The War of 1812 was a war between the United States and Britain which greatly affected Massachusetts.

The war was the result of British interference in American trade and the impressment of American sailors into the British navy.

The New England states, particularly Massachusetts, strongly opposed the War of 1812 because they felt it was unnecessary and worried it would negatively impact New England’s economy.

The United States officially declared war on Great Britain on June 18, 1812, after the House of Representatives and the Senate narrowly voted in favor of it.

In response, on June 26, 1812, the Massachusetts House of Representatives condemned the war and voted against it 406 to 240. The Massachusetts House called the decision for war “an event awful, unexpected, hostile to your interests, menacing to your liberties, and revolting to your feelings.”

Yet, the minority members of the house, who had voted in favor of the war, issued a report stating that they did not believe “the people of Massachusetts are unmindful of the example of their ancestors, who in the most perilous times ‘took’ no ‘counsel from fear'” and urged people to support the national government “with that energy and firmness which becomes a free people.”

Despite the House voting against the war, the Massachusetts Senate passed a resolution approving the war and declared it both just and necessary.

On July 15, 1812, a meeting was held in Faneuil Hall during which the war was denounced and President James Madison was vilified. Prominent speakers at the meeting were Daniel Sargeant, Harrison Gray Otis and Josiah Quincy.

On August 5, 1812, the Massachusetts Governor Caleb Strong refused to commit the Massachusetts state militia to the war effort.

In response to Massachusetts’ refusal to send troops to the war, President Madison refused to send troops to Massachusetts to protect them from a British invasion.

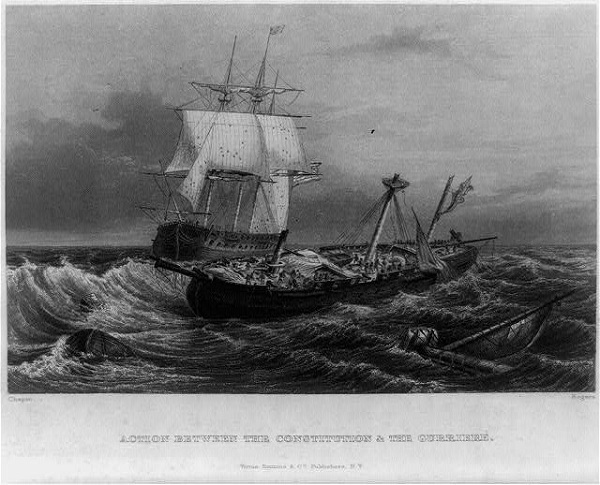

On August 19, 1812, the first major naval battle of the War of 1812 took place when the Boston-based ship, the USS Constitution, fought and defeated the British ship HMS Guerrierre off the coast of Nova Scotia.

The Constitution earned its famous nickname, “Old Ironsides,” that day when several cannonballs fired at the ship simply bounced of its side. The crew declared the sides must be made of iron and several press publications then dubbed the ship “Old Ironsides.”

As the war continued, anti-war sentiment in New England began to grow and New England even began to consider seceding from the United States, according to an article in the Boston Globe:

“Throughout the fall [of 1812], gloom settled around New England. In Boston, many leading citizens became furious at a stupid war going badly and began to threaten action. The Boston Gazette wrote, ‘If James Madison is not out of office, a new form of government will be in operation in the eastern section of the Union.’ Madison was hanged in effigy in Augusta, Maine. Huge rallies filled Faneuil Hall. The Massachusetts House voted 406 to 240 to denounce the war as ‘awful’ and ‘revolting.’ The governor of Massachusetts, Caleb Strong, sent out secret feelers to his counterpart in Halifax. A new kind of flag was occasionally seen around New England, with five stars and five stripes—the five states of New England (Maine was then a district of Massachusetts). Throughout the interior, town meetings expressed deep feelings against the war—in much the same way that earlier generations had protested British tyranny. From these currents came a call for the New England states to convene a meeting at Hartford to consider options. The Hartford Convention began in December 1814, and to its credit, stopped short of any activity that might have led to New England breaking away from the United States. But it was a close call.”

War of 1812 Events in Massachusetts:

At first, the war didn’t affect Massachusetts much because the British spared New England in hopes that they would not engage in hostilities and might even side with Britain and Canada in the conflict.

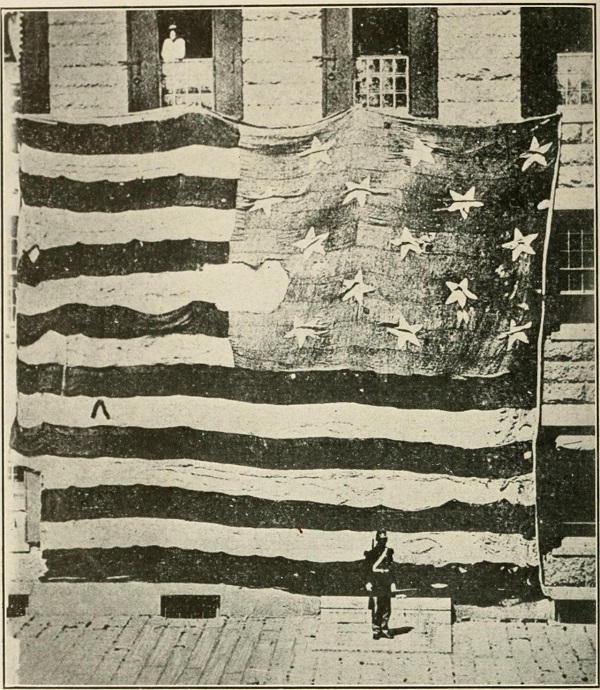

The original “Star Spangled Banner” flown at Fort McHenry during the War of 1812, photographed in the Boston Naval Yard, Boston, Mass, circa 1873.

Britain’s leniency on New England didn’t last though and from the spring of 1813 until the end of the war in 1815, British ships constantly hovered around the Massachusetts coast and threatened to destroy the coastal towns in the state.

Much of the Massachusetts coast was in a British blockade during the war and many coastal towns came under attack from the British navy, particularly in the year 1814 when the British government ramped up its effort to win the ongoing war.

In Cape Cod, the British navy began extorting numerous towns by threatening to attack them if they didn’t pay them, according to the book Attack of the HMS Nimrod: Wareham and the War of 1812:

“British fleet commanders often demanded payment from the various Cape Cod towns in exchange for holding off on an attack. In one case, Admiral Lord Howe sailed the HMS Newcastle to Orleans and proclaimed that if the town did not pay $1,000, he would destroy the salt works. Other Cape towns, including Eastham and Brewster, paid substantial sums to the British to save their salt works. Salt making at the time was an important Cape Cod industry due to the close connection of salt with fishing. Cape Cod was the saltshaker of America. It was the major export and moneymaker of Cape Cod.”

The towns of Barnstable, Falmouth, Sandwich and Orleans were the only towns in Cape Cod who refused to pay the extortion fee which left them vulnerable to attacks by the British.

On June 1, 1813, the Battle of Boston Harbor (otherwise known as the Capture of the USS Chesapeake) took place. This was a battle between the British navy frigate HMS Shannon and the American frigate USS Chesapeake. A total of 80 men were killed and 252 were wounded. The British captured the Chesapeake and took it to Halifax, Nova Scotia were its sailors were imprisoned.

In January of 1814, the British brig Nimrod anchored off the wharf in Barnstable and demanded the artillery pieces and other property there and threatened to fire upon the town if they refused.

On January 28, 1814, the Nimrod sailed to Falmouth and demanded the town’s artillery pieces and threatened to attack the town if it refused. The local militia refused. The Nimrod responded by firing upon the town for several hours before finally leaving. Many buildings were damaged in the bombardment but no lives were lost.

On April 3, 1814, the USS Constitution fled to Marblehead harbor when it was being chased by the HM frigates Tenedos and Junon. The two ships had come across the Constitution when it was attempting to return to Boston after capturing British ships in the West Indies.

The Constitution fled to Marblehead harbor to seek protection from Fort Sewall. While the USS Constitution anchored in the harbor, the Tenedos and Junon anchored six miles off shore to wait the ship out.

The Constitution’s captain worried that Fort Sewall’s defense might not be strong enough to fight off the two ships if they made an attack at nightfall, so the captain snuck out of the harbor and sailed to Salem harbor that afternoon to seek protection from Fort Pickering.

The Constitution stayed there for about a week to wait out the pursuing ships. After the Tenedos and Junon eventually gave up and left, the USS Constitution made its way safely back to Boston and continued to participate in the war. In total, the USS Constitution defeated five British warships during the War of 1812.

“Action between the Constitution and the Guerriere,” engraving by John Rogers and John Reuben, circa 1859

On June 11, 1814, barges from two British ships entered Scituate Harbor and burned several ships before stealing several others.

On June 13, 1814, the British ship the Nimrod bombarded Wareham and burned the cotton factory there after firing upon it with a Congreve rocket. The Nimrod dispatched barges carrying 225 soldiers who invaded the town.

The British captured Captain Bumpus and brought him to his home where they confiscated and destroyed the military supplies stored there. A total of four American schooners, five sloops, a ship, a brig, and a brig-under-assembly at a local shipyard were burned by the British.

After the attack, the Nimrod ran aground in nearby Buzzard’s Bay and, to lighten the ship’s load and prevent it from sinking, the crew threw the ship’s five cannons overboard before sailing on their way. (About 175 years later, in 1987, a diving crew from the Kendall Whaling Museum of Sharon, Mass, found the cannons in the bay and donated one of them to the Falmouth Historical Society where it is still on display today.)

On June 17, 1814, some British frigates and several small ships anchored near Cohasset and demanded a contribution of provisions from the local militia, who refused. Barges from the British ships burned a sloop at or near Cohasset Harbor but it is not clear of this happened on June 17 or on another day in June.

In July of 1814, the British conquered and took over control of Fort Sullivan, in Maine, (Maine was a part of Massachusetts at the time.)

Forts all along the New England coast began strengthening their defenses. This included forts in Bath and Portland, Maine and in Portsmouth, NH, as well as Fort Lilly in Gloucester, Ma, Fort Pickering in Salem, Ma, Fort Sewall in Marblehead, Ma, and Fort Warren and Fort Independence in Boston Harbor.

In September of 1814, Boston expected to be attacked next. Governor Strong finally issued orders on September 6, 1814, for 4,000 troops to march to Boston at once and ordered the state militia to be ready to march to Boston at a moment’s notice.

The troops began to gather on September 8 and were placed under the supervision of Major General Joseph Whiton. By the middle of September in 1814, the city had over 5,000 troops stationed at its various forts and batteries.

The city decided not only to fortify its existing defenses but to also build a new fort in case of attack and called for volunteers to help build it, according to the Records of the Massachusetts Volunteer Militia:

“An attack upon the important City of Boston was confidently expected; it was the capital

of New England, and the moral effect of its capture would be great. It was a place for the construction of American war vessels, which the enemy feared more than armies. On this account also its capture or destruction was desirable. It was also a wealthy town, and offered a rich harvest for plunderers. It was well known too that it was almost defenseless. Caleb Strong, then Governor, was, it was well known, intensely opposed to the war; and it was not until after all her territory east of the Penobscot river in the District of Maine, (then a part of Massachusetts,) was in possession of the enemy, that any energetic measures were taken for its defense. Then a public meeting was called to consider the matter, and a committee consisting of Harrison Gray Otis, and others, was appointed to wait on the Governor, and present to him an address on the defenseless state of the city. The Governor listened to this appeal, and at once instituted measures for the defense of the whole line of the coast of the State, and of the District of Maine. A heavy fort was at once commenced on Noddle’s Island, (now East Boston,) under the supervision of Major Loammi Baldwin as chief engineer; a call was made for volunteers to work on the fortification, and the response was patriotic; large numbers of the citizens of all classes and trades might be seen day after day toiling like common laborers.”

On September 8, 1814, 77-year-old Paul Revere signed a petition volunteering his labor to help Governor Caleb Strong in strengthening Boston’s defense against the threat of attack by the British.

According to the Research Director of the Paul Revere House, Patrick M. Leehey, as a Federalist, Revere opposed the War of 1812 but still felt he had a duty to protect the city from attack.

Revere’s help was accepted and he helped build Fort Strong on Noddle’s Island in September and October of 1814. (Revere’s copper mill, which was run by his son at the time, also created three tons of copper for naval use each week and the American navy used Revere-made cannons during the War of 1812.)

The fort on Noddle’s Island was finished on October 20, 1814 and named Fort Strong in honor of the governor (the fort was later moved to another island in Boston harbor, Long Island, later in the century.) In addition, fortifications were also erected at South Boston Point and on Savin Hill.

Other preventative measures were also taken, such as the purchase of ships that were intended to be sunk in the channel to prevent the British from landing in Boston.

Also, the bridges leading to Boston from the towns of Chelsea, Charlestown, Brighton and Cambridge, were placed under armed guard, with about 50-60 axe-men at each of them who were ordered to destroy the bridges if the British approached.

On September 9, 1814, just after midnight, the Old Stone Fort at Bearskin Neck in Rockport was captured in a sneak attack by the British frigate the Nymphe. Upon capture, the fort was dismantled, the ammunition was looted and all nine seafencibles were taken prisoner.

After one of two barges sent ashore by the British fired a shot upon the town, the force of the shot damaged the barge and sank it. The nine crew members on board were seized and taken prisoner by the townspeople.

The local militia refused to exchange the British prisoners for the American prisoners so the townspeople reportedly negotiated a secret exchange with the British commander themselves.

On December 19, 1814, after a British ship, HMS Newcastle, tried to extort the town of Orleans, in Cape Cod, in an attempt to hold off on an attack, the residents of the town refused. The HMS Newcastle then tried to bombard the town, but the large ship was too big to get within firing range of Orleans. Its cannonballs fell short of the town and did little damage, if any at all.

The local militia gathered and fought off an attempted British landing and invasion. Several British sailors were killed before the British finally retreated.

The War of 1812 technically ended on December 24, 1814 when Britain and the United States signed a peace treaty, called the Treaty of Ghent.

It took over a month for news of the treaty to reach all of the British forces though. Unaware of the treaty, British forces in the Gulf Coast launched a major attack on New Orleans in February of 1815, which the Americans won.

On February 12, 1815, the news finally reached Boston that Britain and the United States that the war was over.

On February 17, 1815, the Treaty of Ghent was ratified by the U.S. Senate and Madison declared the war officially over.

Neither Britain or America won the War of 1812 since it ended in a stalemate.

Massachusetts After the War of 1812:

The war changed New England’s economy forever. Since the British navy had New England in a blockade, New Englanders were forced to turn inland to make money.

Cut off from the sea, they began to develop the first river-powered mills which spurred the industrial revolution in Massachusetts and in the country in general, and redefined New England life throughout the 19th century. Manufacturing soon became the staple of the state’s economy and it continued well into the 20th century.

If you want to learn more about the War of 1812, check out the following article about the best books about the War of 1812.

Sources:

Carstens, Patrick Richard and Timothy L. Sanford. Searching For the Forgotten War – 1812: United States of America. Xlibris Corporation, 2011.

Conway, J. North and Jesse Dubuc. Attack of the HMS Nimrod: Wareham and the War of 1812. The History Press, 2014.

Ellis. James H. A Ruinous and Unhappy War: New England and the War of 1812. Algora Publishing 2009.

Triber, Jayne E. A True Republican: The Life of Paul Revere. University of Massachusetts Press, 1998.

The People’s Democratic Guide. James Webster, Vol 1, 1842.

Hickey, Donald R. The War of 1812: A Forgotten Conflict, Bicentennial Edition. University of Illinois Press, 2012.

Austen, George Lowell. The History of Massachusetts, from the Landing of the Pilgrims to the Present Time. B.B Russell, 1876.

Records of the Massachusetts volunteer militia called out by the Governor of Massachusetts to suppress a threatened invasion during the war of 1812-14. Wright & Potter printing Company, 1913.

“A Marblehead Escape.” USS Constitution Museum, 2 April. 20014, ussconstitutionmuseum.org/2014/04/02/a-marblehead-escape/

“Paul Revere and the War of 1812.” Boston Tea Party Museum,www.bostonteapartyship.com/boston-attractions/paul-revere-house/the-war-of-1812-and-paul-revere

“The Battle of Orleans, Massachusetts.” CapeCodHistory.us, capecodhistory.us/20th/Battle_of_Orleans-1814.htm

Widmer, Ted. “The War of 1812? Don’t Remind Me.” Boston Globe, 20 April. 2014, www.bostonglobe.com/ideas/2014/04/19/the-war-don-remind/rrwS3yG3xCAMqih8HUTN9K/story.html

“Why New England Almost Seceded Over the War of 1812.” Radio Boston, 15 June. 2012., radioboston.legacy.wbur.org/2012/06/15/new-england-succession

Hickey, Donald. “An American Perspective on the War of 1812.” PBS.org, Public Broadcast Service, www.pbs.org/wned/war-of-1812/essays/american-perspective/

Horwitz, Tony and Brian Wolly. “10 Things You Didn’t Know About the War of 1812.” Smithsonian Magazine, 21 May. 2012, www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-10-things-you-didnt-know-about-the-war-of-1812-102320130/?no-ist

“War of 1812 Battles, Skirmishes, Raids, Massacres, Occupations, and Invasions.” War of 1812 Magazine, Issue 20, May 2013, www.napoleon-series.org/military/Warof1812/2013/Issue20/Eshlemen2.pdf

“News of Peace Treaty Reaches Boston February 12, 1815.” Mass Moments, www.massmoments.org/moment.cfm?mid=50

“Massachusetts Volunteer Militia in the War of 1812.” Massachusetts American Local History Network, www.ma-roots.org/military/militia/

“The War of 1812: Items from the Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society.” Massachusetts Historical Society, www.masshist.org/features/war-of-1812-selections

Bearskin Neck is in Rockport Ma.

Thank you, I wasn’t sure exactly what town it was in.