Samuel Adams was a patriot who lived in Boston, Massachusetts during the American Revolution.

Adams was also a tax collector and bankrupt businessman who had been accused of embezzling public funds shortly before the revolution began.

Adams, a wealthy nobleman and cousin of John Adams, had a flair for politics that won him the position of tax collector for the city of Boston in 1756.

Although he was a bad business man who had squandered the earnings from his father’s business just a few years before, Adams was appointed to the job on account of his honesty and willingness to serve the city of Boston.

Adams’ kindhearted nature made him a poor choice for the position. His easy-going disposition made him reluctant to hassle his delinquent taxpayers if they convinced him they couldn’t afford to pay him.

He listened sympathetically to stories of hardship and willingly put off collection of debts for extended periods of time. As a result, his accounts were often enormously short.

Adams avoided detection by merging previous year’s collections with the current year’s to balance his books but this tactic only worked for so long.

In 1764, his deficits were finally discovered, which by then amounted to seven thousand pounds. Despite his inefficiency as a tax collector, he was so well liked by the taxpayers and had such a reputation for honesty that they never accused him of stealing and reelected him for another year.

Due to the town meeting being on the verge of bankruptcy, Adams was forced to file lawsuits against the delinquent taxpayers but the taxes were never collected.

Historian John C. Miller’s book titled Sam Adams: Pioneer in Propaganda, suggests that Adams stole the money and was saved solely by the political chaos of the Stamp Act controversy:

“His shortages grew alarming and to make matters worse, he began to take money for his own use from the funds he had collected for the town of Boston and Suffolk county…Just when Adams’s prospects seemed blackest, news of the Stamp Act reached Boston and public attention was diverted away from his financial irregularities. Had not the British government attempted to raise a colonial revenue at this critical juncture of Sam Adams’s career he might have stood trial for embezzlement.”

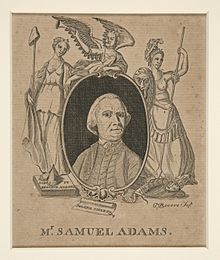

Engraving of Samuel Adams by Paul Revere published in Royal American Magazine in 1774

A few years later, in 1767, he did. After Sam Adams resigned as Tax Collector, he was working as a clerk for the House of Representatives when he was sued by the town treasurer for four thousands pounds worth of uncollected taxes.

It is speculated that the lawsuit was a plan hatched by his Tory enemies, like Massachusetts Governor Thomas Hutchinson, to tarnish his reputation and keep him too busy to participate in his patriotic activities, such as leading the Sons of Liberty in protests against the British government.

Fortunately, Adams won his case with the help of his old friend James Otis, who was the attorney representing the town treasurer.

But Otis had no power over the appellate bench who overturned the ruling and ordered Adams to pay a reduced sum of fourteen hundred pounds.

Adams was given several extensions to raise the money over a number of years. These extensions were contested by Foster Hutchinson, brother of Thomas, who drew up petitions demanding immediate payment from Adams.

Finally, in 1772, the court decided the funds could not be collected in full and accepted the small amount Adams did raise, mostly borrowed money for his friend John Hancock, and wrote off the rest.

According to the book The Founding of a Nation, Tax commissioner Andrew Oliver accused Adams of embezzlement and suggested he only escaped punishment by convincing Hancock to help him:

“in the same manner that the Devil is represented seducing Eve, by constant whispering at his ear…” which allowed him to “commit his ravages on the government until he undermined the foundations of it, and not one stone had been left upon another.”

Despite his enemies best efforts, Adams continued with his political activities, such as organizing the Boston Tea Party, and later became Governor of Massachusetts in 1794.

Sources:

Irvin, Benjamin. Samuel Adams: Son of Liberty, Father of Revolution. Oxford University Press, 2002

Miller, John C. Sam Adams: Pioneer in Propaganda. Stanford University Press, 1936

Jensen, Merrill. The Founding of a Nation: a History of the American Revolution, 1763-1776. Hackett Publishing Company, Inc, 1968