Henry David Thoreau was a writer from Concord, Massachusetts who was a part of the transcendentalist movement in the 19th century.

He is most famous for his book Walden which is about his two-year experience of living in a cabin at Walden Pond in Concord.

Where Was Henry David Thoreau Born?

Henry David Thoreau was born on July 12, 1817 in a farmhouse, known as the Minot house, on Virginia Road in Concord, Mass. Thoreau was actually born David Henry Thoreau but began calling himself Henry David after finishing college, although he never legally changed his name.

Henry David Thoreau’s Family:

Thoreau’s parents were John Thoreau and Cynthia Dunbar. Henry David Thoreau had three siblings: Helen Thoreau, born 1812, John Thoreau, Jr, born 1815, and Sophia Thoreau, born 1819.

John Thoreau, Sr, was the son of a French Protestant immigrant, Jean Thoreau. Jean Thoreau was born at St. Helier, Isle of Jersey, in 1754 and immigrated to America in 1773.

Henry David Thoreau’s maternal family, the Dunbar family, were of English descent, according to the book The Personality of Thoreau:

“On the Thoreau side they were French and English, – the two races having mingled in the Channel Islands – with a sprinkling of Scotch ancestry; while on the Dunbar side they were Scotch and English, filtered through many generations of New England colonists, some of whom took the English or Tory side in the Revolution of Washington and the Adamses.”

A close friend of Henry David Thoreau, fellow writer William Ellery Channing, wrote in his 1871 biography of his friend, titled Thoreau: The Poet-naturalist, that Thoreau sometimes spoke with a faint French accent, which Channing suggested was due to his French ancestry:

“Henry retained a peculiar pronunciation of the letter r, with a decided French accent. He says, ‘September is the first month with a burr in it’; and his speech always had an emphasis, a burr in it. His great-grandmother’s name was Marie le Galais; and his grandfather, John Thoreau, was baptized April 28, 1754, and took the Anglican sacrament in the parish of St. Helier (Isle of Jersey), in May, 1773. Thus near to old France and the Church was our Yankee boy.”

The Thoreau family left the farm where Henry David was born when he was about a year old and moved to Chelmsford, Mass for two years and then moved to Boston for three years before finally returning to Concord.

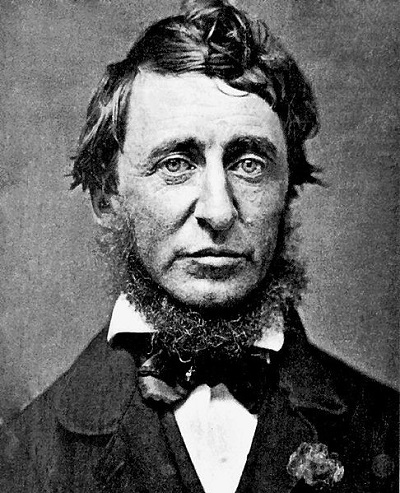

Henry David Thoreau circa 1856

In Channing’s biography of Thoreau, Channing relayed some stories of Thoreau’s early years told by his mother, which describe him as an adventurous young boy often plagued by injury and a chronic health condition:

“At Chelmsford he was tossed by a cow, and again, by getting at an axe without advice, he cut off a good part of one of his toes; and he once fell from a stair. After this last achievement, as after some others, he had a singular suspension of breath, with a purple hue in his face, – owing, I think, to his slow circulation (shown in his slow pulse through life) and hence the difficulty of recovering his breath. Perhaps a more active flow of blood might have afforded an escape from other and later troubles.”

Henry David Thoreau’s family struggled financially until Henry’s Uncle Charlie stumbled upon a graphite mine in New Hampshire in 1821. Charlie put a claim in on the mine and he and Thoreau’s father went into business together using the graphite to make pencils.

After Charlie lost interest and dropped out of the business it became the John Thoreau & Co. The pencils were high acclaimed and won awards for their high quality, bringing the Thoreau family financial stability.

Henry David Thoreau’s Childhood and Early Life:

Thoreau attended an overcrowded public grammar school in Concord before entering Concord Academy with his brother John in 1828.

When Thoreau wasn’t in school, he was outside exploring nature and taking long walks in the woods and fields with his parents, who were also nature lovers. Thoreau’s friend, Horace Hosmer believed Thoreau’s love of nature came from his parents.

According to the book Henry David Thoreau: A Biography, Thoreau was a bit of a loner as a child and spent most of his time outdoors:

“Henry was a good student, but not a mixer. He stood aside and watched when the others played games. Even when the townsfolk turned out for street parades and the rollicking music of bands, he would stay home. He liked to watch the canal barges move along the Concord River, loaded with bricks or iron ore, and was thrilled when the boatmen let him leap aboard for a short passage. A special treat came when his mother asked him to stay home from school to pick the huckleberries she needed for a pudding. With her love of nature, she tried to open her children to its delight. Growing up in the countryside, Henry would have come to know every bug, bird, berry, and beast, every fruit and flower.”

According to Channing, Thoreau’s mother described her son as a very serious and thoughtful young boy:

“I have heard many stories related by his mother about these early years; she enjoyed not only the usual feminine quantity of speech, but thereto added the lavishness of age. Would they had been better told, or better remembered! For my memory is as poor as was her talk perennial. He was always a thoughtful, serious boy, in advance of his years, – wishing to have and do things his own way, and ever fond of wood and field; honest, pure, and good; a treasure to his parents, and a fine example for less happily constituted younglings to follow. Thus Mr. Samuel Hoar gave him the title of ‘the judge’ from his gravity, and the boys at the town school used to assemble about him as he sat on the fence, to hear his account of things.”

Thoreau had a knack for mechanics and construction. According to Channing, when sudden rain storms would threaten his walks in the woods, Thoreau could build a makeshift shelter in a matter of minutes with nothing more than a knife.

Thoreau also built his own boat, at age 16, which he called “the Rover” and used it to row along the Concord river, then built another boat with his brother John, which he used on his trip up the Merrimack River in his book A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers. In addition to boats, Thoreau also made pencils, built fences, finished barns and built bookcases.

After finishing his final year at Concord Academy in 1833, Thoreau reluctantly began to prepare to go to Harvard University. Although his father suggested he become an apprentice to a carpenter or cabinet-maker, his mother insisted that he get the best education he could. He took the entrance exams that summer and barely passed.

Tuition to Harvard at the time was $55 a year and with textbooks and room and board it came to $179. This was more than his parents could afford so his entire family, including his siblings and two aunts, pitched in to help.

While at Harvard, Thoreau studied multiple languages and sat in on lectures on German literature by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. At the time, Harvard allowed students to take 13 weeks off from school in order to teach and earn money for tuition. From December of 1835 to March of 1836, Thoreau taught students at a school in Canton, Mass.

In May of 1836, Thoreau became ill with what historians now believe was his first bout of tuberculosis. He became so weak and exhausted that he couldn’t return to Harvard. He spent the summer building a new boat, which he named Red Jacket, and took a trip to New York with his father to sell their pencils to local stores.

Thoreau returned to college in the fall but was frequently plagued by illness. He made it through his senior year and graduated with a bachelor of arts on August 30, 1837.

After graduating, Thoreau returned to Concord and took a job as a teacher at the public grammar school he attended as a child. The job only lasted two weeks though because he refused to use corporal punishment to control the children in his class. After being pressured to punish some of the more unruly children, he did so and then promptly quit his job that evening.

Thoreau tried to find work in other schools but an economic depression had begun in the U.S., triggered by the panic of 1837, and there were few jobs to be found. To make ends meet, Thoreau took a job in his father’s pencil factory and used his knack for construction and his love of reading to find a new way to improve the pencils, which led to a surge in sales.

Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau:

Some sources say Thoreau first met Emerson in February of 1835 at Harvard where Emerson was giving a lecture, but the two were not close friends yet.

In the fall of 1837, Thoreau became more casually acquainted with Emerson, whose book, Nature, Thoreau had read at Harvard and greatly admired. This casual acquaintance would soon develop into a close friendship, according to the book Henry David Thoreau: A Biography:

“In some ways, Emerson became a substitute father for Thoreau. It was to Emerson that Thoreau looked for guidance. They shared books and the ideas opening out from them. In Emerson’s home, Thoreau could meet young and gifted people from all over the country and from abroad too.”

It was through Emerson that Thoreau met many other Concord writers such as Nathaniel Hawthorne, William Ellery Channing and Louisa May Alcott.

It was in October of 1837 that Emerson suggested to Thoreau that he keep a journal. Thoreau took his mentor’s advice and wrote his first journal entry on October 22, 1837. He continued writing in his journal for the rest of his life, writing over two million words that eventually filled up about 14 volumes. These journals were later published after his death.

In the fall of 1838, Thoreau opened his own private school with his brother John. It was first held in their own home but then moved to the deserted building of the Concord Academy. It was a coeducational school made up of local students as well as children from out of town who boarded with the Thoreau family. One of its many students was a young Louisa May Alcott who began attending the school in 1840 when she first moved to Concord with her family.

Advertisement for Henry David Thoreau’s Concord Academy, published in the Yeoman’s Gazette, circa 1838

The school didn’t use physical punishment and adopted new and radical educational methods. Henry taught language and sciences while his brother John taught English and math.

The Thoreau brothers took their students on frequent field trips to the local fields, woods and ponds as well as to the local businesses, such as the newspaper office and the gunsmith, to learn how they operated. The school earned such a great reputation that there was soon a waiting list to enroll.

During the summer of 1839, Henry and John built a boat and sailed up the Merrimack River to the White Mountains of New Hampshire for a two week trip. The two slept on buffalo skins in a cotton tent, hiked in the woods and climbed Mount Washington.

The trip made such an impact on Thoreau that it became the basis of his first book, A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, which he published in 1849.

That summer, the Thoreau brothers also met a young woman named Ellen Sewall, whom they both fell in love with, according to the book Henry David Thoreau: A Biography:

“Thoreau fell in love at least once. He lost his heart to Ellen Sewall, the sister of his pupil Edmund Sewall. In July 1839, when Ellen was seventeen and Thoreau twenty-three, she visited Concord, staying with the Thoreau family for two weeks. Both Henry and John were charmed by the beautiful girl. She went walking and boating with the brothers, and by the time she left, they were both in love with her.”

The following year, in November of 1840, they both proposed to her, first John and then Henry. Sewall at first accepted John’s proposal, but upon realizing that it was Henry that she actually had feelings for, she broke off the engagement.

Henry then proposed and, upon conferring with her father, a minister who disapproved of both Thoreau brothers as a suitable match, she informed Henry that she could not marry him.

A few years later, Sewall married a young minister named Joseph Osgood. Various sources say that both Ellen and Henry still had feelings for each other for the rest of their lives.

Thoreau soon began to publish his writing more and more around this time. He began to give lectures at the Concord Lyceum and also published poems and essays in Emerson’s transcendentalist newsletter The Dial.

When John Thoreau, Jr, became ill in 1841, Henry David couldn’t continue their school on his own and closed it down in April. Henry David Thoreau was invited to live with Ralph Waldo Emerson and his family at their house where Thoreau did odd jobs in exchange for room and board.

On New Years day in 1842, John Thoreau cut his finger while shaving and soon became sick with tetanus and lock jaw. He died 11 days later in his brother’s arms. Thoreau was sick with grief and soon begin to exhibit symptoms of lockjaw himself although he hadn’t received a cut. He recovered a few days later but was depressed for months. Many historians believe he was exhibiting symptoms of a psychosomatic illness.

In September of 1842, Thoreau met Nathaniel Hawthorne and his wife Sophia Peabody, who had just moved to Concord and were renting the Old Manse from the Emerson family. Hawthorne mentioned meeting Thoreau in his journal the following day:

“Mr. Thorow [sic] dined with us yesterday. He is a singular character—a young man with much of wild original nature still remaining in him; and so far as he is sophisticated, it is in a way and method of his own. He is as ugly as sin, long-nosed, queer-mouthed, and with uncouth and somewhat rustic, although courteous manners, corresponding very well with such an exterior. But his ugliness is of an honest and agreeable fashion, and becomes him much better than beauty. On the whole, I find him a healthy and wholesome man to know.”

Thoreau and Hawthorne quickly became friends and Thoreau sold him one of his rowboats for seven dollars and took him out on the Concord River to teach him how to operate it.

In May of 1843, Thoreau took a job tutoring one of Emerson’s relatives in Staten Island, New York. He hoped to make connections with editors and publishers in New York but made little headway and by the fall he was so homesick for Concord that he resigned, returned home and went back to work at his father’s pencil factory.

In April of 1844, Thoreau accidentally started a forest fire in Concord while on a camping trip on the Sudbury River with his friend Edward Hoar, son of local Judge Samuel Hoar. The fire occurred when the two came ashore to make a camp fire and cook some fish they had just caught when a stray spark from the fire set the dead grass on fire.

The flames quickly spread up the hill and were soon out of control. The two men ran for help but it was too late. More than 300 acres burned resulting in two thousand dollars worth of damage to three local landowners.

The local newspaper reported on the fire and chided the “thoughtlessness of two of our citizens” for causing the blaze. The paper didn’t identify the men but because Concord was such a small town, word got around that it was Thoreau and Hoar. Thoreau later wrote in his journal that for years after the incident the locals harassed him by calling out “burnt woods” wherever he went.

Henry David Thoreau at Walden Pond:

In the mid 1840s, Thoreau spent two years living in a small cabin at Walden Pond as an “experiment in simplicity.”

Thoreau began building his cabin at Walden Pond in March of 1845 and moved in a few months later on July 4. The cabin was built on the edge of 14 acres of land owned by Ralph Waldo Emerson on the northwestern shore of Walden Pond.

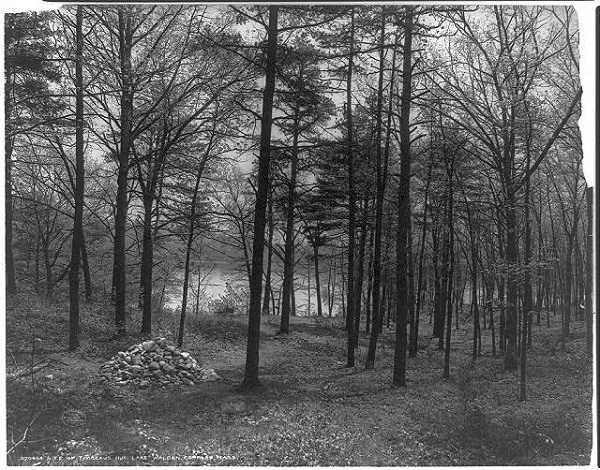

Site of Henry David Thoreau’s Cabin at Walden Pond circa 1908

Thoreau built the small cabin himself. He was highly skilled at construction and had recently gained some house building experience when he helped his father build his house on Texas road the year before, according to Channing:

“In the year before he build for himself this only true house of his, at Walden, he assisted his father in building a house in the western part of Concord Village, called ‘Texas.’ To this spot he was much attached, for it commanded an excellent view, and was retired; and there he planted an orchard. His own house is rather minutely described in his ‘Walden.’ It was just large enough for one, like the plate of boiled apple pudding he used to order of the restaurateur, and which, he said, constituted his invariable dinner in a jaunt to the city. Two was one too much in his house. It was a larger coat and hat – a sentry-box on the shore, in the wood of Walden, ready to walk into in rain or snow or cold. As for its being in the ordinary meaning a house, it was so superior to the common domestic contrivances that I do not associate it with them. By standing on a chair you could reach into the garret, a corn broom fathomed the depth of the cellar. It had no lock to the door, no curtain to the window, and belonged to nature nearly as much as to man. It was a durable garment, an overcoat, he had contrived and left by Walden, convenient for shelter, sleep or meditation.”

On July 6, just a few days after arriving at Walden, Thoreau explained in his journal why he came to live at Walden Pond:

“I wish to meet the facts of life – the vital facts, which are the phenomena or actuality the gods meant to show us – face to face, and so I came down here. Life! Who knows what it is, what it does? If I am not quite right here, I am less wrong than before; and now let us see what they will have.”

Thoreau later reiterated this sentiment in his now famous book Walden:

“I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived. I did not wish to live what was not life, living is so dear; nor do I wish to practice resignation, unless it was quite necessary.”

According to an article, titled Life and Legacy, on the Thoreau Society website, Thoreau went to Walden for two explicit reasons:

“He had two main purposes in moving to the pond: to write his first book, A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, as a tribute to his late brother John; and to conduct an economic experiment to see if it were possible to live by working one day and devoting the other six to more Transcendental concerns, thus reversing the Yankee habit of working six days and resting one. His nature study and the writing of Walden would develop later during his stay at the pond. He began writing Walden in 1846 as a lecture in response to the questions of townspeople who were curious about what he was doing out at the pond, but his notes soon grew into his second book.”

While living at Walden, Thoreau studied nature, kept up his journal and completed a draft of his first book A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers. He grew beans in a field near his house and took odd jobs as a carpenter, mason and surveyor to earn money for the things he could not “grow or make or do with out.”

In July of 1846, while living at Walden, Thoreau was arrested by the local sheriff for failure to pay a poll tax. The poll tax was actually a local tax but Thoreau believed it was a federal tax used to fund the Mexican-American war, which he opposed, and had stopped paying it in 1842 in protest.

Although Thoreau hadn’t paid the tax in four years, the sheriff was slow to respond to this and didn’t even arrest Thoreau until that summer after Thoreau came into town one day to have his shoes repaired.

Thoreau was jailed but was released the next day when an unidentified person came to the jail to pay his debt. This angered Thoreau because he had hoped to use the opportunity to raise awareness to his cause.

Nonetheless, he reluctantly left his jail cell. The experience later inspired Thoreau to write his essay Resistance to Civil Government, which was later renamed Civil Disobedience, in which he argues that it is sometimes necessary to disobey the law in order to protest unjust government actions.

Thoreau left Walden Pond in the autumn of 1847 and moved in to Emerson’s house to help care for his family while Emerson was away in Europe. Thoreau gave his Walden cabin to Emerson who then sold it to his gardener.

A couple of years later, two farmers bought it and moved it to the other side of Concord to store grain in it. In 1868, the farmers dismantled the house for the lumber and put the roof on an outbuilding.

Thoreau continued writing and, in 1849, published his first book, A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, which chronicled his boat trip to the White Mountains with his brother in 1839. He had to pay for the publishing costs himself and when the book didn’t sell, his publisher, James Munroe of Boston. returned the remaining seven hundred copies to Thoreau.

This prompted Thoreau to hold off on publishing Walden so he could revise it and avoid another failure, according to the Thoreau Society website:

“In the years after leaving Walden Pond, Thoreau published A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers (1849) and Walden (1854). A Week sold poorly, leading Thoreau to hold off publication of Walden, so that he could revise it extensively to avoid the problems, such as looseness of structure and a preaching tone unalleviated by humor, that had put readers off in the first book. Walden was a modest success: it brought Thoreau good reviews, satisfactory sales, and a small following of fans.”

About five years later, in 1854, Thoreau finally published Walden, Or Life in the Woods. The book was a moderate success during his lifetime and garnered many positive reviews. It was these reviews that seem to have established Thoreau’s image as an eccentric loner when they described Thoreau as a “hermit” and a “human oddity.”

Nonetheless, in the same breath, the reviewers also often described him as a “genius” and described the book as both “original and refreshing” as can be seen in this review published in the Boston Daily Bee on August 9, 1854:

“An original book, this, and from an original man, – from a very eccentric man. It is a record of the author’s life and thoughts while he lived in the woods – two years and two months. It is a volume of interest and value – of interest because it concerns a very rare individual, and of value because it contains considerable wisdom, after a fashion. It is a volume to read once, twice, thrice – and then think over. There is a charm in its style, a philosophy in its thought. Mr Moreau [sic] tells us of common things we know, but in an uncommon manner. There is much to be learned from this volume. Stearn [sic] and good lessons in economy; contentment with a simple but noble life, and all that, and much more. The author ‘lived like a king’ on ‘hoe cakes’ and drank water; at the same time outworking the lustiest farmers who were pitted against him. Get the book. You will like it. It is original and refreshing; and from the brain of a live man.”

Although successful, it took five years for Walden to sell 2,000 copies and it was out of print by the time Thoreau died less than a decade later.

In 1858, Thoreau became embroiled in a feud with James Russell Lowell, a Boston writer, diplomat and editor of the Atlantic Monthly Magazine, after Lowell published Thoreau’s essay “Chesuncook” and omitted a line about the immortality of a pine tree.

Thoreau apparently became angry when he discovered it and sent Lowell a fiery letter and refused to contribute to the magazine while Lowell was still editor. This feud continued even after Thoreau’s death a few years later when Lowell published an essay attacking the deceased writer.

In the summer of 1858, Thoreau embarked on a walking tour of Cape Ann with his friend John Russell of Salem. While on the journey, Russell and Thoreau visited Dogtown, an abandoned ghost town in Gloucester, Mass and remarked how the great boulders that dotted the landscape “was the most peculiar scenery of the Cape.”

Thoreau also took a month long trip to the midwest in the summer of 1861 and explored the area around the Twin Cities in Minnesota with his friend Horace Mann, Jr. It was the last trip outside of Massachusetts that Thoreau would ever take.

How Did Henry David Thoreau Die?

One night in December of 1860, Thoreau, who had been plagued by tuberculosis for years, got caught in a rainstorm while counting the rings on a tree stump and he became ill with bronchitis.

His health began to decline and, although he had brief periods of remission, he eventually became bedridden. He spent his last years revising and editing his work and continued to write letters and journal entries until he became too weak.

Thoreau died of tuberculosis on May 6, 1862. His last words were “moose” and “Indian.”

At his funeral, Emerson gave the eulogy, Amos Bronson Alcott read selections of Thoreau’s work and Channing presented a hymn, according to the Thoreau Society website:

“In May 1862, Thoreau died of the tuberculosis with which he had been periodically plagued since his college years. He left behind large unfinished projects, including a comprehensive record of natural phenomena around Concord, extensive notes on American Indians, and many volumes of his daily journal jottings. At his funeral, his friend Emerson said, ‘The country knows not yet, or in the least part, how great a son it has lost. … His soul was made for the noblest society; he had in a short life exhausted the capabilities of this world; wherever there is knowledge, wherever there is virtue, wherever there is beauty, he will find a home.’”

Where is Henry David Thoreau Buried?

Thoreau was buried in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Concord, Mass. He was originally buried in the Dunbar family plot in the lower half of the cemetery, but his grave was relocated in 1870 to Author’s Ridge towards the back of the cemetery to be closer to the graves of his writer friends Emerson, Alcott, Hawthorne and Channing.

Henry David Thoreau’s grave, Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, Concord, Mass, in 2013. Photo credit: Rebecca Beatrice Brooks

Books and Essays by Henry David Thoreau:

Books:

A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, James Munroe and Company, 1849

Walden; or, Life in the Woods, Ticknor and Fields, 1854

Excursions, Ticknor and Fields, 1863

The Maine Woods, Ticknor and Fields, 1864

Cape Cod, Ticknor and Fields, 1865

A Yankee in Canada, with Anti-Slavery and Reform Papers, Ticknor and Fields, 1866

Essays:

Aulus Persius Flaccus, The Dial, July 1840

Natural History of Massachusetts, The Dial, July 1842

Homer, Ossian, Chaucer, The Dial, January 1843

A Walk to Wachusett. The Boston Miscellany, January 1843

Dark Ages, The Dial, April 1843

A Winter Walk, The Dial, October 1843

The Landlord, The United States Magazine and Democratic Review, October 1843

Herald of Freedom, The Dial, April 1844

Thomas Carlyle and His Works, Graham’s Magazine, serialized in two installments, March 1847, April 1847

Ktaadn and the Maine Woods, Sartain’s Union Magazine, serialized in five installments: The Wilds of the Penobscot. July 1848, Life in the Wilderness, August 1848, Boating in the Lakes, September 1848, The Ascent of Ktaadn, October 1848, The Return Journey, November 1848

Resistance to Civil Government, 1849, Civil Disobedience, 1866, Aesthetic Papers, May 1849

The Iron Horse, Sartain’s Union Magazine, July 1852

A Poet Buying a Farm, Sartain’s Union Magazine, August 1852

An Excursion to Canada, Putnam’s Magazine, serialized in three installments, January 1853, February 1853, March 1853

A Massachusetts Hermit, New York Daily Tribune, March 29,1854

Slavery in Massachusetts, The Liberator, July 21, 1854

Cape Cod, Putnam’s Magazine, serialized in four installments: The Shipwreck, June 1855, Stage Coach Views, June 1855, The Plains of Nanset [sic], July 1855, The Beach, August 1855

Chesuncook, The Atlantic Monthly, serialized in three installments: June 1858, July 1858, August 1858

The Last Days of John Brown, The Liberator, July 27, 1860

A Plea for Captain John Brown, Included in Echoes of Harpers Ferry, edited by James Redpath, Thayer and Eldridge, 1860

An Address on the Succession of Forest Trees,Transactions of the Middlesex Agricultural Society for the Year 1860

Walking, The Atlantic Monthly, June 1862

Autumnal Tints, The Atlantic Monthly, October 1862

Wild Apples, The Atlantic Monthly, November 1862

Life Without Principle, The Atlantic Monthly, October 1863

Night and Moonlight, The Atlantic Monthly, November 1863

The Wellfleet Oysterman, The Atlantic Monthly, October 1864

The Highland Light, The Atlantic Monthly, December 1864

The Service, Edited by F. B. Sanborn, Charles E. Goodspeed, 1902

Henry David Thoreau Historical Sites:

Thoreau Farm: Birthplace of Henry David Thoreau

Website: thoreaufarm.org

Address: 341 Virginia Road, Concord, Mass

Walden Pond State Reservation

Website: mass.gov/eea/agencies/dcr/massparks/region-north/walden-pond-state-reservation.html

Address: 915 Walden Street, Concord, Mass

Henry David Thoreau’s Grave

Sleepy Hollow Cemetery

Address: 34 Bedford St B, Concord, Mass

Sources:

Sanborn, Franklin Benjamin. The personality of Thoreau. Charles E. Goodspeed, 1901.

Meltzer, Milton. Henry David Thoreau: A Biography. Twenty-First Century Books, 2007.

Channing, William Ellery. Thoreau, the poet-naturalist. Charles E. Goodspeed, 1902.

Dean, Bradley P. and Gary Scharnhorst. “The Contemporary Reception of Walden.” Studies in the American Renaissance, 1990, pp: 293-328.

“Life and Legacy.” The Thoreau Society, thoreausociety.org/life-legacy

“The Actual Journey.” Henry David Thoreau’s Journey West, Corrine H, Smith, thoreausjourneywest.com/journey.htm

“Thoreau at Walden Pond.” Mass.gov, Commonwealth of Massachusetts, mass.gov/eea/agencies/dcr/massparks/region-north/thoreau-at-walden-pond-reservation.html

“Concord Chronology.” Washington State University, public.wsu.edu/~campbelld/amlit/concord.htm

“Reflections on Walden.” The Writings of Henry David Thoreau, thoreau.library.ucsb.edu/thoreau_walden.html

“The Family Tree of Henry David Thoreau.” The Thoreau Society, thoreausociety.org/life-legacy/family-tree

“Henry David Thoreau.” The Walden Woods Project, walden.org/thoreau

Schneider, Richard J. “Thoreau’s Life.” The Thoreau Society, thoreausociety.org/life-legacy

Hi, I wanted to bring to your attention there are Henry David Thoreau Forever Stamps available.

With this stamp, the U.S. Postal Service® celebrates writer, philosopher, and naturalist Henry David Thoreau (1817–1862).

For more information, please visit the Postal Store® at http://www.usps.com or call (800) 782-6724.