Prince; but which the author of the volume, in his foot-notes referred to a ‘MS. History of the Plantation at Plymouth, & c., in the Fulham Library.’ There were other passages in the volume, not recognized as having before been printed, which referred to the same source. I fully concurred with Mr. Barry in the opinion that this Fulham manuscript could be no other than Bradford’s History, either the original or a copy, – the whole or a part; and that measures should at once be taken to cause an examination of it to be made.” (History of Plymouth Plantation p. v)

Deane promptly wrote a letter to Reverend Joseph Hunter, one of the Vice-Presidents of the Society of Antiquaries of London, asking him to find out whether the document in the Bishop’s library was indeed Bradford’s original manuscript.

After a thorough examination of the document, Hunter replied to Deane’s letter and declared: “There is not the slightest doubt that the manuscript is Governor Bradford’s own autograph” (History of Plymouth Plantation p. viii).

Despite the revelation, the British government didn’t offer to give the manuscript back and instead created a copy of it, which it sent to Boston in August of 1855.

The transcription of the manuscript arrived on August 3, 1855, and was accompanied by a letter from Hunter, in which he described the original manuscript’s appearance, saying that it was in rough shape after years of mishandling:

“The volume is a folio of twelve inches by seven and a half. The backs of white parchment, soiled, and in no good condition. There has been some scribbling on the cover, now scarcely legible, It was done by some members of Bradford’s family, before they had allowed the volume to pass out of their hands.” (History of Plymouth Plantation p. x).

The original manuscript was written on only one side of each page. On the back of the pages, Bradford sometimes wrote footnotes to help further explain the text. Prince sometimes appeared to write his own notes on these blank pages while he was using the book for his research. All of these notes were transcribed and included in the copy of the manuscript.

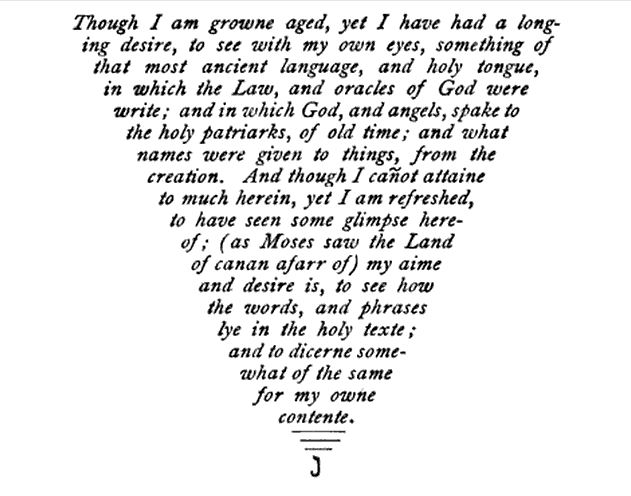

Interestingly, Hunter also stated in his letter that something else was intentionally left out of the transcription of the manuscript: about eight pages of Hebrew quotations from the Old Testament Scriptures, which is located in the front section of the manuscript book, as well as a collection of Hebrew Roots and a note by Bradford about why he included them in his manuscript. According to Hunter’s letter, Bradford’s note read:

“Though I have growne aged, yet I have had a longing desire to see, with my owne eyes, somthing [sic] of that most ancient language, and holy tongue, in which the Law and oracles of God were write; and in which God, and angels, spake to the holy patriaks of old time; and what names were given to things, from the creation. And though I canot attaine to much herein, yet I am refreshed to have seen some glimpse hereof (as Moyses saw the land of Canan a farr of). My aime and desire is, to see how the words and phrases lye in the holy texte; and to discerne somewhat of the same, for my owne contente.” (History of Plymouth Plantation p. xiv).

It’s not clear why the transcriber did not include the Hebrew texts or Bradford’s note in the copy of the manuscript. Perhaps they were left out because they are in a foreign language and, since they are religious scripture and vocabulary lists, are not directly related to the history of the colony.

As a result of its omission, the Hebrew texts were therefore not included when the Massachusetts Historical Society published the manuscript in 1856, although Dean does mention them and quotes Bradford’s note about them in the editorial preface of the book.

Deane ends his editorial preface by pondering how the manuscript ended up in England in the first place and when it arrived:

In conclusion, it would be a satisfaction to know by whose agency the original manuscript of this History was transferred from the New England Library in Boston to the Fulham Library in England. There was no faithful Prince to make a record of this. It is uncertain how long the volume has reposed at Fulham. The Bishop of Oxford, in a note to me on this point, writers: ‘I should suppose for a very long period. I discovered it for myself in searching for original documents for my History of the American Episcopal Church.’” (History of Plymouth Plantation p. xix).

After the manuscript was published in 1856, its description of the First Thanksgiving at Plymouth, sparked a sudden interest in the Thanksgiving holiday, which was up until then only a regional New England tradition and not the national holiday it later became.

Legal Battle Over the Manuscript:

The discovery of the original manuscript ignited a long debate between British and American scholars and politicians about its rightful home.

In 1860, Robert Charles Winthrop, speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, suggested to the Bishop of London at the time, Archibald Campbell Tait, that the Prince of Wales return the manuscript to the United States during his upcoming visit, but the bishop refused.

In 1868, Bishop Tait was appointed Archbishop of Canterbury and was replaced by John Jackson.

In 1869, John Lothrop Motley, minister to England, asked the new bishop to return the manuscript but he also refused, explaining that the manuscript would not be returned without an act of Parliament.

In 1877, scholar Justin Winsor visited Fulham to ask the bishop once again to return the manuscript but found that the bishop was away.

In 1880, William Watson Goodwin, a Harvard professor, visited England and attended a garden party at Fulham Palace, during which he viewed the manuscript, and when he mentioned the book to the bishop’s daughter, Miss Jackson, she joked “Will you promise us not to carry it away?” and explained that a number of Americans had come to see it and were obviously very proud of the famous document.

When Goodwin discussed the manuscript with the bishop himself, the bishop jokingly told the chaplain not to let Goodwin see the label on the inside cover, which states “This book is the property of the New England Library” under which someone had written “It now belongs to the Bishop of London’s Library at Fulham,” after which the bishop explained “We don’t know how it came here; we know only that we got it honestly” (New England Quarterly 248).

Goodwin said he submitted a petition during his trip asking that the manuscript be returned, but to no avail.

In 1881, Benjamin Scott, chamberlain of London, proposed in the British newspapers that the manuscript be returned, but nothing came of it.

In 1885, the Bishop of London, John Jackson died and was replaced by Dr. Frederick Temple.

In 1895, Massachusetts Senator George Frisbie Hoar, a member of the American Antiquarian Society, visited England to deliver an address in Plymouth on the 275th anniversary of the landing of the pilgrims.

During the trip he met the American ambassador to Great Britain, Francis Bayard, and told him about his struggle to get the manuscript returned, after which Bayard promised to do everything in his power to help.

Hoar was later able to schedule a visit with the bishop, during which he viewed the manuscript and requested that it be returned, according to a speech he later made in 1897 that was republished in the New England Magazine:

“After looking at the volume and reading the records on the flyleaf, I said:

‘My lord, I am going to say something which you may think rather audacious. I think this book ought to go back to Massachusetts. Nobody knows how it got over here. Some people think it was carried off by Governor Hutchinson, the Tory governor; other people think it was carried off by British soldiers when Boston was evacuated; but in either case the property would not have changed. Or, if you treat it as booty, in which last case, I suppose, by the law of nations ordinary property does change, no civilized nation in modern times applies that principle to the property of libraries and institutions of learning.’

‘Well’ said the bishop, ‘ I did not know you cared anything about it.’

‘Why,’ said I, ‘if there were in existence in England a history of King Alfred’s reign for thirty years, written by his own hand, it would not be more precious in the eyes of Englishmen than this manuscript is to us.’

‘Well,’ said he, ‘I think myself it ought to go back, and if it had depended on me it would have gone back before this. But the Americans who have been here – many of them have been commercial people – did not seem to care much about it except as a curiosity. I suppose I ought not to give it up on my own authority. It belongs to me in my official capacity, and not as private or personal property. I think I ought to consult the Archbishop of Canterbury. And, indeed,’ he added ‘I think I ought to speak to the Queen about it. We should not do such a thing behind her majesty’s back.’

‘I said: ‘Very well. When I go home I will have a proper application made from some of our literary societies, and ask you to give it consideration’” (New England Magazine 379).

Before leaving England, Hoar informed Ambassador Bayard of his conversation with the bishop and Bayard once again vowed to do what he could to help.

After Hoar returned to Massachusetts, he contacted various historical societies and institutions as well as politicians to ask them to sign a formal letter requesting the return of the manuscript, which they did.

The letter was signed by: George F. Hoar, Stephen Salisbury, Edward Everett Hale, Samuel A. Green of the American Society; Charles Francis Adams, William Lawrence, Charles W. Elliot of the Massachusetts Historical Society; Arthur Lord, William M. Evarts, William T. Davis of the Pilgrim Society of Plymouth, Charles C. Beaman, Joseph H. Coate, J. Pierpont Morgan of the New England Society of New York; and Roger Walcott, the Governor of Massachusetts.

In the meantime, the Bishop of London, Dr. Temple, was appointed Archbishop of Canterbury, a position which made it easier for him to assist in the manuscript’s return, and he was succeeded as Bishop of London by Dr. Creighton, a scholar who had received his degree at Harvard University and was a member of the Massachusetts Historical Society, who was also sympathetic to the cause.

In response to the formal letter sent by Hoar, a Consistory Court met in St. Paul’s Cathedral on March 25, 1897, to discuss the manuscript. In the proceedings, the court dubbed to the manuscript the “Log of the Mayflower” and attributed it to a “Captain William Bradford,” indicating that the British misunderstood what it is was and thought it was a log book of a ship written by the ship’s captain.

Finally, on April 12, 1897 the Consistorial and Episcopal Court of London issued a decree ordering that the manuscript be returned to the United States:

“Whereas a petition has been filed in the Registry of Our Consistorial and Episcopal Court of London by you the said Honorable Thomas Francis Bayard as Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary to Her Most Gracious Majesty Queen Victoria at the Court of Saint Jame’s in London on behalf of the President and Citizens of the United States of America wherein you have alleged that there is in our custody as Lord Bishop of London a certain manuscript book known as and entitled ‘The Log of the Mayflower’ containing an account as narrated by Captain William Bradford who was one of the company of Englishmen who left England in April 1620 in the ship known as ‘The Mayflower’ of the circumstances leading to the prior settlement of that company at Leyden in Holland their return to England and subsequent departure for New England their landing at Cape Cod in December 1620 their settlement at New Plymouth and their later history for several years they being the company whose settlement in America is regarded as the first real colonisation of the New England states…We as Lord Bishop of London had fully recongised the value and interest of the said manuscript book to the citizens of the United States of America and the claims which they have to its possession and that We were desirous of transferring it to the said President and citizens…And after hearing counsel in support of the said application the judge being of the opinion that the said manuscript book had been upon the evidence before the court presumably deposited at Fulham Palace sometime between the year 1729 and the year 1785 during which time the said colony was by custom within the Diocese of London for purposes Ecclesiastical and the registry of the said Consistorial Court was a legitimate registry for the custody of registers of marriages births and deaths within the said colony and that the registry at Fulham Palace was a registry for historical and other documents connected with the colonies and possessions of Great Britain beyond the seas so long as the same remained by custom within the Diocese of London and that on the Declaration of Independence of the United States in 1776 the said colony had ceased to be within the Diocese of London and the Registry of the court had ceased to be a public registry for the said colony and having maturely deliberated on the cases precedents and practice of the Ecclesiastical Court bearing on the application before him and having regard to the special circumstances of the case decreed as follows – (1) That a photographic facsimile reproduction of the said manuscript book verified by affidavit as being a true and correct photographic reproduction of the said manuscript book be deposited in the registry of our said court by or on behalf of the petitioner before the delivery to the petitioner of the said original manuscript book as hereinafter ordered – (2) That the said manuscript book be delivered over to the said Honorable Thomas Francis Bayard by the Lord Bishop of London or in his Lordship’s absence by the registrar of the said court on his giving his undertaking in writing that he will with all due care and dilligence on his arrival from England in the United States convey and deliver in person the said manuscript book to the governor of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States of America at his official office in the State House in the city of Boston…(3) That the said book be deposited by the petitioner with the governor of Massachusetts for the purpose of the same being with all convenient speed finally deposited either in the state archives of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the city of Boston or in the library of the historical society of the said commonwealth in the city of Boston as the governor shall determine — (4) That the governors of the said commonwealth for all time to come be officially responsible for the safe custody of the said manuscript book…(a) That all persons have such access to the said manuscript book… (b) That all persons desirous of searching the said manuscript book for the bona fide purpose of establishing or tracing a pedigree through persons named in the last five pages thereof or in any other part thereof shall be permitted to search the same under such safeguards as the Governor for the time being shall determine on payment of a fee to be fixed by the governor — (c) That any person applying to the official having the immediate custody of the said manuscript book for a certified copy of any entry contained in proof of marriage birth or death of persons named therein or of any other matter of like purport for the purpose of tracing descents shall be furnished with such certificate on the payment of a sum not exceeding one dollar — (d) That with all convenient speed after the delivery of the said manuscript book to the governor of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts the governor shall transmit to the registrar of the court a certificate of the delivery of the same to him by the petitioner…Wherefore We the Bishop of London aforesaid well weighing and considering the premises do by virtue of our authority ordinary and episcopal and as far as in us lies and by law we may or can ratify and confirm such decree of our Vicar General and Official Principal of Our Consistorial and Episcopal Court of London…Harry W. Lee. Registrar” (1898 edition of Bradford’s History pp. xxi-xxviii).

The decree was printed on two pages of manilla paper and inserted into the manuscript book. Another sheet of manilla paper was pasted on the inside cover of the manuscript book with a note that read:

“Consistory Court of the Diocese of London

In the matter of the application of The Honorable Thomas Francis Bayard. Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary in London of the United States of America, for the delivery to him, on behalf of the President and Citizens of the said States, of the original manuscript book entitled and known as the Log of the Mayflower.

Produced in Court this 25th day of March, 1897, and marked with the letter A.

Harry W. Lee

Registrar,

1 Deans Court

Doctors Common” (1898 edition of Bradford’s History pp. iv-v)

On April 29, 1897, the manuscript was officially turned over to Ambassador Francis Bayard for the journey to the United States.

Finally, on May 26, 1897, Ambassador Bayard officially presented the manuscript to Massachusetts Governor Roger Walcott during a ceremony held in Walcott’s office in the Massachusetts State House.

At the ceremony, Senator Hoar made a speech in which he described the long struggle to bring the manuscript back to Massachusetts and thanked Bayard for his help:

“You are entitled, sir, to the gratitude of Massachusetts, to the gratitude of every lover of Massachusetts and of every lover of the country. You have succeeded where so many others have failed, and where so many others would have been likely to fail. You may be sure that our debt to you is fully understood and will never be forgotten.” (1898 edition of Bradford’s History p. lviii)

To celebrate, the American Antiquarian Society held a banquet that evening at the Parker House Hotel in Boston for its 34 members and 10 invited guests, which included Governor Walcott, Ambassador Bayard, the British Consul General and descendants of the Bradford and Winslow families.

Although the repository where the manuscript would be held was not immediately selected, Governor Walcott ultimately decided to deposit the manuscript in the State Library of the Massachusetts State House where it still resides today.

Sources:

Bradford, William. Bradford’s History of Plymouth Plantation, 1606-1646. Vol. 10, Edited by William T. Davis, 1908.

Johns Hopkins University Studies in Historical and Political Science. Vol. I, Edited By Herbert B. Adams, The John Hopkins Press, 1883.

Bradford, William. History of Plymouth Plantation. Edited by Charles Deane, 1856.

“The Pilgrim Myth: The Legends About the Forefathers Persistently Defy History.” Life Magazine, 26 Nov. 1945, pp. 51-57.

Searching for details concerning, was William Bradford a slave owner?