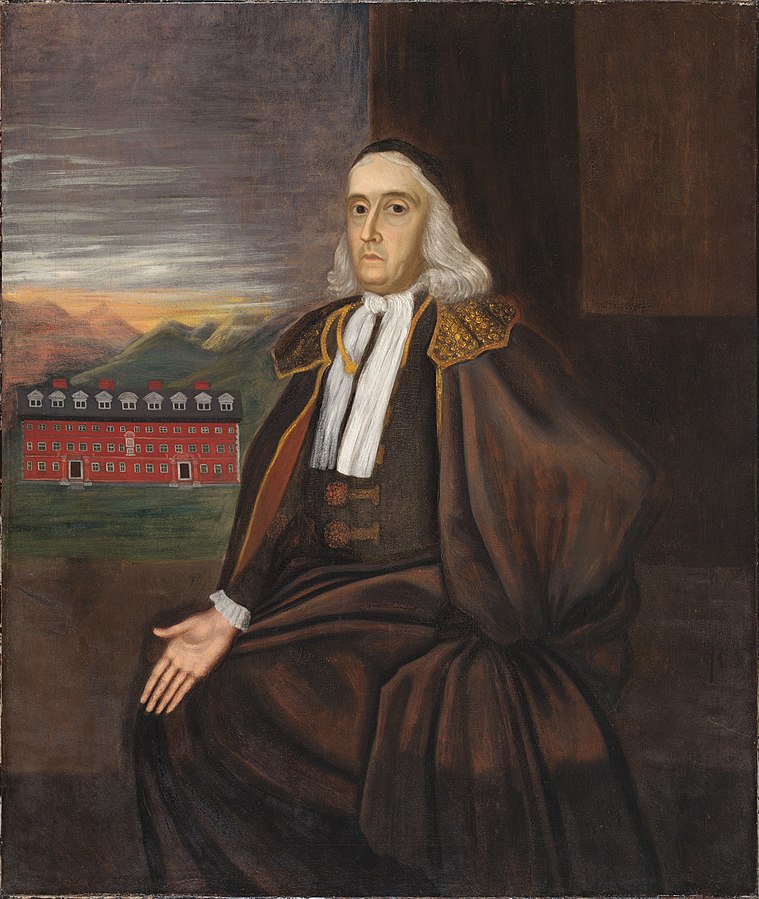

William Stoughton was a colonial magistrate for the Massachusetts Bay Colony and the Chief Magistrate of Court of Oyer and Terminer during the Salem Witch Trials.

Early Life:

William Stoughton was born in 1631 to Israel and Elizabeth (Knight) Stoughton. It is not known if Stoughton was born in England or the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

Stoughton was educated at Harvard University where he earned a degree in theology in 1650. He continued his education at the University of Oxford and earned his Masters in Arts in 1653.

In 1660, Stoughton served as a curate in Sussex, England but he lost that position in 1662 in the crackdown on religious dissenters that took place after King Charles II was restored to the throne.

Since he had very little prospects left in England, Stoughton returned to the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1662 and served as a clergyman in Dorchester, Massachusetts.

From 1671 to 1674, Stoughton served as a selectman in Dorchester and from 1674 to 1676, he served as commissioner for the New England Confederation.

In 1676, Stoughton was sent to England with Peter Bulkeley to prevent attempts by Robert Mason, who was the proprietor of the neighboring Province of Maine, to have the Massachusetts Bay Colony charter revoked.

From 1684 to 1686, Stoughton served as the temporary Deputy President of the Dominion of New England and was then appointed Deputy to Governor Joseph Dudley in 1686.

On March 3, 1687, Stoughton was appointed Judge Assistant to Governor Joseph Dudley.

On March 14, 1692, Stoughton was appointed Lieutenant Governor of Massachusetts.

William Stoughton in the Salem Witch Trials:

On May 27, 1692, Governor William Phipps established a special court to hear the Salem Witch Trials cases, the Court of Oyer and Terminer, and appointed Stoughton as the Chief Magistrate of the court.

As chief justice, Stoughton presided over the trials and issued death warrants for the convicted witches.

Despite the fact that spectral evidence, claims of visions and the spirit of the accused attacking the victim, was no longer allowed in British courts, Stoughton allowed for the use of spectral evidence in most cases during the Salem Witch Trials.

This went against the advice of the committee of Boston ministers who warned the court that spectral evidence was unreliable because the Devil could assume the shape of anyone and cause these spectres to attack their victims.

Stoughton was a very orthodox Puritan who supported the Calvinistic concept of consent and covenant and so therefore believed that the Devil could only assume the shape of someone who had covenanted with him. It seems that he convinced the other judges on the court to believe the same (Cowing 94.)

Although Stoughton’s ideas seemed extreme, he believed he was doing what was best for the colonial officials given the circumstances, according to Cedric B. Cowing in his book The Saving Remnant:

“Under these circumstances, the decisions of Stoughton, Hathorne and the majority make sense. To admit that the Devil could take any person’s shape without consent would be to admit their impotence against witches and weaken their political authority at a time when they were trying to reassert it. To let witches off on the ground that there was too little evidence other than the spectral would also make them appear ineffectual in a crisis. They chose the middle position: for which there was precedent: the Devil could impersonate only those who signed a pact and sold their souls to him. This interpretation led to heavy reliance on spectral evidence and consequent prosecutions and convictions” (Cowing 95.)

Stoughton also made another controversial decision in the trials when Rebecca Nurse was found not guilty during her trial on June 29, 1692 and the “afflicted girls” raised such an outcry in the courtroom that Stoughton asked the jury to reconsider their verdict (Goss 24.)

Stoughton told the jury that perhaps they had not heard a reportedly incriminating statement that Nurse made during her trial when she described fellow accused witch Goody Hobs as “one of us.”

When the foreman of the jury, Thomas Fiske, asked Rebecca Nurse about the meaning of her statement, she didn’t answer, probably due to her partial deafness.

As a result, the jury deliberated and came back with a guilty verdict and Stoughton sentenced Nurse to be executed on July 19, 1692.

After hearing hundreds of cases and executing 19 people, the Court of Oyer and Terminer was officially dissolved by Governor Phips in October of 1692.

On December 22, Stoughton was appointed Chief Justice of the Massachusetts Superior Court to hear the remaining witchcraft cases with instructions from Governor Phips not to accept spectral evidence as proof of guilt.

After the Superior Court officially met in December and 40 of the remaining witchcraft cases were heard, three of the accused were found guilty and were sentenced to death.

Shortly after, the three were reprieved when King William’s attorney general wrote to Governor Phips and expressed concern about the evidence used to convict them, indicating that spectral evidence may have been used.

The Superior Court learned of the reprieve when the court met again on February 1.. Stoughton was enraged and refused to sit on the bench in protest, according to a letter from Governor Phips to the Earl of Nottingham in February of 1693:

“The Lieut. Gov. upon this occasion was enraged and filled with passionate anger and refused to sit upon the bench in a Superior Court then held at Charles Towne, and indeed hath from the beginning hurried on these matters with great precipitancy and by his warrant hath caused the estates, goods and chattles of the executed to be seized and disposed of without my knowledge or consent” (“SWP No. 163: Two Letters of Gov. William Phips”.)

According to Increase Mather in his book, A Further Account of the Tryals of the New England Witches, Stoughton declared that by reprieving these three people “the Kingdom of Satan was advanced, etc, and the Lord have mercy on this country.”

Stoughton refused to sit on the bench for the next three days and another judge, Judge Danforth, had to fill in for him, during which five or six people were pardoned and five or six more were tried and acquitted.

Stoughton returned to oversee the remaining cases in late April and early May and those remaining cases ended in acquitted as well.

William Stoughton After the Salem Witch Trials:

From 1694 to 1699. Lieutenant Governor Stoughton served as the acting governor of Massachusetts after Governor Phips was recalled to England and mysteriously died shortly after his arrival in England.

In the three years after the trials, the colony was struck by a series of hardships such as crops failures, droughts, smallpox outbreaks and Native American attacks and the colonists began to to fear that God was angry at them for putting innocent people to death during the Salem Witch Trials.

As acting governor, on December 17, 1696, Stoughton issued a proclamation calling for a day of prayer and fasting to appease God for any wrongdoings during the Salem Witch Trials.

On the day of prayer of fasting, January 14, 1697, Judge Samuel Sewall issued a public apology for his role in the Salem Witch Trials.

According to Governor Thomas Hutchinson in his 1870 book The Witchcraft Delusion of 1692, after Sewall issued the apology Stoughton refused to issue his own apology:

“It is said that the chief justice Mr. Stoughton being informed of this act of one of his brethren, remarked upon it, that for himself, when he sat in judgment he had the fear of God before his eyes, and gave his opinion according to the best of his understanding, and although it might appear afterwards that he had been in an error, he saw no necessity of a public acknowledgment of it” (Hutchinson 41.)

Stoughton again served as acting governor of the colony in 1700 to 1701.

Stoughton also continued to serve as chief justice of the Massachusetts courts until he died at his home in Dorchester on July 7, 1701.

At Stoughton’s funeral, Reverend Samuel Willard delivered his funeral sermon during which he described Stoughton as “the last of the original Puritans.”

Stoughton was buried in a tomb at the Dorchester North Burying Ground in Dorchester.

Since Stoughton never married and didn’t have children, he left a portion of his estate and his mansion to his nephew William Tailer.

When the neighboring town of Stoughton, Massachusetts was settled in 1713 and officially incorporated in 1726, it was named after William Stoughton.

Sources:

Mather, Increase. A Further Account of the Tryals of the New-England Witches. J Dunton, 1693.

Hutchinson, Thomas. The Witchcraft Delusion of 1692. Privately Printed, 1870.

Baker, Emerson W. A Storm of Witchcraft: The Salem Witch Trials Experience. Oxford University Press, 2014.

Cowing, Cedric B. The Saving Remnant: Religion and the Settling of New England. University of Illinois Press, 1995.

Goss, K. David. The Salem Witch Trials: A Reference Guide. Greenwood Press, 2008.

Burrill, Ellen Mudge. The State House, Boston, Massachusetts. Wright and Potter Printing Company, 1924.

“SWP No. 163: Two Letters of Gov. William Phips (1692-1693).” Salem Witch Trials Documentary Archive and Transcription Project, salem.lib.virginia.edu/n163.html

Dom, Nathan. “Evidence from the Invisible Worlds in Salem.” Library of Congress, 20 Aug. 2020, blogs.loc.gov/law/2020/08/evidence-from-invisible-worlds-in-salem/

“Dorchester North Burying Ground.” City of Boston, boston.gov/cemeteries/dorchester-north-burying-ground

“Grave of Lieutenant William Stoughton.” Digital Commonwealth, digitalcommonwealth.org/search/commonwealth:fj237316w

“William Stoughton.” Stoughton History, Stoughton Historical Society, www.stoughtonhistory.com/williamstoughton.htm