On April 30, 1844, Henry David Thoreau accidentally started a major forest fire in the Concord woods after his campfire got out of control. The fire burned 300 acres of forest and nearly set the town of Concord ablaze.

The local newspaper, The Concord Freeman, estimated the damages at over $2,000 and chided Thoreau, indirectly, for his “thoughtlessness.”

Thoreau recounted the event in a long journal entry, dated May 31, 1850, during which he explained why he didn’t feel any remorse for starting the fire:

“I once set fire to the woods. Having set out, one April day, to go to the sources of Concord River in a boat with a single companion, meaning to camp on the bank at night or seek a lodging in some neighboring country inn or farmhouse, we took fishing tackle with us that we might fitly procure our food from the stream, Indian-like.

At the shoemaker’s near the river, we obtained a match, which we had forgotten. Though it was thus early in the spring, the river was low, for there had not been much rain, and we succeeded in catching a mess of fish sufficient for our dinner before we had left the town, and by the shores of Fair Haven Pond we proceeded to cook them.

The earth was uncommonly dry, and our fire, kindled far from the woods in a sunny recess in the hillside on the east of the pond, suddenly caught the dry grass of the previous year which grew about the stump on which it was kindled. We sprang to extinguish it at first with our hands and feet, and then we fought it with a board obtained from the boat, but in a few minutes it was beyond our reach; being on the side of a hill, it spread rapidly upward through the long, dry, wiry grass interspersed with bushes….

As I ran toward the town through the woods, I could see the smoke over the woods behind me marking the spot and the progress of the flames…

Presently I heard the sound of the distant bell giving the alarm, and I knew that the town was on its way to the scene. Hitherto I had felt like a guilty person — nothing but shame and regret. But now I settled the matter with myself shortly. I said to myself, ‘Who are these men who are said to be the owners of these woods, and how am I related to them? I have set fire to the forest, but I have done no wrong therein, and now it is as if the lightning had done it. These flames are but consuming their natural food.’

It has never troubled me from that day to this more than if the lightning had done it. The trivial fishing was all that disturbed me and disturbs me still. So shortly I settled it with myself and stood to watch the approaching flames. It was a glorious spectacle and I was the only one there to enjoy it. The fire now reached the base of the cliff, and then rushed up its sides. The squirrels ran before it in blind haste, and three pigeons dashed into the midst of the smoke. The flames flashed up the pines to their tops, as if they were powder…

It burned over a hundred acres or more and destroyed much young wood. When I returned home late in the day, with others of my townsmen, I could not help noticing that the crowd who were so ready to condemn the individual who had kindled the fire did not sympathize with the owners of the wood, but were in fact highly elate and as it were thankful for the opportunity which had afforded them so much sport, and it was only half a dozen owners so called, though not all of them, who looked sour or grieved, and I felt that I had a deeper interest in the woods, knew them better, and should feel their loss more, than any or all of them…

Some of the owners, however, bore their loss like men, but other some declared behind my back that I was a ‘damned rascal;’ and a flibbertigibbet or two, who crowed like the old cock, shouted some reminiscences of ‘burnt woods’ from safe recesses for some years after. I have had nothing to say to any of them…I at once ceased to regard the owners and my own fault, — if fault there was any in the matter, — and attended to the phenomenon before me, determined to make the most of it. To be sure, I felt a little ashamed when I reflected on what a trivial occasion this had happened, that at the time I was no better employed than my townsmen…”

Although Thoreau wrote that he did not feel any guilt over his actions, the fact that he was still dwelling on the incident, and the attention he received as a result of it, six years later suggests otherwise.

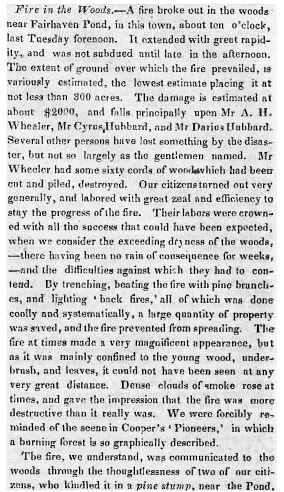

Article in The Concord Freeman about the forest fire set by Henry David Thoreau, circa May 3, 1844

Residents of the town were angry at Thoreau for not only damaging personal property in the fire but also for burning some of the last remaining untouched woodland in an area that had been devastated by deforestation brought on by the industrial revolution.

As Thoreau stated in his journal, the residents continued to taunt him years later, calling him the “woods burner” wherever he went.

Coincidentally enough, a few days after Thoreau described his wood burning incident in his journal, on June 4th he reported that he spent the entire day fighting a fire in the woods and remarked on the sound the fire made as it worked its way through the woods:

“I heard from time to time the dying strain, the last sigh, the fine, clear, shrill scream of agony, as it were, of the trees breathing their last, probably the heated air or the steam escaping from some chink.”

Later that month, he wrote again about the cause and effect of forest fires, stating:

“When the lightening burns a forest its director makes no apology to man, I was but his agent.”

In 2009, Thoreau’s accidental fire was immortalized in a novel by author John Pipkin, titled Woods Burner. The novel suggests that the fire, and Thoreau’s lingering guilt, may have inspired him to build his cabin at Walden Pond just a year later, where he wrote his famous work, Walden, as a way to repay his debt to nature.

Sources:

Wineapple, Brenda. “Consuming Passion.” New York Times, New York Times Company, 1 May. 2009, www.nytimes.com/2009/05/03/books/review/Wineapple-t.html

Pipkin, John. “Woods Burner.” Boston.com, Boston Globe, 12 April. 2009, www.boston.com/bostonglobe/ideas/articles/2009/04/12/woods_burner/

Bergeron, Chris. ” Forest Fire Set by Henry David Thoreau Sparks Illuminating Nove.” Wicked Local, 15 May. 2009, www.wickedlocal.com/easton/fun/entertainment/arts/x1549040002/Forest-fire-set-by-Henry-David-Thoreau-sparks-illuminating-novel#axzz23AB5wr8r

Thoreau, Henry David. The Journal of Henry David Thoreau: 1837-1861. New York Review of Books, 2009

This is wonderful!! I enjoyed reading about Mr. Thoreau so much. What an interesting man.!! I was on This web site looking for the college or school that my Grandfather attended when he was a young man living in Northampton. He became a pharmacist and I wondered where he might have gotten that education in 1902. He was born in 1884 and I thought that 1902 would be about the time he would be getting that education! I love History too, so continue to send me more of these articles. Thank you. I am Janet Turner and now living in Texas. Springfield, Ma. was my home town.

I look forward to more articles. Thank You!!

Thank you, Janet!

A very overrated writer who “lived off the land” with lots of financial help from Emerson. I don’t know anyone I know who attended Concord schools who read or cared much about his “work”.

You’re entitled to your opinion but I strongly disagree. He’s one of my favorite writers and I care very much about his work.

yep

I care very much about Thoreau, but he was clearly only human. This deployment of his immense eloquence and philosophical insight and wisdom in the service of total self-exculpation has always disappointed and mildly alarmed me. Any grievous mistake or crime might be “transcendentalized” away in this fashion, and by refusing to take responsibility and make amends as best he could, Thoreau let down his own best self.