Anne Hutchinson was a Puritan religious leader and midwife who moved from England to the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1634.

The following are some facts about Anne Hutchinson:

Hutchinson was born Anne Marbury in Alford, Lincolnshire, England on July 20, 1591 and was the daughter of Bridget Dryden and Francis Marbury, a Deacon in the Church of England.

Francis Marbury was a dissident minister who had been silenced and imprisoned many times for complaining about the poor training of English clergymen.

Anne Hutchinson’ Childhood & Early Life:

As a child, Anne had been deeply influenced by her rebellious father and his own troubles with the church left a big impression on her, according to the book “American Jezebel”:

“Although entirely without formal schooling, like virtually every woman in her day, Anne Hutchinson had been well educated on her father’s knee. Francis Marbury, a Cambridge-educated clergyman, school-master, and Puritan reformer, was her father. In the late 1570s, more than a decade before her birth, his repeated challenges to Anglican authorities led to his censure, his imprisonment for several years, and his own public trial – a on a charge of heresy, the same charge that would be brought against his daughter, of refuting church dogma or religious truth. Marbury’s trial was held in November 1578 at Saint Paul’s Cathedral in London, fifty-nine years and an ocean distant from her far better known trial. His trial left an abiding mark on her, though, and its themes foreshadowed those of hers. During a lengthy period of church-imposed house arrest that coincided with Anne’s first three years of life, her father composed from memory a biting transcription of his trial, which he called ‘The conference between me and the Bishop of London’ with ‘many people standing by.’ This dramatic dialogue, published in the early 1590s as a pamphlet, was one of the central texts he used to educate and amuse his children.”

On August 9, 1612, Anne married William Hutchinson, a London merchant, with whom she eventually had 15 children.

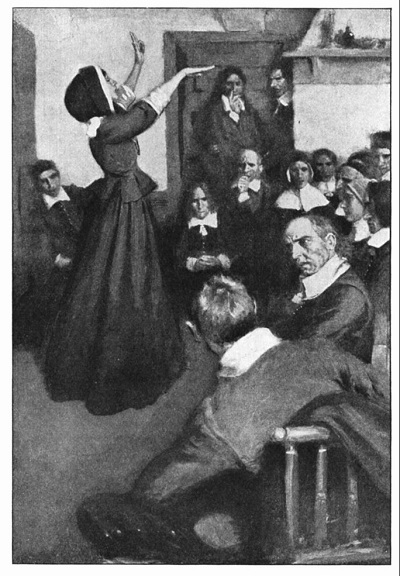

“Anne Hutchinson Preaching in Her House in Boston,” illustration published in Harper’s Monthly, circa February 1901

The couple moved back to Alford and began attending the services of a new preacher, Reverend John Cotton, at St. Botolph’s in Boston, Lincolnshire.

Anne was instantly mesmerized by Cotton and the two began a mentor-type relationship. Under his guidance, Anne led weekly prayer meetings in her home.

After John Cotton went into hiding when he was threatened with imprisonment for his views, he fled England for the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1633.

Anne Hutchinson in the Massachusetts Bay Colony:

Feeling lost without her mentor, Anne then convinced her husband that they should follow Cotton to the New World. William consented and the Hutchinsons arrived in the Massachusetts Bay Colony on September 18, 1634.

As a wealthy and prominent cloth merchant, William bought a half-acre lot on the Shawmut peninsula, in what is now downtown Boston, and built a large timber frame two-story house on the exact spot where the Old Corner Bookstore building now stands.

William Hutchinson continued his cloth business and Anne became a midwife, often giving spiritual advice to the mothers she assisted.

Things went well for both Cotton and the Hutchinsons until 1636, when they started speaking out against the way Puritans leaders were being trained, thus sparking the Antinomian Controversy, a religious and political conflict that lasted until 1638, according to the book “Rebels and Renegades: A Chronology of Social and Political Dissent in the United States”:

“Soon after Cotton began complaining that the Puritan ministers in Massachusetts Bay were emphasizing the covenant of works, Hutchinson began holding meetings at her house. Initially, she merely led discussions relating to Cotton’s sermons. Later, rumors circulated that she had accused the ministers of teaching only the covenant of works. Such an accusation assaulted the heart of the Puritan beliefs, that faith mattered most. To accuse the Puritan ministers of teaching a covenant of works was to accuse them of being no better than the Church of England, against which the Puritan movement had originally begun as an alternative to Anglican ‘faithlessness.’ Hutchinson’s charge struck at the power of the colony’s leaders: the ministers did not hold public office, but they wielded enormous political power and to portray them as being on the wrong path implied they should be replaced. Consequently, her claims divided the Puritan community, and in 1636 those who supported her succeeded in electing Henry Vane as the colony’s governor. Vane, the 24-year-old son of a British government official, had attended Hutchinson’s meetings.”

This victory was short lived since the orthodox Puritans defeated Vane in the next election and elected John Winthrop as Governor.

Feeling pressure to maintain conformity in the colony, Winthrop and his colleagues met in August of 1637 and decided to find a way to discredit and denounce Hutchinson. Incidentally, it was during this meeting that the religious leaders first discussed the idea of the New England Confederation, which was an alliance between the New England colonies.

First the religious leaders decided to disenfranchise and ban Anne’s prominent friends and allies and then they charged Hutchinson with sedition, the act of inciting people to rebel against authority.

The fact that Hutchinson’s charge of sedition was against the ministers, not the civil magistrates, demonstrates the lack of separation between church and state and suggests that if you undermine one, you undermine the other as well.

Old Corner Bookstore, Boston, Ma, circa 19th century, former site of Anne Hutchinson’s house

Hutchinson found herself in more trouble in October of 1637, about a month before her trial began, when she assisted in Mary Dyer’s birth of what the Boston ministers would later call a “monster.” Dyer’s baby was a stillborn with anencephaly and spina bifada malformations.

Knowing the controversy the birth would create, Hutchinson wrapped the baby in a blanket in an attempt to conceal its deformities and buried it in unconsecrated ground, most likely somewhere on Boston Common.

Winthrop and others eventually learned of the birth and exhumed the corpse. Upon examining it, the Boston ministers declared the deformed baby a punishment from God, just as they did later when Hutchinson endured a similar delivery herself in 1638, and viewed Hutchinson guilty by association for her role in the birth.

Anne Hutchinson’s Trial:

Hutchinson was brought to trial for sedition on November 7, 1637. During her trial, Hutchinson, who was possibly pregnant at the time (many historians aren’t sure if she became pregnant before or after her trial), underwent intense questioning.

Winthrop accused her of violating the 5th commandment to “honor they father and thy mother,” implying that she had defied authority. He also criticized her for teaching men, which was a violation of the Puritan’s rule that women should not be leaders.

Her testimony, during which she proudly professed to violating many Puritan rules, was the most damning, according to the book “Rebels and Renegades”:

“Hutchinson denied she had ever said the ministers were preaching only the covenant of works. Nevertheless, she said, ‘When they preach a covenant of works for salvation, that is not truth.’ Strong and assertive, Hutchinson made a startling claim in her testimony to the court: ‘I bless the Lord,’ she said. “He hath let me see which was the clear ministry and which the wrong.’

‘How do you know that was the spirit?’ the court asked her.

‘How did Abraham know that it was God that bid him offer his son, being a breach of the sixth commandment?’ she replied.

‘By an immediate voice,’ the court said.

‘So too me by an immediate revelation,’ she responded.

‘How! An immediate revelation ,’ the court said.

‘By the voice of his spirit to my soul,’ she insisted.

Thus Hutchinson had claimed that God had revealed himself directly to her, a stance that violated the Puritan doctrine that revelation ended with the bible. Orthodox Puritans labeled Hutchinson a blasphemer and an antinomian, a person who believed that commands came only from God and that salvation freed an individual from the laws of church and state….Such ideas as Hutchinson’s opened society to potential disorder, should everyone assert that they could determine God’s revelations, and with them, God’s directions, for themselves.”

The court declared her a heretic, banished her from the Massachusetts Bay Colony and ordered her to be gone by the end of March.

Afterward, they placed her under house arrest at the home of Joseph Weld, while she awaited her church trial. It was during this time that her friend and mentor, Reverend John Cotton, turned his back on her, according to an article in Harvard Magazine:

“Having been found guilty in her civil trial, she was placed under house arrest to await ecclesiastical trial. In 1638, the final blows were delivered. A sentence of banishment was never in doubt. Her former mentor, John Cotton, fearing for his own credibility, described her weekly Sunday meetings as a ‘promiscuous and filthie coming together of men and women without Distinction of Relation of Marriage’ and continued, ‘Your opinions fret like gangrene and spread like leprosy, and will eat out the very bowels of religion.'”

Hutchinson’s church trial began on March 15, 1638 at her home church in Boston. During the trial, the church leaders tried to get her to repent and confess her errors but to no avail, according to the book “The Antinomian Controversy”:

“If the trial seems harsh to the modern reader, its role within the Puritan context was punitive only in a limited sense. Punishment by the church was meant to inspire repentance, and a genuine act of repentance could lead to the restoration of church membership. Those who prosecuted Mrs. Hutchinson hoped that she would confess her errors, as, for a moment, she did. But in the end she stood her ground and the church had no other choice then to cast her out.”

Anne Hutchinson on Trial, illustration by Edwin Austin Abbey, circa 1901

The church leaders read the charges against Hutchinson and tried to get her to admit they were errors but she remained defiant, according to court records:

“Mr. Leverit: Sister Hutchinson, here is diverse opinions laid to your charge by Mr. Shephard and Mrs. Frost, and I must request you in the name of the church to declare whether you hold them or renounce them as they be read to you.

1. That the souls of all men by nature are mortal.

2. That those that are united to Christ have two bodies, Christ’s and a new body and you knew not how Christ should be united to our fleshly bodies.

3. That our bodies shall not rise with Christ Jesus, not the same bodies at the last day.

4. That the Resurrection mentioned is not of our resurrection at the last day, but of our union to Jesus Christ.

5. That there be no created graces in the human nature of Christ nor in believers after their union.

6. That you had no scripture to warrant Christ being now in heaven in his human nature.

7. That the Disciples were not converted at Christ’s death.

8. That there is no Kingdom of Heaven but Christ Jesus.

9. That the first thing we receive for our assurance is our election.

These are alleged from Mr. Shepard. The next are from Roxbury.

1. That sanctification can be no evidence of a good estate in no wise.

2. That her revelations about future events are to be believed as well as scripture because the same Holy Ghost did indite both.

3. That Abraham was not in saving estate until he offered Isaac and so saving the firmness of God’s election, he might have perished eternally for any work of grace that was in him.

4. That a hypocrite may have the righteousness of Adam and perish.

5. That we are not bound to the law, not as a rule of life.

6. That not being bound to the law, no transgression of the law is sinful.

7. That you see no warrant in scripture to prove that the image of God in Adam was righteousness and true holiness.

These are alleged against you by Mr. Wells and Mr. Eliot. It is desired by the church, Sister Hutchinson, that you express this be your opinion or not.

Anne: If this be error then it is mine and I ought to lay it down. If this be truth, it is not mine but Christ Jesus’ and then I am not to lay it down. But I desire of the Church to demand one question. By what rule of the word when these elders shall come to me in private to desire satisfaction in some points and do profess in the sight of God that they did not come to entrap nor ensnare me, and now without speaking to me and expressing any dissatisfaction would come to bring it publicly into the Church before they had privately dealt with me? For them to come and inquire for light and afterwards to bear witness against it. I think it is a breach of Church Rule, to bring a thing in public before they have dealt with me in private.”

Although it appeared at times during the trial that Hutchinson did admit to errors and mistakes, she still refused to recant her beliefs and was found guilty and excommunicated.

Anne Hutchinson in Rhode Island:

Hutchinson left Massachusetts for Roger Williams’ settlement in Rhode Island on April 1. Her husband, most of her children and many of her friends had already left the colony months before in order to prepare a place for the group to live.

Accompanying Hutchinson on her long walk to Rhode Island were her remaining children, Mary Dyer and about 60-70 of Hutchinson’s followers, many of whom had been exiled by the court themselves in November for sedition.

The group slept in wigwams they either found along the way or made themselves. The journey took over six days and in the second week of April the group finally reached Aquidneck Island in Rhode Island, where their family and friends had already begun to build a settlement.

That May, Hutchinson went into labor and gave birth to a hydatidiform mole, a mass of tissue that is often the result of sperm fertilizing a blighted egg.

When Winthrop learned of the news, he appeared to take pleasure in her misfortune and wrote to Anne’s doctor, John Clarke, to find out more of the details. He later reported in his journal:

“Mistress Hutchinson being big with child, and growing toward the time of her labour, as others do, she brought forth not one (as Mistress Dyer did) but (which was more strange to amazement) thirty monstrous births or thereabouts, at once, some of them bigger, some lesser, some of one shape, some of another; few of any perfect shape, none at all of them (as far as I could ever learn) of human shape. These things are so strange that I am almost loath to be the reporter of them, lest I should seem to feign…But see how the wisdom of God fitted this judgement to her sin every way, for look – as she had vented misshapen opinions, so she must bring forth deformed monsters. And as [there were] about thirty opinions in number, so many monsters. And as those were public, and not in a corner mentioned, so this is now come to be known and famous over all these churches, and a great part of the world.”

Reverend John Cotton also spoke to his congregation about Hutchinson’s miscarriage, stating it “might signify her error in denying inherent righteousness” and suggested it was a punishment from God for her crimes.

Hutchinson continued to find herself surrounded by political controversy in Rhode Island.

Wealthy merchant William Coddington was elected governor of the Aquidneck Island settlement, which they named Pocasset, but he quickly began to alienate the settlers and was overthrown in April of 1639. Hutchinson’s husband, William, was chosen as the new governor.

Coddington and several others then left the area and established the settlement of Newport. After a year, the two settlements decided to reunite and Coddington became Governor of the island and William Hutchinson was chosen to be one of his assistants.

In February of 1639, Winthrop sent three ministers, Edward Gibbons, William Hibbins and John Oliver, to visit Anne Hutchinson to force her to recant her beliefs. When she refused, they warned her that Massachusetts was poised to take over the colony of Rhode Island and she would no longer be welcome there.

After William Hutchinson died in 1642, realizing her future in Rhode Island was uncertain, Anne Hutchinson moved with her children to New York, to the area that is now Pelham Bay Park, which was then the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam. There they would be out of reach of the Massachusetts Puritans.

In Nathaniel Hawthorne’s 1830 biographical sketch of Hutchinson, titled “Mrs. Hutchinson,” Hawthorne envisioned that Hutchinson found not only peace of mind in New York but also the chance to be the leader she always wanted to be:

“Her final movement was to lead her family within the limits of the Dutch Jurisdiction, where, having felled the trees of virgin soil, she became herself the virtual head, civil and ecclesiastical, of a little colony. Perhaps here she found repose, hitherto so vainly sought. Secluded from all whose faith she could not govern, surrounded by dependents over whom she held an unlimited influence, agitated by none of the turmoltuous billows which were left swelling behind her, we may suppose, that, in the stillness of nature, her heart was stilled.”

Anne Hutchinson’s Death:

Little did Hutchinson know, the Dutch colony was a dangerous place to live at the time due to some bad blood between the local Native American tribes and the colony’s governor Willem Kieft.

Many of the local Native American tribes in New York at the time were unhappy about the Dutch settlement and often tried to persuade the settlers to leave.

Kieft further enraged the tribes by mistreating and deceiving them, such as when he tried to extort “protection” money from the Algonquins, Raritans and Wappinger Indians to keep them safe from the local Mohawk tribe, which Kieft actually controlled and used to terrorize other tribes.

When the other tribes refused to pay and attacked the Dutch colony, Kieft unleashed the Mohawks on them. In 1641, Kieft again tried to persuade the Wappinger Indians to pay by sending the Mohwaks after them.

Failing to realize who was really behind the attacks, the Wappinger Indians appealed to Kieft for help. Kieft responded by sending more Mohawks after them and then some of his own troops to attack them.

Actions such as these eventually sparked a series of events known as Kieft’s War.

“Massacre of Anne Hutchinson,” illustration published in A Popular History of the United States, circa 1878

One of these events occurred in August of 1643, when a party of Siwanoy indians raided the section of New York that Hutchinson lived in and she and six of her children were brutally killed, according to the book “American Jezebel”:

“The Siwanoy warriors stampeded into the tiny settlement above Pelham Bay, prepared to burn down every house. The Siwanoy chief, Wampage, who had sent a warning, expected to find no settlers present. But at one house the men in animal skins encountered several children, young men and women, and a woman past middle age. One Siwanoy indicated that the Hutchinsons should restrain the family’s dogs. Without apparent fear, one of the family tied up the dogs. As quickly as possible, the Siwanoy seized and scalped Francis Hutchinson, William Collins, several servants, the two Annes (mother and daughter), and the younger children—William, Katherine, Mary, and Zuriel. As the story was later recounted in Boston, one of the Hutchinson’s daughters, ‘seeking to escape,’ was caught ‘as she was getting over a hedge, and they drew her back again by the hair of the head to the stump of a tree, and there cut off her head with a hatchet.’”

The bodies were dragged into the house, which was then set on fire.

Hutchinson’s nine-year-old daughter, Susanna, was out picking berries at the time of the attack. She hid from the attackers but was eventually captured and lived with her captors for a few years until she was ransomed back to her family, according to the book “Unafraid: The Life of Anne Hutchinson:”

“When another treaty of peace was finally concluded with the Indians in 1645, one of the articles insisted on was a solemn obligation to restore the daughter of Anne Hutchinson. The Dutch guaranteed that had been offered by the New England friends of the little captive, and the obligation on both sides was fulfilled. Susan was restored to the Dutch – against her will, it is said, since she had learned to like her Indian captors – and she was eventually returned to Rhode Island.”

The reaction in the Massachusetts Bay Colony to Anne Hutchinson’s death was harsh. Winthrop wrote in his journal:

“Thus it had pleased the Lord to have compassion of his poor churches here, and to discover this great imposter, an instrument of Satan so fitted and trained to his service for interrupting the passage [of his] kingdom in this part of the world, and poisoning the churches here…This American Jezebel kept her strength and reputation, even among the people of God, till the hand of civil justice laid hold on her, and then she began evidently to decline, and the faithful to be freed from her forgeries…”

The Reverend Thomas Weld also seemed pleased with Hutchinson’s death and happily wrote to acquaintances in England:

“The Lord heard our groans to heaven, and freed us from our great and sore affliction… I never heard that the Indians in those parts did ever before this commit the like outrage upon any one family or families; and therefore God’s hand is the more apparently seen herein, to pick out this woeful woman…”

Later when it was discovered that the warrior, Wampage, took Anne Hutchinson’s name after her death, calling himself “Anne Hoeck,” it was assumed that he was the one who took her life, since it was customary among Native-Americans to adopt the name of their most notable victim.

In 1654, Wampage even transferred the deed of the Hutchinson’s property to Thomas Pell and listed his name on the document as “Anne Hoeck alias Wampage.”

Anne Hutchinson’s Descendants:

Hutchinson has a number of notable descendants. Her great-great grandson was Thomas Hutchinson, who became the loyalist Governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay during the American Revolution.

Her other descendants include U.S. Presidents George W. Bush, George H. Bush and Franklin D. Roosevelt, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court Melville Weston Fuller, Massachusetts Governor Mitt Romney and Associate Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. Her grandson, Peleg Sanford, became Colonial Governor of Rhode Island.

Eve LaPlante, the author of Hutchinson’s biography “American Jezebel” is also one of Hutchinson’s descendants.

Anne Hutchinson’s Legacy: Why Was Hutchinson Important?

Anne Hutchinson is considered one of the first notable woman religious leaders in the North American Colonies. She fought for religious freedom and openly challenged the male dominated government and church authorities, making her a religious and feminist role model.

A number of local landmarks in New York were later named after Hutchinson. The neighboring land near where Hutchinson lived was named Anne-Hoeck’s neck, the local river was named the Hutchinson and the highway that runs alongside it was named the Hutchinson River Parkway.

In 1922, The Anne Hutchinson Memorial Association and the State Federation of Women’s Clubs erected a statue of Anne Hutchinson, sculpted by artist Cyrus Dallin, in front of the Massachusetts State House in Boston.

In 1987, Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis officially pardoned Anne Hutchinson, therefore revoking her banishment from Massachusetts and clearing her name.

Sources:

King-Rugg, Winnifred. Unafraid: The Life of Anne Hutchinson. Houghton Mifflin Company, 1930.

Hamilton, Neil A. Rebels and Renegades: A Chronology of Social and Political Dissent in the United States. Routledge, 2002.

Randall, Willard Sterne and Nancy Nahra. Forgotten Americans: Footnote Figures Who Changed American History. Da Capo Press, 1998.

LaPlante, Eve. American Jezebel: The Uncommon Life of Anne Hutchinson. Harper Collins Publishers, Inc, 2010.

The Antinomian Controversy, 1636-1638: A Documentary History. Edited by David D. Hall, Duke University Press, 1990.

Bryant, William Cullen. A Popular History of the United States. Vol. I, Charles Scribner’s sons, 1878.

“Anne Hutchinson Arrives in the New World.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, www.history.com/this-day-in-history/anne-hutchinson-arrives-in-the-new-world

Gomes, Peter G. “Anne Hutchinson: Brief Life of Harvard’s Midwife: 1595-1643.” Harvard Magazine, November-December 2002, harvardmagazine.com/2002/11/anne-hutchinson.html

“Anne Marbury Hutchinson.” National Women’s History Museum, www.nwhm.org/education-resources/biography/biographies/anne-marbury-hutchinson/

I love this blog about the History of Massachusetts. My 1st ancestor came over from England in 1620 on mayflower. His name was John Alden. My grandfather name is Avard Spidell. And the Spidells came from Germany. Please keep sending me more information as I find it very interesting.

Through ancestory research, just found out that Anne Hutchinson is my 10th great grand mother, and Susanna is my 9th great grandmother. So PROUD of her love for Jesus, and her desire to call out and make things right! Although, I’m pissed about the massacre and how the men spoke out that it was God’s revenge on her! Thanks for this informative information.

Thanks for this – fascinating. I think of Anne Hutchinson’s amazing, tragic story every time I drive down to the Hutchinson River Parkway.

One of my bucket list items is to get off the Parkway sometime and find Split Rock, the location where tradition says Susanna hid during the 1643 attack. However, I’ve read more recently that this likely isn’t true, as the family didn’t live close enough to Split Rock at the time. Does anyone know for certain?

I live a few minutes from Hutchinson’s Park in the Dorchester/Milton are of Mass. Interesting Biography, the defected births are a little puzzling to say the least..