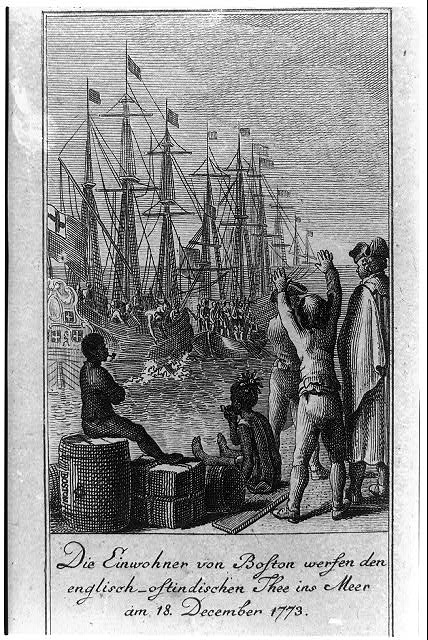

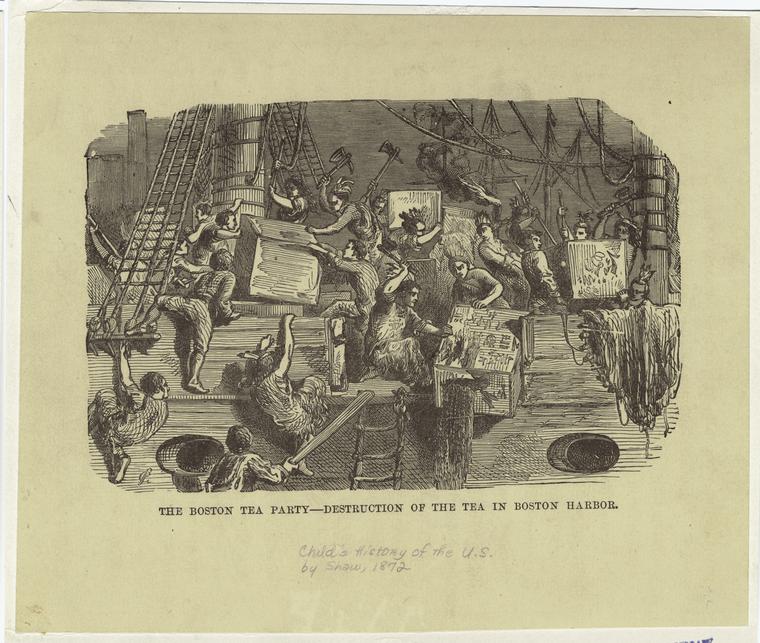

The Boston Tea Party was a pivotal moment in the American Revolution and the British reacted to it with shock.

The day after the Boston Tea Party, John Adams speculated in his diary about how the British would punish the people of Massachusetts and his theories eerily foreshadowed what was to come:

“What Measures will the Ministry take, in Consequence of this?— Will they resent it? will they dare to resent it? will they punish Us? How? By quartering Troops upon Us?—by annulling our Charter?—by laying on more duties? By restraining our Trade? By Sacrifice of Individuals, or how.”

News of the Boston Tea Party finally reached England on January 19, 1774 when it was brought by the ship Hayley.

When King George III learned of the destruction of the tea later that evening, he regarded it merely as a temporary setback instigated by a few hotheads in Boston, as suggested by his comment to Lord Dartmouth:

“I am much hurt that the instigation of bad men hath again drawn the people of Boston to take such unjustifiable steps; but I trust by degrees tea will find its way there” (Thomas 29.)

That sentiment began to change as official reports started to arrive from the East India Company and from colonial officials in Boston later that month and the implications of the event started to become more apparent.

On January 21, 1774, the chairmen of the East India Trading Company sent a detailed report of the Boston Tea Party and Lord Dartmouth began interviewing eyewitnesses to the event who had arrived on the ship Hayley.

On January 27, 1774, Governor Hutchinson’s official report arrived, as well as a report from Admiral Montagu naming John Hancock and Samuel Adams as ringleaders of the event, and on January 28, Lord Dartmouth received a report from Colonel Leslie predicting the need for more soldiers in order to maintain control in Boston.

News reports about the event originally published in the Boston Gazette were reprinted in the London newspapers, making the British public aware of the incident for the first time.

In response, colonial representative Benjamin Franklin was summoned by solicitor-general Lord Wedderburn to appear before the British Privy Council on January 29, 1774.

At the meeting, Wedderburn verbally attacked Franklin in front of the council and a group of spectators for nearly an hour and accused him of leaking letters written by colonial Governor Thomas Hutchinson which the council believed contributed to the civil unrest that caused the Boston Tea Party.

The letters in question were official documents advising England on how to deal with the growing rebellion in Boston and the rest of the colonies.

Franklin had shared the letters with some colleagues in Boston who published them. As a result, the letters outraged the colonists and are believed to have contributed to the hostility that resulted in the Boston Tea Party.

After watching the attack on Franklin, the cabinet held a meeting and decided to take “effectual steps…to secure the dependence of colonies on the Mother Country.”

Although the British government had previously made compromises by repealing many of the Townshend Acts, the Boston Tea Party forced the British to take a stronger stance on its policies.

At a meeting on February 4, the Cabinet of the United Kingdom, the senior decision-making body of the British government, made a few suggestions for possible punishments.

First, the Cabinet consulted Wedderburn and the attorney general, Edward Thurlow, about the possibility of prosecuting any of the participants for treason.

The Cabinet decided against this since witnesses couldn’t or wouldn’t name names which meant there was no hard evidence to secure a conviction of any specific participant.

They also considered bringing the participants to trial or banning them from holding public office but the lack of hard evidence against any specific person made this implausible.

The Cabinet even went so far as to approve an arrest warrant for John Hancock, Thomas Cushing, Joseph Warren and Samuel Adams but as they tried to gather more evidence it became obvious to them that there wasn’t enough to secure a treason charge against them.

Since the British public was demanding a response to the Boston Tea Party, the Cabinet instead decided to punish the entire town of Boston and make an example out of it for the other colonies.

As Lord Chancellor Aspley explained, it was desirable “to mark out Boston, & separate that town from the rest of [the] delinquents.”

As a result, the British officially reacted to the Boston Tea Party with a series of acts, known as the Coercive Acts, which aimed to suppress the rebellion in Massachusetts.

On February 19, 1774, the Cabinet began drafting what would become the Boston Port Act in Parliament. This bill would order the closing of the port of Boston until the town had repaid the East India Company for the tea.

Lord North admitted that the bill would punish an entire town, not just the people responsible for the tea party, but he argued that Boston “had been the ringleader of all violence and opposition to the execution of the laws of this country. New York and Philadelphia grew unruly on receiving the news of the triumph of the people of Boston. Boston has not only therefore to answer for its own violence but for having incited other places to tumults.” (“Proceedings and Debates” 75.)

Parliament passed the bill on March 25, 1774 and it went into effect on June 1 of that year.

Next came the Massachusetts Government Act. Passed on May 20, 1774, this bill restricted town meetings and made it so positions on the Governor’s council were appointed by the British government. This essentially took the council and the governorship out of the control of the colonists.

The third act was the Administration of Justice Act. Passed on May 20, 1774, this bill made British officials immune to criminal prosecution in Massachusetts. To the colonists, this meant that soldiers would be allowed to perpetrate more crimes like the Boston Massacre without fear of prosecution.

This was followed by the Quartering Act, which required colonists to house British soldiers in their homes if needed. The colonists disliked this law because they were suspicious of any law that made it easier for troops to be in close quarters with them.

In mid-April, while these new laws were still being discussed, some members of Parliament worried that these new laws were too harsh and would create an even stronger backlash against British officials in the colonies.

Hoping to avoid this they asked the ministry, which is the upper house of Parliament, to counterbalance these new laws with a conciliatory measure and suggested repealing the tea duty to soften the impact of the new laws.

On April 19, Edmund Burke gave a now famous speech on the floor of the House of Commons during which he asked Parliament to “reflect how you are to govern a people who think they ought to be free, and think they are not. Your scheme yields no revenue; it yields nothing but discontent, disorder, disobedience” (Burke 527.)

Lord North responded by declaring that repealing the tea act would not stop the resistance and would only reward Boston for its unlawful behavior. As a result, Parliament rejected the motion 182 votes to 49.

On May 2, 1774, pro-American member of Parliament, Isaac Barre, responded somberly to the vote by declaring “We had been the aggressors from the beginning and like all other aggressors we shall never forgive them the injuries we have done them” (Thomas 81.)

News of the Boston Port Act reached Boston in early May of 1774 and the colonists responded with, not surprisingly, political resistance.

The colonists held a town meeting on May 13, during which they called upon the other colonies to join in the rebellion and stop all trade with Great Britain until the Boston Port Act was repealed.

Although the Coercive Acts were intended to isolate Boston from the rest of the colonies, it instead caused the rest of Massachusetts and the other colonies to rise up in protest.

Instead of making an example out of Boston, the British made a martyr. Towns throughout New England sent aid and supplies to Boston, colonists throughout Massachusetts forced the royally appointed councilors to resign, and tea protests were held throughout the colonies during which British tea was burned in public demonstrations.

The colonial resistance continued throughout the year, which infuriated the king. In November of 1774, King George III wrote to Lord North declaring “The New England Governments are in a state of rebellion. Blows must be decided whether they are to be subject to this country, or independent.”

On January 27, 1775, Lord Dartmouth sent a letter of instruction to General Gage directing him to arrest and imprison the principal members of the newly established Provincial Congress and authorized him to use force if necessary to suppress the rebellion.

On April 19, 1775, Gage did just that when he sent troops to Concord to seize and destroy the colonist’s ammunition stockpiles there. This prompted the militia to turn out and exchange fire with the British soldiers in Lexington and Concord.

Under heavy fire, the British soldiers retreated back to Boston and the militia surrounded the city, trapping them inside which kick started the Siege of Boston and the first phase of the Revolutionary War.

Sources:

Great Britain Parliament. Proceedings and Debates of the British Parliaments Respecting North America, 1754-1783 Volume 4. Kraus International Publications, 1982.

Burke, Edmund. The Speeches of the Right Hon. Edmund Burke. Columbia University, 1847.

Thomas, Peter D.G. Tea Party To Independence: The Third Phase of the American Revolution 1773 – 1776. Oxford University Press, 1991.

Carp, Benjamin L. Defiance of the Patriots: The Boston Tea Party and the Making of America. Yale University Press, 2010.

“George III’s official correspondence July 1772-1783.” Royal Collection Trust, rct.uk/collection/georgian-papers-programme/george-iiis-official-correspondence-july-1772-1783

Adams, John. “1773. Decr. 17th.” National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/01-02-02-0003-0008-0001