Among the many historic towns in Massachusetts are a handful of ghost towns. These towns were abandoned either decades or centuries ago for a variety of reasons.

Some of these ghost towns are still open to visitors today while others are off limits or completely inaccessible to the public.

The following is a list of ghost towns in Massachusetts:

Catamount:

Catamount is a former village located on a mountain in Colrain, Massachusetts.

While Colrain was settled in 1735, Catamount wasn’t settled until sometime in the mid 1700s or early 1800s and was mainly a farming community.

In 1812, Catamount became known for being the first town to fly the United States flag over its school house.

Catamount was eventually abandoned in the early 20th century and in 1967 it was purchased by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. A large portion of the town is now a part of Catamount State Forest.

The schoolhouse and most of the buildings are now gone and the village’s roads have deteriorated so badly they were closed to vehicular traffic about a decade ago but visitors can still explore the area on foot.

Dana:

Dana was a town in the Swift River Valley that was lost in 1928 when the town was submerged due to the Quabbin Reservoir project.

Dana was settled in 1676 as a part of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and was officially incorporated on February 18, 1801. It was disincorporated on April 28, 1938 as part of the Quabbin Reservoir project and flooded shortly after.

Due to Dana being at a higher elevation than the other towns flooded in the Quabbin Reservoir project, much of Dana has remained unsubmerged.

What remains includes old foundations from the town’s schoolhouse, town hall, hotel and homes, an empty field where the town cemetery once was and the old town common, which is marked by memorials to the town’s historic buildings.

The old road to the town is closed to vehicles but pedestrians can still hike into the town on Old Dana Road and visit it.

Davis:

Davis is an abandoned mining village in the town of Rowe, Massachusetts. The village was the site of the Davis Pyrite Mine which was once the largest pyrite-mine in the state.

The Davis Mine was established around 1882 by New York City entrepreneur Herbert Jerome Davis after an iron pyrite outcrop was discovered in Rowe by geology students from Amherst College. Davis viewed the samples discovered by the Amherst students, visited the town and purchased the local C.C. Brown farm and parts of neighboring properties, which contained a large section of ore, and then launched the Davis Sulphur Ore Company.

The mine went into production in January of 1883 and began producing 20 tons of ore a day. By 1890, 10 buildings had been constructed around the mine for ore-processing, boilers, machinery, blacksmithing and housing for workers. A tramway was also built to haul away mining waste, a U.S. Post Office and company store were eventually established and the Davis Mining School was constructed in the 1890s.

Davis died unexpectedly in 1905 and the mine became run down over the next few years due to weak leadership and poor maintenance. A series of cave-ins occurred throughout the mine and then a major cave-in occurred in July of 1909, which shut down most of the mining operations. Near surface mining occurred until 1911 but it was not profitable enough to keep the mine going and it closed in 1912. The Davis Sulphur Ore Company eventually sold the property to John Davenport.

The Davis Mining School continued for another 12 years until it was shut down in 1924. The school was abandoned and was still standing by the 1970s but had badly deteriorated.

The mine is now located on private property on Davis Mine Road. All that remains are four capped mine shafts, some sulphur ore, several foundations of old buildings and some old machinery.

Dogtown:

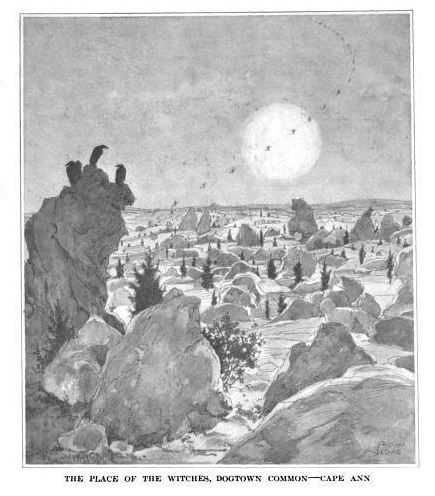

Dogtown is an abandoned village in the city of Gloucester, Massachusetts.

The village was originally known as the Commons or the Common Settlement and was first settled sometime between 1646 and 1650 by colonists who wanted to avoid the pirate and Native-American attacks that plagued the harbor and coastline of Gloucester. At its peak, the village was home to around 60 to 80 families.

After the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812 ended, the threat of pirates and British bombardment disappeared and the residents of Dogtown slowly began to leave the village and relocate to the harbor and coastline.

The empty village quickly began to attract outcasts and drifters who squatted in the abandoned homes. It was around this time that the village acquired the name “Dogtown” either because of the packs of stray dogs that wandered the town or because of the undesirable inhabitants that the village attracted.

Many of the outcasts who lived there were women who were suspected to be witches. Stories often circulated of the spells these women cast on the various merchants and laborers who passed through Dogtown.

By 1839, the squatters and inhabitants of Dogtown had eventually died, moved away or were removed.

The village’s last resident, Cornelious Finson, was dragged out of one of the cellar holes in February of 1839 and placed in the poor house in Gloucester, where he died seven days later.

The last remaining house in Dogtown was demolished in 1845 and all that remains now are cellar holes where the residents houses once stood.

The village was used as pastureland afterwards and was occasionally visited by hikers such as Henry David Thoreau who stopped by the village in 1858 during a walking tour of Cape Ann.

In 1927, local entrepreneur Roger Babson purchased 1,150 acres of Dogtown and began documenting its historic sites, marking the cellar holes with numbers to indicate who lived there and also began inscribing the boulders that covered the area with inspiring messages.

In 1935, Babson donated Dogtown to the city of Gloucester and it was turned into a public park.

Enfield:

Enfield was a town in the Swift River Valley that was lost in 1928 when the town was submerged due to the Quabbin Reservoir project.

The town was originally settled by Robert Field, whom it is named after, as the south parish of the town of Greenwich and was fully incorporated as its own town on February 15, 1816.

By 1850, the population of Enfield was 1,100 people, making it one of the largest of the Quabbin towns. It was a primarily a farming community but also had a number of textile mills and factories.

On April 28, 1938, Enfield was disincorporated as part of the Quabbin Reservoir project and on August 14, 1939, the reservoir began to fill.

The areas of Enfield that remained above water were annexed to Belchertown, New Salem, Pelham, and Ware.

Greenwich:

Greenwich was a town in the Swift River Valley that was lost in 1928 when the town was submerged due to the Quabbin Reservoir project.

The land that the town sits on was granted in 1737 to descendants of the veterans of King Philip’s War and was known as Quabbin. In 1754, the town was officially incorporated as Greenwich.

The town was primarily a farming community but also had a number of textile mills and factories.

On April 28, 1938, Greenwich was disincorporated as part of the Quabbin Reservoir project and was flooded shortly after. Since the town was at a lower elevation than the surrounding towns, it is largely submerged except for the hilltops of Curtis Hill, Mount Lizzie and Mount Pomeroy, which are now islands within the reservoir.

Haywardvill:

Haywardvill was a mill village established by Nathaniel Hayward in the mid 1800s. The village was established in 1858 when Hayward bought a shoe factory near Spot Pond Brook in Stoneham from Elisha Converse.

The single factory quickly grew to become an industrial village where Hayward and Charles Goodyear later invented vulcanized rubber. At its peak, four mills were operating in the town,

As technology advanced and water-powered mills became more and more obsolete the mills in Haywardvill had to close down altogether when Medford, Malden and Melrose took away Haywardvill’s water rights sometime around 1870.

The remaining buildings were relocated to Ravine Terrace and Brook Street in Stoneham.

In 1894, the land was purchased by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts for use as a park and later became the Middlesex Fells Reservation.

All that remains of the village now is the old foundation to the rubber factory and some stone walls. The site is accessible by trail and trail maps are available at the visitor center at the John Bottume House.

Long Point:

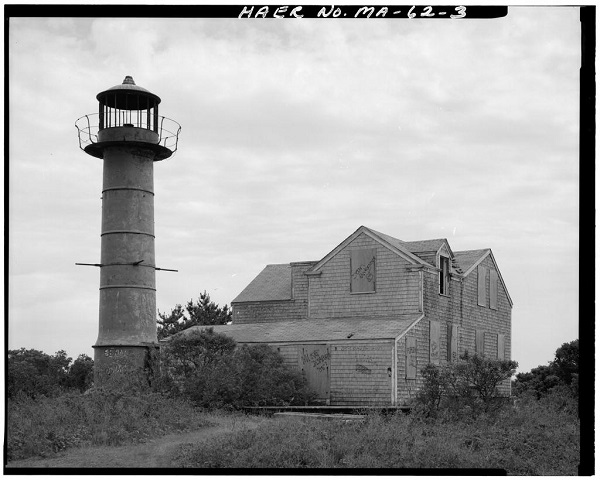

Long Point is an abandoned fishing village that was settled near Provincetown, Cape Cod in 1818.

In 1827, the Long Point lighthouse was erected to help guide ships into Provincetown harbor. The town quickly grew over the decades as more and more fishermen settled in Long Point. By 1846, a school house was built to educate the local children.

Other buildings were eventually constructed as well, including a general store, post office, bakery, salt works, a wharf and a total of six windmills. At its peak in the 1840s, the population totaled around 200 people.

The village began to decline in the 1850s when the salt works became less profitable due to cheaper salt deposits being discovered in New York and the fish population began to dwindle due to over fishing. The villagers began to pack up and leave for Provincetown in droves, many of them taking their houses and town buildings with them, which they dismantled and floated across the harbor on scows.

By 1861, only two houses and the lighthouse remained in Long Point. During the Civil War, earthen mounds were constructed on Long Point to serve as a Civil War battery and barracks were constructed for soldiers to sleep in. One of the remaining two houses was used as officer’s headquarters. When the Civil War ended, Long Point was abandoned again.

In 1875, Long Point’s wharf was repurposed to process whale carcasses for the Cape Cod Oil Works. By the early 20th century whaling became obsolete and now all that remains of the wharf are some pilings and the remains of a brig hull.

During WWII, a wooden cross was placed at the top of one of the Civil War batteries in honor of a local Provincetown man, Charles Darby, who had died in the war. The lighthouse and the wooden cross are the only things still standing in Long Point.

Norton Furnace:

Norton Furnace, also known as Norton Mills and Copperworks Village, was a town established near Norton, Mass in 1825. The settlement was established by Annes A. Lincoln Jr when he constructed a furnace for manufacturing iron on the north side of a local brook there.

By 1837, the furnace produced 375 tons of iron and employed 25 men. It continued to grow each year and by 1850 the village had 25 houses and a store. By 1855, the furnace produced 500 tons of iron and employed 30 men.

In the 1860s, a branch of the Old Colony Railroad ran through the village and by 1871 a train depot was constructed in the village.

Two companies operated in the village, the North Copperworks and the Norton Furnace, until the 1890s when the companies relocated to Boston and Worcester.

It is not exactly clear what became of Norton Furnace but it mostly likely became abandoned after the copperworks and the furnace moved out of the area. The area where Norton Furnace was located is now called Meadowbrook.

Prescott:

Prescott was a town in the Swift River Valley that was lost in 1928 when the town was submerged due to the Quabbin Reservoir project.

The town was incorporated in 1822 from parts of Pelham and New Salem and was partially built on Equivalent Lands, which was land that the Province of Massachusetts Bay made available to settlers of the Connecticut Colony.

At its peak in 1900, Prescott had only about 300 residents.

The town was home to a number of historic sites related to Shay’s Rebellion, such as the former site of Daniel Shay’s home and the Conkey Tavern where the rebellion was planned.

On April 28, 1938, Prescott was disincorporated as part of the Quabbin Reservoir project and was flooded shortly after. The majority of the town is still above water and is known as the Prescott Peninsula, which is a wildlife sanctuary that is closed to the public.

Questing:

Questing was the site of a historic military fort and a settlement in New Marlborough.

The fort was established in the early 18th century on what later became Leffington Hill and was where the first non-Native American children, the Brookins twins, were born in the town.

In the mid 1800s, two brothers, William and Jerome Leffingwell, settled the area when they established a farm on Leffington Hill. The brothers both died in farming accidents and the remaining family members moved to the midwest.

The Leffingwell farmstead changed owners many times before it was eventually abandoned in the early 1900s.

In the 1970s, noted pharmacologist Dr. Robert Lehman purchased the old farmstead and named it Questing after a mythical beast called the Questing in the King Arthur legend.

In 1996, Lehman donated the old farmstead to the Trustees of Reservations who helped turn it into a 438-acre nature reserve called Questing Reservation. The only thing that remains of the old homestead on the reservation today are the cellar holes of the farmhouse, the ruins of the barn and some stone walls.

The Questing Reservation is open to the public and features walking trails, hardwood forests, wetlands and 17-acre field of native wildflowers as well as the ruins of the old farmstead.

Whitewash Village:

Whitewash Village was a settlement, sometimes called Monomomy Village, located on Monomoy Island on Cape Cod sometime in 1711.

The settlement was named after either the local whitewashed rocks or the village’s whitewashed buildings, it’s not exactly clear.

The settlement began in 1711 when a tavern and inn, known as Stewart’s Tavern, was established at Wrecks Cove for local sailors who were either shipwrecked or taking refuge in the cove.

By 1835, a small community had sprouted up along the harbor, known as Powder Hole harbor, and it quickly grew to about 200 people, mostly fishermen who fished the local waters and sold their catch to markets in New York and Boston.

Two wharves were built complete with supply stores and storage sheds. About a dozen houses were also constructed, mostly simple shacks, as well as a tavern and inn called Monomoit House and a schoolhouse.

The village slowly began to decline in 1860, after a powerful winter storm hit the island and dramatically changed the coastline. The northwest point of the island was swept away, bringing sand into Powder Hole harbor which made it too shallow for ships to use. The dramatic landscape change also drove away the large number of fish that the villagers relied on to make a living.

As the fishing business gradually declined, more and more villagers moved to the mainland, some of them even taking their houses with them by dismantling them and floating them on rafts, until the village was completely abandoned.

In 1864, former schoolmaster of Whitewash Village, Giddings Ballou, wrote an article about the village for Harper’s Monthly Magazine in which he described it as a small fishing village that served as a place of refuge for “exhausted and frost-bitten mariners.”

Ballou said the village often flooded at high tide prompting the locals to visit the local tavern in boats and forcing the children to wade through the water to get to school.

Ballou eulogized the village in his 1864 article, stating:

“But the goldenage of Monomoy has passed away. And the sand is sweeping about the entrance to the little harbor, and its habitants, mindful of the encroaching wave, have begun to forsake the beach for the main, taking with them evenroof-tree and hearth-stone. And the ‘Captain’ no more shells the native clam for the big pot upon the stove, … the good landlady is dead. And there is a shadow of sadness on the glory of Monomoy.”

The island was taken over by the U.S. government during WWII and became the Monomoy Island Gunnery Range in 1944. The gunnery was abandoned in 1951.

In 1970, Monomoy Island was purchased by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and was designated a national wildlife refuge. All that remains of the village now is the Monomoy Lighthouse.

Sources:

Yelle, Joseph. The Devil’s Footprints and Other Sketches of Old Norton. Norton Historical Commission, 1979.

Grey, Spencer. “The Village at Monomoy Point.” Chatham Historical Society, chathamhistoricalsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/AtAtwood_ccc_4-3-14.pdf

“Questing History.” The Trustees, thetrustees.org/content/questing-history/

“Questing.” The Trustees, thetrustees.org/place/questing/

MHC Reconnaissance Survey Town Report Norton, 1981, sec.state.ma.us/mhc/mhcpdf/townreports/SE-Mass/nrt.pdf

“Hidden Cape Cod: A Village That Used to Exist in Provincetown.” Cape Cod, 21 Jan. 2021, capecod.com/lifestyle/hidden-cape-cod-a-village-that-used-to-exist-in-provincetown/

Rathsmill, Victoria. “Middlesex Fells: Haywardvill Returns from the Past.” Wicked Local Malden, 23 April 2014, malden.wickedlocal.com/article/20140423/News/140429134

“Quabbin Islands.” Downstream, Massachusetts Department of Conservation, No. 30, Fall 2013, mass.gov/files/documents/2017/09/29/fall%202013.pdf

“Background of Enfield, Mass.” University of Massachusetts Amherst, findingaids.library.umass.edu/ead/mums010

“Dogtown (Dogtown Common or Dogtown Village.” Essex National Heritage Area, essexheritage.org/attractions/dogtown-dogtown-common-or-dogtown-village

Earls, Eamon McCarthy. An Industrial History of Rowe, Massachusetts. Academia, academia.edu/12037655/Industrial_History_of_Rowe_Massachusetts

McCarthy, Helen. The Story of the Davis Mine, Rowe, Massachusetts. Rowe Historical Society, 1967.

Bourgault, Bethaney. “The Lost Towns of the Quabbin Reservoir.” New England Today, 2 Nov. 2020, newengland.com/today/living/new-england-history/lost-towns-quabbin-reservoir/

“About Colrain.” Town of Colrain, colrain-ma.gov/p/16/About-Colrain

“Catamount State Forest.” Franklin Sites, franklinsites.com/catamount/