Spectral evidence is a form of evidence based on dreams and visions. It was witness testimony that a person’s spirit or specter appeared to the witness in a dream or vision and afflicted them.

When Was Spectral Evidence Allowed?

In English tradition, spectral evidence was not accepted as evidence in a witchcraft trial, according to an article on the Massachusetts Trial Court Law Libraries blog:

“In the English tradition, although the rules of evidence were vague, legal experts insisted on clear and ‘convincing’ proof of a crime…So-called ‘spectral evidence,’ in which a victim testifies to experiencing an attack by a witch in spirit form, invisible to everyone else, was not accepted as evidence.”

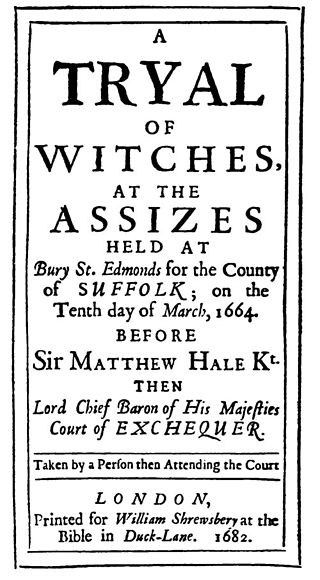

Yet, in 1662, Sir Matthew Hale solidified the legal credibility of spectral evidence in witchcraft cases by allowing it in the Bury St. Edmund case in England, thus setting a precedent to be used at Salem in 1692.

Sir Matthew Hale later wrote a book about the trial, titled the Tryal of Witches, which was published in 1682. The Salem Witch Trials judges referred to the Bury St. Edmund case and Hale’s book and cited it as a reason to allow spectral evidence, according to Cotton Mather, in his book Wonders of the Invisible World:

“Now, one of the latest printed accounts about a Tryal of Witches, is of what was before him, and it ran on this wise. [Printed in the Year 1682.] And it was here the rather mentioned, because it was a Tryal, much considered by the judges of New England” [Mather 111].

Yet another factor that allowed for the use of spectral evidence was the fact that the colony’s charter, and therefore previous laws, which had prohibited spectral evidence, had been revoked and replaced with a new charter in 1691, according to the Massachusetts Trial Court Law Libraries blog:

“The Salem witchcraft trials of 1692 happened at the worst possible time. The charter of the colony had been temporarily suspended (1684-1691) due to political and religious friction between the colony and England. A new charter (1691) arrived from England in May 1692, along with the new governor, but as yet, the General Court had not had time to create any laws. Nevertheless, the new governor created a special court, the Court of Oyer and Terminer [‘to hear and determine’] to deal with the witch cases. The commission that created this court said that the judges were to act ‘according to the law and custom of England and of this their Majesties’ Province.’ But this ignored the difference between the laws of England and the old laws of New England. In the absence of guidance by specific colony laws, and acting in consonance with the general paranoia of the community, the judges famously accepted ‘spectral evidence,’ and other untrustworthy kinds of evidence, as proof of guilt.”

As a result, the courts decided to accept three kinds of evidence: 1) confession, 2) testimony of two eyewitnesses to acts of witchcraft or 3) spectral evidence.

Supplementary evidence was also allowed and included the presence of witches’ marks on the accused person’s body.

Although Reverend Increase Mather didn’t agree with the use of spectral evidence, he argued in his book, Cases of Conscience, that even though it was allowed in the Salem Witch Trials, it was only used as supporting evidence and was never used exclusively to convict someone, although this claim is highly debatable:

“Having therefore so arduous a case before them, pity and prayers rather than censures are their due; on which account I am glad that there is published to the world (by my son) a Breviate of the Tryals of some who were lately executed, whereby I hope the thinking part of mankind will be satisfied, that there was more than that which is called spectre evidence for the conviction or the persons condemned…And the judges affirm, that they have not convicted anyone merely on the account of what spectres have said, or of what has been represented to the eyes or imaginations of the sick bewitched persons” (Mather 285-286).

Critics of Spectral Evidence:

Not everyone agreed with allowing spectral evidence to be used in the trials. There were several vocal critics of spectral evidence who made their opinions known.

On August 9, 1692, Robert Pike, the Massachusetts Bay councilor and Salisbury magistrate, wrote a personal letter to Judge Corwin to express his concerns with the admission of spectral evidence in the trials:

“I further humbly present to consideration the doubtfulness and unsafety of admitting spectre testimony against the life of any who are of blameless conversation, and plead innocent, from the uncertainty of them; for, as for diabolical visions, apparitions, or representations, they are more commonly false and delusive than real, and cannot be known when they are real and when feigned, but by the devil’s report, and then not to be believed, because he is the father of lies. 1. Either the organ of the eye is abused, and the eye and the sense deluded, so as to think they do see or hear some thing or person when indeed they do not, and this is frequent with common jugglers. 2. The devil himself appears in the shape or likeness of a person or thing, when it is not the person or thing itself; so he did in the shape of Samuel. 3. And sometimes persons or things themselves do really appear, but how is it possible for any one to give a true testimony who possibly did see neither shape nor person, but were deluded, and if they did see anything, they know not whether it was the person or but his shape. All that can be rationally or truly said in such as case is this: that I did see the shape or likeness of such a person, if my senses or eyesight were not deluded; and they can honestly say no more, because they know no more, except the devil tells them more; and if he do, they can but say he told them so. But the matter is still incredible: first, because it is but their saying the devil told them so; if he did so tell them, yet the verity of the thing still remains unproved, because the devil was a liar and a murderer (John VIII, 44), and may tell these lies to murder an innocent person” (New England Magazine 33).

On October 8, 1692, Boston merchant Thomas Brattle wrote a letter to an unnamed English clergyman, which circulated widely in the colony, in which he criticized the Salem Witch Trials and its use of spectral evidence, among other things:

“The S.G. will by no means allow, that any are brought in guilty, and condemned, by virtue of spectre evidence (as it is called,) i.e. the evidence of these afflicted persons, who are said to have spectral eye; but whether it is not purely by virtue of these spectre evidences, that these persons are found guilty, (considering what before has been said,) I leave you, and any man of sense, to judge and determine. When any man is indited [sic] for murthering [sic] the person of A.B. and all the direct evidence be, that the said man pistolled the shadow of the said A.B. tho’ there be never so many evidences that the said person murthered C. D. E. F. and ten more persons, yet all this will not amount to a legal proof, that he murthered A.B., and upon the indictement [sic], the person cannot be legally brought in guilty of the said indictement; it must be upon this supposition, that the evidence of a man’s pistolling the shadow of A.B. is a legal evidence to prove that the said man did murther the person of A.B. Now no man will be so much out of his wits as to make this a legal evidence; and yet this seems to be our case; and how to apply it is very easy and obvious” (Narratives of the Witchcraft Cases 176).

In mid-October of 1692, a book titled Some Miscellany Observations on Our Present Debates Regarding Witchcraft in a Dialogue Between S & B by P.E. and J.A. by Samuel Willard was published and criticized the use of spectral evidence in the Salem Witch Trials:

“B. Do the Afflicted persons know personally all whom they cry, out of?

S. `No, some they never saw, it may be never heard of before.

I3. And upon whose information will you fend for the accused?

S. `That of the Afflicted.

II. And who informed them?

S. `The Spectre.

B. Very good, and that’s the Devil, turned informer: how are good men like to fare, against whom he hath a particular malice.” (Willard 280).

In October of 1692, Reverend Cotton Mather published his book Wonders of the Invisible World which said spectral evidence should be allowed but also said that it isn’t enough to convict someone:

“When there has been a murder committed, an apparition of the slain party, accusing of any man, although such apparitions have oftner spoke true than false, is not enough to convict the man as guilty of that murder; but yet it is a sufficient occasion for magistrates to make a particular enquiry, whether such a man have afforded any ground for such an accusation. Even so a spectre exactly resembling such or such a person, when the neighbourhood are tormented by such spectres, may reasonably make magistrates inquisitive whether the person so represented have done or said any thing that may argue their confederacy with evil spirits…” (Mather 28).

In November or December of 1692, Reverend Increase Mather published his book Cause of Conscience Concerning Evil Spirits in which he argued that it is an unreliable form of evidence.

In the book, Mather argued that spectral evidence isn’t valid because specters can take the shape of innocent people. Mather referenced scriptures from the Bible and historical stories to illustrate his point:

“Argu I. There are several scriptures from which we may infer the possibility of what is affirmed. I. We find that the devil by the instigation of the witch at Endor appeared in the likeness of the prophet Samuel…But that is was a demon represent Samuel has been evidenced by learned and orthodox writers: especially (e) Peter Martyr, (f) Balduinus, (t) Lavater, and our incomparable John Rainolde…And that evil angels have sometimes appeared in the likeness of of living absent persons is a thing abundantly confirmed in history…Paulus and Palladius did both of them profess to Austin, that one in his shape had divers times, and in divers places appeared them (k) Thyreus; mentions several apparitions of absent living persons, which happened in his time…Nevertheless, it is evident from another scripture, viz, that in, 2 Cor 11. 14. For Satan himself is transformed into an Angel of light. He seems to be what he is not, and makes others seem to be what they are not…A third scripture to our purpose is that, in Re: 12 10 where the devil is called the accuser of the brethren…” (Mather 228-231).

Mather also stated that another cause of these visions and specters is that the afflicted persons might be possessed by evil spirits.

As a religious man, Mather’s main problem with the use of this spectral evidence though isn’t the legal consequences of it but the religious ones:

“This then I declare and testify, that to take away the life of any one, merely because a spectre or devil, in a bewitched or possessed person does accuse them, will bring the guilt of the innocent blood on the land, where such a thing shall be done: Mercy forbid that it should, (and I trust that as it has not it never will be so) in New-England” (Mather 255).

When Was Spectral Evidence Outlawed?

In October of 1692, Governor Phips dissolved the court of Oyer and Terminer due to his dissatisfaction with some types of evidence used in the court, particularly spectral evidence and the touch test, according to a letter Phips wrote to the Earl of Nottingham in February:

“The Court still proceeding in the same method of trying them, which was by the evidence of the afflicted persons who when they were brought into the Court as soon as the suspected witches looked upon them instantly fell to the ground in strange agonies and grevious torments, but when touched by them upon the arm or some other part of their flesh were immediately revived and came to themselves, upon [which] they made oath that the Prisioner at the Bar did afflict them and that they saw their shape or spectre come from their bodies which put them into such pains and torments: When I enquired into the matter I was informed by the Judges that they begun with this, but had humane testimony against such as were condemned and undoubted proof of their being witches, but at length I found that the Devil did take upon him the shape of Innocent persons and some were accused of whose innocency I was well assured and many considerable persons of unblamable life and conversation were cried out upon as witches and wizards. The Deputy Govr. notwithstanding persisted vigerously in the same method, to the great disatisfaction and disturbance of the people, until I put an end to the court and stopped the proceedings, which I did because I saw many innocent persons might otherwise perish and at that time I thought it my duty to give an account thereof that their Ma’ties pleasure might be signifyed, hoping that for the better ordering thereof the Judges learned in the law in England might give such rules and directions as have been practized in England for proceedings in so difficult and so nice a point;”

In January of 1693, a new Superior Court, presided over by Deputy Governor William Stoughton, met in Salem. with instructions from Governor Phips not to accept spectral evidence as proof of guilt, according to Phips’ letter to the earl:

“When I put an end to the Court there ware at least fifty persons in prison in great misery by reason of the extream cold and their poverty, most of them having only spectre evidence against them and their mittimusses being defective, I caused some of them to be let out upon bail and put the Judges upon consideration of a way to relief others and to prevent them from perishing in prison, upon which some of them were convinced and acknowledged that their former proceedings were too violent and not grounded upon a right foundation bu that if they might sit again, they would proceed after another method, and whereas Mr. Increase Mathew and several other Divines did give it as their Judgement that the Devil might afflict in the shape of an innocent person and that the look and touch of the suspected persons was not sufficient proof against them, these things had not the same stress laid upon them as before, and upon this consideration I permitted a special Superior Court to be held at Salem in the County of Essex on the third day of January, the Lieut Govr. being Chief Judge.”

Nonetheless, after the remaining 52 people had been tried, three were found guilty and were sentenced to death but were reprieved after King William’s attorney general wrote to Phips and expressed concern that these three were convicted under similar circumstances as the others, which indicates that they had possibly been convicted using spectral evidence or some other type of unreliable evidence, according to Phips’ letter to the earl:

“and I was informed by the Kings Attorney General that that some of the cleared and the condemned were under the same circumstances or that there was the same reason to clear the three condemned as the rest according to his Judgement.”

The reprieve enraged Stoughton, who refused to sit on the bench of the court in protest and Phips pointed out that Stoughton had been eager to convict the accused from the very beginning, according to Phips’ letter:

“The Lieut. Gov. upon this occasion was enraged and filled with passionate anger and refused to sit upon the bench in a Superior Court then held at Charles Towne, and indeed hath from the beginning hurried on these matters with great precipitancy and by his warrant hath caused the estates, goods and chattles of the executed to be seized and disposed of without my knowledge or consent.”

It is highly possible though that Phips, as the governor of the colony, was just trying to pass the blame for the Salem Witch Trials onto someone else and, since Stoughton was the chief justice in the trials, he was an easy target.

The Salem Witch Trials was the first and last time spectral evidence was allowed in a trial.

Sources:

Mather, Cotton. The Wonders of the Invisible World. London: John Russell Smith, 1862.

Narratives of the Witchcraft Cases 1648-1706. Edited by George Lincoln Burr, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1914.

Willard, Samuel. “Some Miscellany OBSERVATIONS On Our Present Debates Respecting Witchcrafts.” Jahrbuch Für Amerikastudien, vol. 9, 1964, pp. 271–284. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41155285.

Withington, Nathan N. “Robert Pike, A Forgotten Champion of Freedom.” New England Magazine, Warren F. Kellogg, Sept. 1897-Feb. 1898.

“Two Letters of Gov. William Phips (1692-1692).” Famous American Trials, University of Missouri-Kansas City, law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/salem/ASA_LETT.HTM

“Some Miscellany.” Salem Witch Trials Documentary Archive and Transcription Project, salem.lib.virginia.edu/texts/willard/index.html

Louis-Jacques, Lyonette. “Salem Witch Trials: A Legal Bibliography.” University of Chicago Library News, 29 Oct. 2012, news.lib.uchicago.edu/blog/2012/10/29/the-salem-witch-trials-a-legal-bibliography-for-halloween/

“Witchcraft Law Up to the Salem Witchcraft Trials of 1692.” Massachusetts Law Updates, blog.mass.gov/masslawlib/civil-procedure/witchcraft-law-up-to-the-salem-witchraft-trials-of-1692/

“Ask the Archivist.” Salem Witch Trials Documentary Archive and Transcription Project, salem.lib.virginia.edu/archivist.html

Pin it for later: