In 1684, the Massachusetts Bay Colony charter was revoked due to repeated violations of the charter’s terms.

These violations were:

- The colonists continued to trade with other countries despite the Navigation Acts prohibiting them from doing so

- The colony ran an illegal mint that made coins without the king’s image on them and melted down English coins to remake them into their own coins

- The Massachusetts General Court created a number of laws that did not align with England’s laws, particularly religious based laws

The illegal mint first came to the attention of King Charles II in 1662, when Sir Thomas Temple, proprietor and governor of Nova Scotia, met with Charles II and his Privy Council.

During the conversation, Temple took some coins out of his pocket and presented them to the king, one of which was a Boston coin, also known as a Pine tree shilling or Bay shilling.

The coin did not have an image of the king on it and instead was stamped with the date 1652 on the front and had an image of a pine tree on the back.

Upon seeing the coin, Charles displayed “great warmth against that colony; among other things he said, they had invaded his prerogative by coining money” (Barth 501.)

When the king asked what tree was pictured on the back, Temple tried to appease him by fabricating a story that it was a “royal oak” which was the type of tree used to build the ship that brought Charles II across the English channel into exile following the defeat by Cromwell at the Battle of Worcester in 1651.

Temple stated that the colonists didn’t dare put his name on their coins during his exile so they instead stamped the image of the tree that saved his life. This was a complete lie though because the colonists overwhelming supported Parliament, not the king, during the English Civil War.

The lie seemed to work, at least temporarily, because Charles laughed in response and called the colonists a “parcel of honest dogs” (Barth 502.)

The king could only be appeased for so long though and in 1665, Charles II sent a royal commission to New England, accompanied by nearly 400 troops, to look for violations of the Navigation Acts.

The other New England colonies willingly complied with the commission but when the commission arrived in Boston, the Massachusetts General Court declared the commission illegal and refused to cooperate with them.

The commission continued anyway and ordered that the mint house stop making coins. The Massachusetts General Court rejected the commission’s injunction, declaring in a petition to the king that it was contrary to “the liberties of Englishmen, so we can see no reason to submit thereto” (Barth 503.)

In response, the king ordered the General Court to send representatives to London immediately, which the General Court declined and instead sent the Royal Navy a gift of two large ship masts.

The king and his Privy Council decided not to pursue the matter and all official communication between the colony and the crown ceased from 1666 to 1674.

The reason for the lack of communication was due to the fact that England had more pressing matters to deal with at the time, such as the Great Plague of London that began in 1665, the Great London fire of 1666, warfare with Holland and a third Anglo-Dutch war in 1672.

An illegal mint run by an unruly colony was the least of England’s concerns at the time, according to an article by Jonathan Edward Barth in the New England Quarterly:

“The controversy over the mint paled in comparison. Edicts from the Crown, in this early period of the Restoration, generally required a certain degree of voluntary compliance from the entity being commanded, for the king lacked sufficient wherewithal to enforce his will in all cases. So rather than expanding valuable time, money, and resources, the Crown grudgingly tolerated a headstrong, politically jealous Massachusetts government. As colonial administrator Mathias conceded in 1666, the task remained ‘to find a way to bring down the pride of Massachusetts’” (Barth 505.)

It wasn’t until 1675 that the king was finally ready to address the problem with Massachusetts after the proprietors of the Maine and New Hampshire colonies, Robert Mason and Ferdinando Gorges, made repeated claims to the land that Massachusetts occupied based on the fact that they had previously received a patent for that land in 1622.

Charles II saw the land dispute as an opportunity to reign in the unruly Massachusetts Bay Colony. That year, he established the Council of Trade and Plantations, or Lords of Trade, a committee of nine men within the Privy Council tasked with keeping an eye on colonial affairs.

In 1676, the Lords of Trade appointed a courtier named Edward Randolph to deliver a royal letter to Massachusetts requesting them to send agents to London immediately to discuss Mason and Gorges claims.

The letter read:

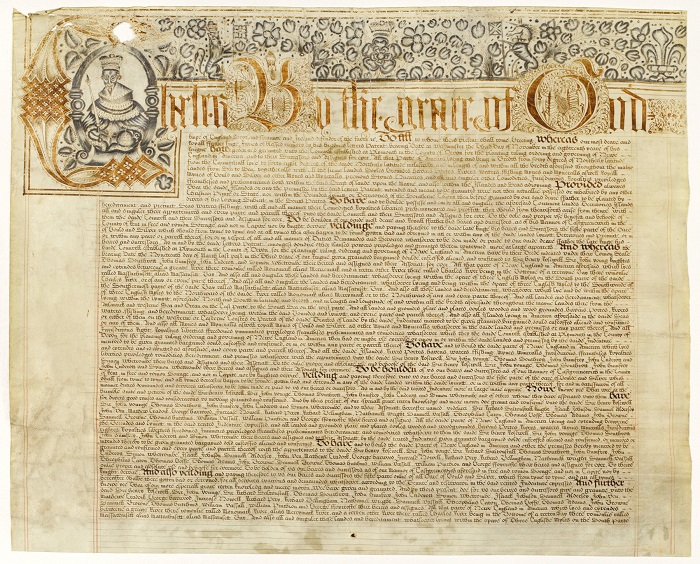

“Trusty and well beloved we greet you well. We have been, for a long time, solicited by the complaints of our trusty and well beloved subjects Robert Mason and Ferdinando Gorges, to interpose our royal authority for their relief, in the matter of their claims, and the right pretended by them to the two provinces of New Hampshire and Mayne in our territory of New England. Out of the possession whereof they are kept, as they alleage, by the violence and strong hands of our subjects, the people of Boston, and others of the Massachusetts colony. The said petitioners have presented to us a very long deduction of all proceedings from the beginning; as well in proof of their demands, as of the hardships they have undergone. And upon the debate of these matters before us in council, we think it is high time to afford a solemn hearing to the complaints of our subjects, and to see that justice be equally administered unto all. But forasmuch as no man hath appeared before us to make answer in behalf of the said people our subjects, who are now under your command and that is not agreeable to our royal justice, to conclude anything on the hearing of one side, without the other be called. We have therefore directed that copies of the two petitions presented to us be transmitted herewith unto you, that you may see and know the matters they contain, and show cause why we should not afford the petitioners that relief which is prayed for by them. Therefore we do, by the advice of our said council, hereby command that you send over agents, to appear before us, in six months after your receipt of these our letters, who, being fully instructed, and sufficiently impowered to answer for you, may receive our royal determination in this matter depending for judgement before us. And to the end these our gracious intentions for doing equal justice to all parties may be the better effected without any delay or frustration. We have thought fit and do hereby require and command that this our letter together with the aforementioned petitions herewith transmitted to you be read in public and full council, and that Ed. Randolph by whom we send our said letter with the petitions be admitted into the council to hear the same read there, he being by us appointed to bring us back your answer, or render us an account of your proceedings in this matter. And so we bid you farewell. Given at our court at Whitehall to the 10th day of March 1676 in ye 28th year of our reign. By his command, H. Coventry” (Randolph 193-94.)

After arriving with the letter in Boston in June of 1676, the Massachusetts General Court initially dismissed Randolph but soon after sent two agents, William Stoughton and Peter Bulkley, to London as requested.

Randolph then embarked on a fact-gathering mission across the colony, finding many merchants eager to inform him of the colony’s violations of the charter.

Randolph returned to London in September of 1676 and wrote a lengthy report to the Lords of Trade detailing what he discovered, during which he answered the 12 areas of inquiry the committee had requested him to investigate, which were:

- Where are the legislative and executive powers of the government seated?

- What laws exists that are contradictory to English laws?

- How many church members, freemen, inhabitants, planters, servants, slaves are there and how many can bear arms?

- How many soldiers and experienced officers are there and are they trained militias or standing forces?

- What castles and forts are there in New England?

- What are the boundaries and contents of the land?

- What communication do they have with the French and the [Dutch] government of New York colony?

- What has been the present cause of the war with the natives [King Philip’s War]?

- What products do they produce, what products do they import, how many ships do they trade with yearly, where are the ships built, which countries do they trade with and do they abide by the Navigation Acts?

- What are the taxes, fines and duties on goods exported and imported into the colony, how much money does it generate for the government and how is it collected?

- How do they feel about the government of England and what colonial magistrates are the most popular and are most likely to be elected/re-elected?

- What is the present state of the ecclesiastical government, how are the universities filled and by whom are they managed?

In regards to the question about colonial laws that contradicted English laws, which was one of the terms of the Massachusetts Bay Colony charter, Randolph stated there were 10 laws in the colony that violated English laws, which were:

- People aged 21 years of age who have been excommunicated or condemned were allowed to make wills and dispose of estates and lands.

- In capital cases, dismembering and banishment, if there was no applicable law on the books the offender may be tried by the word of God and judged by the General Court.

- Ministers are ordained by the people

- Colonists caught celebrating Christmas were fined and colonists who fail to attend church were also fined.

- Colonists were not obligated to serve in any wars except those “enterprized by that commonwealth, by the content of a general court, or by authority derived from them.”

- No one shall be married by anyone but a magistrate

- Any “true” Christians fleeing tyranny and oppression could find refuge in the colony

- Squatters who occupy land for five years can take possession of the land even if it belongs to someone else.

- No oaths were required to be taken except those allowed by the General Court.

- Oaths of allegiance and supremacy were not required to be taken by the magistrates nor the colonist, only an oath of fidelity to the government

On May 6, 1677, Randolph wrote a brief report to the Committee of Foreign Affairs entitled “Representation of ye Affaires of New England” also known as “The Present State of the Affaires of New England.” The report listed eight accusations against the Massachusetts Bay Colony, which were:

- They were usurpers without a royal charter

- They did not take an oath of allegiance to the King

- They protected Goffe and Whaley, who were wanted for the murder of Charles I

- “They Coyne money with their owne Impress.”

- They had murdered some English Quakers because of their religious beliefs

- They opposed the King’s commissioners in the settlement of New Hampshire and Maine

- They imposed an oath of fidelity to Massachusetts Bay on all inhabitants

- They violated the acts of trade and navigation robbing the King of his custom duties

The document was then forward to the Lords of Trade for discussion at their June 7th meeting which later led to an investigation into the charges.

In July of 1677, the Lords of Trade launched a formal investigation into Randolph’s charges. At a July 19th hearing on Randolph’s charges, Stoughton and Bulkley testified and answered various questions about the claims, particularly on the illegal mint.

When questioned about the mint and asked whether “treason be not herein committed” and, if so, whether it was enough to revoke the charter, Stoughton and Bulkley replied that the mint was only established for economic reasons, not political ones, and then falsely claimed that they had since discontinued it (Barth 509.)

Stoughton and Bulkley then apologized on behalf of the colony for any offense and promised that oaths of allegiance and supremacy would be taken by colonial officials from now on.

After the hearing, the Lords of Trade discussed the matter for several days and ultimately decided that if the General Court were to simply apologize to the king for the illegal mint, he might allow them to continue to mint under his authority, thus allowing the colony to keep the mint for economic reasons while also negating its political implications.

In addition, the colony would also required to obey the Navigation Acts. If these instructions were followed, the Lords of Trade promised that “His Majestie will not destroy their charter, but rather by a supplemental one to be given them, set all things right that are amiss” (Barth 509.)

Stoughton and Bulkley were relieved and proceeded to “humbly implore his Majestie’s gratious pardon” for the mint and expressed their gratitude that the mint would continue under whatever “impress he pleases” (Barth 509.)

Upon hearing of the news, the Massachusetts General Court was not as pleased. They refused to apologize for the mint and balked at the idea of impressing coins with the king’s image, stating “we shall take it as his Majestie’s signal owning of us” which they considered a threat to their independence, according to Barth:

“Independence was a precious commodity, and it was not to be relinquished in fact or in form. The Bay shilling would not announce that the colonists were ‘owned’ by their king. The mint controversy was a battle over symbols, one waged not only between England and Massachusetts but also within the Bay Colony. The Lords of Trade recognized that for royal authority to assert itself properly in Massachusetts, the mints must be reclaimed for the Crown” (Barth 511.)

Not only did the General Court refused to apologize or change the coin impress but it also refused to administer oaths of allegiance to the king. It partially relented on the issue of trade but only after passing its own laws that were quite similar to the Navigation Acts, thus still managing to assert its own legislative authority.

The following year, Randolph informed the Lords of Trade that the General Court had not been administering oaths of allegiance nor had they stopped pressing coins with their own impress and he declared that by passing a law similar to the Navigation Acts, the General Court encouraged the colonists “to believe that no Acts of Parliament…are in force with them” (Barth 511-512.)

As a result, in September of 1679, Edward Randolph was sent to the colony to act as collector, surveyor and searcher of the customs for all New England, making him the first imperial officer to serve full-time in the colony. Meanwhile, the colony continued pressing its coins without an apology nor an imprint of the king.

On December 25, 1679, Stoughton and Bulkley arrived back in Boston. In February, the General Court thanked them for their long service abroad and awarded them both 150 pounds as a show of appreciation.

On September 30, 1680, King Charles II sent a letter to the Governor and Council of Massachusetts Bay requiring them to give allegiance to the king and obey his commands. Included in the letter was a copy of Randloph’s report from May 6, 1677 accusing the colony of eight violations of its charter.

On April 6, 1681, Randolph petitioned the king, informing him the colony was still pressing their own coins which he saw as high treason and believed it was enough to void the charter. He asked that a writ of Quo warranto (a legal action requiring the defendant to show what authority they have for exercising some right, power, or franchise they claim to hold) be issued against Massachusetts for the violations.

On October 21, 1681, the General Court received a letter from the king listing several complaints against the colony, one of which was the mint, and also requested that two new agents be sent to London to replace Stoughton and Bulkley.

In addition, the letter also stated that a writ of Quo warranto would be issued during the next term in the spring. Some sources indicate the writ was issued but was never served for technical reasons.

On February 15, 1682, during a special session of the General Court the letter from the king was read and the court decided to expedite the process of selecting new agents to send to London. In March, John Richards and Joseph Dudley were selected.

On August 20, 1682, Richards and Dudley arrived in London but without the authority from the General Court to revise the charter.

In March of 1683, after the Lords of Trade requested the General Court to give Richards and Dudley the authority to revise the charter, the General Court sent a letter to the agents refusing to do so and ordered them not to answer any questions if a writ of Quo warranto was issued.

On April 2, 1683, Randolph departed Boston for London.

On June 4, 1683, Randolph submitted a petition to the Lords of Trade which accused the colony of committing 17 acts of high misdemeanor, with the mint being the first among them.

After a series of back and forth exchanges with the General Court and the Massachusetts agents, the Lords of Trade issued a writ of Quo warranto against the charter on June 27, 1683. The writ was officially signed by the king’s council on July 20.

In October of 1683, Randolph arrived in Massachusetts and delivered the writ along with a letter from King Charles II which stipulated that the charter might survive if the Crown were invited to regulate and revise its specific articles.

The proposition sparked a heated debate in the General Court, with the more moderate members stating it was reckless to keep defying the Crown. Nevertheless, in December of 1683, the lower house of the General Court voted to reject the king’s proposal.

On April 16, 1684, a writ of Scire facias (a legal action requiring the defendant to appear in court and show cause as to why a judicial record should not be enforced) was issued against the Massachusetts Bay Company by the Chancery court but was incorrectly addressed to the wrong sheriff in Massachusetts. Representatives of the colony did not appear at the appointed time.

On May 13, 1684, London Attorney General Robert Sawyer ruled that the previously issued Quo warranto was issued to the wrong sheriff and delivered only after the period for responding to the summons was passed and suggested dropping the matter and focusing instead on the writ of Scire facias.

On June 2, 1684, another writ of Scire facias was issued, and was again addressed to the wrong sheriff, and it ordered that the colony respond to the writ within six weeks, even though it took longer than six weeks for the writ to reach them.

On June 12, 1684, representatives for the colony appeared in court but refused to enter a plea and asked for time to send for a letter of attorney from New England to appear and plea to the charges.

On June 18, 1684, a judgment was entered against Massachusetts but it was set aside until representatives from Massachusetts could appear in court and enter a plea so a trial could take place.

In either September or October of 1684, the Massachusetts agents appeared in the Court of Chancery and explained that the colony was not given enough time to respond to the Scire facias, to which the Lord Keeper of the Great Seal of England (the officer of the English Crown charged with physical custody of the Great Seal of England) replied that no time ought to be given at all since corporations should have attorneys in court at all times to represent them (Hutchinson 340.)

Since the Massachusetts agents stated they could not receive a letter of attorney in time to enter a plea, on October 23, 1684, the Crown revoked the Massachusetts Bay Colony charter.

Sources:

Hutchinson, Thomas. The History of the Colony of Massachusetts Bay. London: M. Richardson, 1765.

Randolph, Edward. Edward Randolph: Including His Letters and Official Papers from New England, 1676 – 1703. Vol II, Prince Society, 1898.

Hart, Albert Bushnell, ed. Commonwealth History of Massachusetts. The States History Company, 1927

Barth, Jonathan Edward. “‘A Peculiar Stampe of Our Owne’: The Massachusetts Mint and the Battle over Sovereignty, 1652-1691.” The New England Quarterly, vol. 87, no. 3, 2014, pp. 490–525. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/43285101

Jordan, Louis. “Chronological Listing of Documents and Events Relating to the Massachusetts Mint.” Coin and Currency Collections, University of Notre Dame, coins.nd.edu/ColCoin/ColCoinIntros/MAMintDocs.chron.html

“Pine Tree Shilling, United States, 1652.” National Museum of American History, americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_1082064

The Charters and General Laws of the Colony and Province of Massachusetts Bay. Boston, T.B. Wait and Co, 1814.

Trying to understand this.

Was the Quo warranto, and 2 different Scire facias sent to the wrong Sherriff(s)?

Yes, it appears that they kept sending these legal notifications to the wrong sheriff without realizing the mistake.