Many Native American tribes fought in the Revolutionary War. The majority of these tribes fought for the British but a few fought for the Americans.

Many of these tribes tried to remain neutral in the early phase of the war but when some of them came under attack by American militia, they decided to join the British.

Other tribes joined the British in the hopes that if the British won, they would put a stop to colonial expansion in the west, as they had done with the Royal Proclamation of 1763.

The following is a list of the various tribes who fought in the Revolutionary War:

Wabanaki Confederacy:

The Wabanaki Confederacy was an alliance of five northern tribes: the Penboscot, Maliseet, Passamaquoddy, Abenaki and Micmac.

As a whole, the tribes of the Wabanaki Confederacy were reluctant to join the war effort but some members of the various tribes did take part in a few engagements, according to Colin G. Calloway in his book The American Revolution in Indian Country:

“In Maine and Nova Scotia, Passamaquoddies, Micmacs, and Maliseets were reluctant to become involved in a war that had little to offer them. Massachusetts passed a resolution in July of 1776 that five hundred Micmac and Maliseet (Saint Johns) Indians be employed in the continental service. Maliseet chiefs Ambrose St. Aubin and Pierre Tomah sometimes spoke as if they were engaged in a common cause to protect their lands and liberties, but eastern Indians often deftly avoided the billigerent’s recruiting efforts. Delegates who attended the Treaty of Watertown in 1776 exceeded their authority in committing the tribes to the American cause. The tribes split as British power and British goods exerted increasing influence. About a hundred principal men of the Micmac, Maliseet, and Passamaquoddy tribes took an oath of allegiance to King George between September 1778 to January 1779. With chief Ornon ‘hearty in our cause,’ a company of Penobscots served in the United States and figured prominently in the action at Penobscot in 1779. A dozen Pigwackets from western Maine petitioned Massachusetts for permission to enlist.” (Calloway 36.)

The Maliseet was a tribe with a population of several hundred that lived in Maine, and the Passamaquoddy was an eastern group of Maliseet that lived in Maine and New Brunswick.

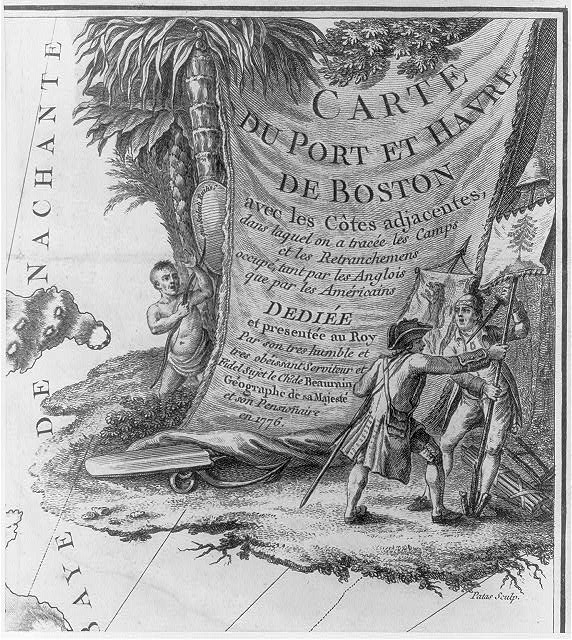

A Tory and a patriot wrestle over a liberty tree banner while a Native watches, illustration depicts British and American struggle for land ownership in North America, published in Paris circa 1776.

After the American Revolution began and hostilities broke out, the Passamaquoddy allied themselves with the Americans early in the war and the rest of the Maliseet tribe later joined them but the tribe didn’t participate in many battles, according to an article about the Passamaquoddy by Nicholas Smith on Cornell University’s website:

“It was considered a great victory for the Americans when several hundred Maliseet and a few Micmac joined the Passamaquoddy at Machias, Maine. The Indians retained their way of life, living together as was their custom, and hunting game for food. There was little actual fighting, but the Americans had the satisfaction of knowing that several hundred Maliseet would not join English forces. Their biggest contribution was as spies going to Canada and returning with news of the English plans, and attacking English coastal shipping. The Indians played a leading role in preventing an English attack on Machias by sea from being successful. The story of a young Indian lad who shot and killed the English officer of a landing barge, resulting in the English retreat, has become an important traditional tale among the Passamaquoddy.”

On July 19, 1776, the Micmac and Maliseet signed the Treaty of Watertown, which was a treaty of alliance and friendship signed between the two tribes and the United States.

On December 24, 1776, General George Washington wrote the Passamaquoddy tribe a letter asking them to send him warriors. The Penobscot tribe and the Passamaquoddy responded by providing 600 warriors.

In August of 1777, Chief Francis Joseph Neptune of the Passamaquoddy tribe reportedly fired one of the first shots of the Battle of Machias in Maine, hitting and killing a British officer standing on the deck of the British frigate Mermaid at a considerable distance.

Throughout the war, the Massachusetts government continued to provide the Passamaquoddy with supplies and ammunition in recognition of their service.

After the war ended in 1783, Neptune worked continuously to prevent white encroachment on Indian lands in Maine.

In 1796, Neptune and other tribal leaders secured a land treaty from the Massachusetts government that included a 23,000 acre reservation near Perry, Maine.

The Penobscot, a tribe with a population of a few hundred who lived in Maine, had been long-standing allies of the French during the earlier colonial wars.

The Penobscot never formally sided with the Americans during the Revolutionary War and refused to commit the tribe as a whole to the war effort but allowed some of their young men to enlist.

Some Penobscot served as scouts for Washington’s army and Penobscot warriors fought in a number of campaigns during the war, including the American campaign against Quebec in 1775 and the Penobscot Expedition in 1779.

In recognition for their service, the Penobscot were later awarded a reservation at Indian Island, Old Town, Maine around 1798.

The Abenaki, a tribe who lived in northern New England and the southern part of the Canadian Maritimes, were divided on the issue of the Revolutionary War and fought in small engagements for both the British and the Americans, according to Calloway:

“…and Abenakis served in small-scale operations on both sides during the war. But beneath the surface confusion and ambivalence, all Abenakis at all times shared the goal of preserving their community and keeping the war at arm’s length. All they disagreed on was the means to that end. Neutrality was a perilous strategy, more likely to make the village a target than a haven when British and Americans alike adhered to the notion that if Indians were not fighting for you they would fight against you. Many Abenakis opted instead for limited and sometimes equivocal involvement in the conflict. The family-band structure of Abenaki society meant that different people could espouse different allegiances without tearing the community apart. Individual participation on both sides, though limited and part of no master strategy, also allowed flexibility as the fortunes of war shifted. The Revolution would not leave the Abenakis alone, but they could divert it into less destructive channels.” (Calloway 65)

In 1777, the British recruited about 400 warriors from the Abenaki villages of Odanak, Becanour, Caughnawga, Saint Regis and Lake of the Two Mountains into Burgoyne’s campaign.

The disastrous campaign only strengthened the Abenaki’s reluctance to support the British in the war and many Abenaki began to take an anti-British stance. As a result, the Abenaki became even more divided over the war.

In 1781, American Colonel John Allen raised an Abenaki regiment at Machias which harassed British shipping along the Maine coast during the war. Meanwhile, other Abenaki served with the British and raided Maine’s Androscoggin valley.

After the war ended, only about 1,000 Abenaki remained. With the American victory in the war, more and more white settlers began to encroach on Abenaki land and various states began to buy up Abenaki land.

In the first ten years after the war, most of the Abenaki left the United States and settled in Canada. In 1805, Canada awarded the Abenaki land for a reservation.

Animosity between the Abenaki and the Americans continued into the 19th century, prompting many warriors to fight for the British in the War of 1812.

The Micmac (also spelled Mi’kmaq), a tribe with a population of around 3,000 who lived in the Canadian maritimes, allied themselves with the Americans during the Revolutionary War, hoping that overthrowing the British would restore French rule in North America.

In February of 1776, George Washington wrote a letter to the Grand Chief of the Micmac tribe asking for their assistance in the war.

Seven captains of the Micmac and three Maliseet captains responded and traveled to Watertown, Mass on July 10, 1776. Major Shaw brought these captains in his sloop from Machias, Maine to Salem, Mass where they continued their journey to Watertown in carriages provided by the military.

On July 19, 1776, the Micmac and Maliseet signed the Treaty of Watertown, which was a treaty of alliance and friendship signed between the two tribes and the United States.

In the early 1800s, the Micmacs were awarded land for a reservation in the Canadian maritimes.

Stockbridge-Mohican Tribe:

The Stockbridge-Mohican, a tribe who lived in Western Massachusetts, sided with the Americans in the Revolutionary War, even though they had been long-standing allies of the British and even served in militia units during King George’s War, the French and Indian War and Pontiac’s Uprising.

Their decision to ally themselves with the Americans was probably based on a number of factors, according to an article by Bryan Rindfleisch on the Journal of the American Revolution website:

“While such a decision likely involved a multitude of factors, one cannot get past the fact that the Mohican were completely surrounded by a settler community, known for its rabid opposition to the Stamp Act as well as for being a hotbed of activity for the Sons of Liberty. It would take no leap of the imagination to believe that the Mohican felt enormous pressure, if not the threat of intimidation and violence, to join the revolutionary movement. Yet the Stockbridge-Mohican also saw the revolution undoubtedly as an opportunity. If they sided with the American rebels and proved their loyalty, the new nation might respect or honor their attempts to reclaim lost lands and to protect their sovereignty.”

In April of 1774, the Provincial Congress of Massachusetts sent a message to Chief Solomon Wahaunwanwanmeet of the Stockbridge Nation informing him of the possibility of a war with the British and asked for continued friendly relations with his tribe. In response, Chief Solomon visited Boston and made a speech pledging the loyalty of his tribe. (Pope 17.)

The Stockbridge Mohicans went on to fight in some of the earliest battles of the war and were reportedly among the militiamen at Lexington and Concord in April of 1775, according to Rindfleisch.

Mohican warriors are said to have lined up alongside American militiamen along Battle Road and fired upon British soldiers as they marched back to Boston and then joined the militiamen in Cambridge as they besieged the British army within Boston.

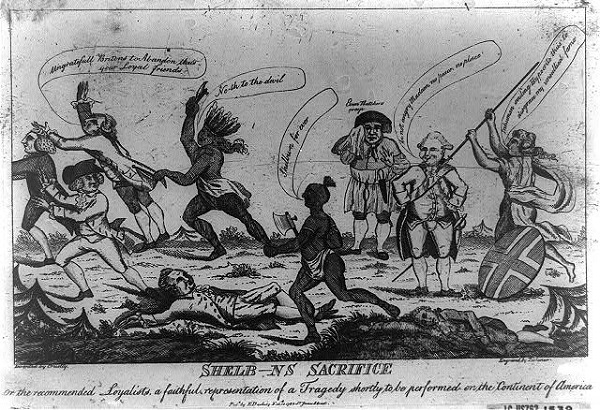

“Shelb—ns sacrifice, invented by cruelty, engraved by dishonor,” illustration depicts Lord Shelburne watching Natives slaughter loyalists in America, published in London circa 1783

During the ten-month-long Siege of Boston, the Stockbridge Mohicans helped build fortifications, patrolled the outer defenses and even conducted ambushes on British forces.

In addition, the Stockbridge Mohicans even fought in the Battle of Bunker Hill, during which a Mohican Indian, Abraham Naumanmpputaunky, was killed.

Although George Washington was reluctant to allow the Stockbridge Mohicans to officially join the Continental Army, he eventually had a change of heart and allowed them to enlist.

A regiment of Stockbridge Mohicans participated in the campaign at Valcour Bay in October of 1776, in the Saratoga campaign in 1777, they camped at Valley Forge in the winter of 1777-8 and also participated in the campaign against the Iroquois Confederacy, known as the “Sullivan Expedition,” in 1779.

The Stockbridge Mohicans were not sufficiently rewarded for their service though and their families at home went hungry and half naked, receiving no aid from the Continental Congress despite pleas on their behalf from George Washington himself.

In the meantime, white settlers continued to buy up native land in the Stockbridge area and by 1783, the Stockbridge Mohican’s had lost all of their land (Calloway 103.)

In the 1780s, the Stockbridge moved to New York to escape encroachment by white settlers in Massachusetts and lived alongside the Oneida tribe.

When the U.S. government started to buy up the Oneida land in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the Mohicans migrated to present-day Wisconsin where they were later joined by a group of the Delaware people known as the Munsee.

Finally, in 1794, the federal government signed the Treaty of Canandaigua, with the Oneida, Tuscarora, and Stockbridge, and thanked the tribes for their wartime services with a gift of $5000, a new church, grist mills and saw mills and instructions in how to operate them.

Shawnee Tribe:

The Shawnee, a tribe who lived in the Ohio River Valley. sided with the British during the Revolutionary War.

When the Revolutionary War first broke out, most Shawnee tried to remain neutral and, in early 1774, around 170 Shawnee families moved away from the Scioto River Valley to avoid getting drawn into the war.

American encroachment on Shawnee land persisted though and the tribe soon became divided on the issue. Shawnee tribes that had already allied themselves with the British threatened other Shawnee tribes with attack if they sided with the colonists.

After Chief Cornstalk was murdered by American militia in 1777, it drove many of the Shawnee to side with the British, although a number of Shawnee still tried to remain neutral. As concern over American encroachment on Shawnee land grew, more Shawnee sided with the British in the spring of 1778.

The Shawnee continued to flee Ohio and by 1779 or 1780, around 1,200 Shawnees, mostly from the Thawekila, Kispoki, and Piqua divisions, led by Yellow Hawk and Black Stump, had left Ohio and begun to migrate west to Missouri.

In May of 1779, American Colonel John Bowan launched an attack on the Shawnee town of Chillicothe during which Chief Black Fish was mortally wounded.

In the summer of 1780, when Virginia militia officer George Rogers Clark invaded the area, the Shawnee burned Chillicothe themselves to prevent it from falling to Clark.

In the fall of 1782, Clark returned to Shawnee territory and, according to Daniel Boone, who was involved in the expedition, Clark burned five villages and entirely destroyed their crops.

Just as it seemed the Shawnee were winning their war, the British lost the Revolutionary War and began trying to restrain the Shawnee warriors, urging them to make peace with the Americans as they themselves had done when they signed the Treaty of Paris and warned them that if they continued to fight with the Americans then Britain could have no part of it.

The Shawnee and the Americans continued to fight long after the war was over as more and more white settlers began to encroach on Shawnee land, according to Calloway:

“For a time during the Revolution, many Shawnees came to identify Britain’s cause as their own, and the dwindling of British support hit them hard. But the struggle that terminated for redcoats and patriots in 1783 did not end for the Shawnees. The Shawnees carried on the fight for another dozen years and took a leading role in an emerging multi-tribal confederacy.” (Calloway 49.)

Delaware Tribe:

The Delaware (also known as the Lenni Lenape), a tribe in the Ohio Valley, sided with Americans during the Revolutionary War and signed a treaty with the United States government, the Treaty of Fort Pitt, in 1778.

The Delaware were originally neutral at the outbreak of the war but quickly came under pressure from British and American agents and from other tribes, particularly the Wyandots in the north, who were pro-British.

After the deaths of chiefs Custaloga and Netawatwees in the fall of 1776, the Delaware national council found itself divided. Many Delaware chiefs argued that an alliance with the Americans was an opportunity to assert the tribe’s independence from the Six Nations and to challenge the Six Nations’ claims to lands west of the Ohio.

In 1778, the United States signed its first treaty, the Treaty of Fort Pitt, with the Delaware tribe. The treaty allowed American troops to pass through Delaware territory.

In addition, the Delaware agreed to sell meat, corn, horses and other supplies to the United States and allow their men to enlist in the United States army.

The treaty also stated that the Delaware could form their own state and have a representative in Congress, if they wanted.

The treaty created division within the tribe. Some Delaware chiefs, such as White Eyes and John Killbuck of the Turtle clan, continued to support the Americans but other chiefs, like Captain Pipe of the Wolf clan, moved his followers to the Sandusky River in northwestern Ohio to be closer to the Wayndots and the British.

After signing the treaty, Chief White Eyes died of smallpox. Yet, many Delaware Indians and some historians believe he didn’t die of smallpox and was instead murdered by an American militia group and then secretly buried.

In 1781, a force of about 300 Americans attacked the Delaware village of Coshocton, Ohio and a neighboring village of Licheneau. During the attack, the Americans captured and killed 15 Delaware warriors and were accused of using excessive cruelty in killing the captives.

In 1782, a group of Pennsylvania militiamen, incorrectly believed that the Delaware were responsible for several recent raids and killed around 100 Christian Delaware in what became known as the Gnadenhutten Massacre.

After the American victory in the Revolutionary War, the Delaware struggled as the Americans continued to move into the native’s territory and were later forced to surrender most of their Ohio lands with the Treaty of Greenville in 1795.

In 1829, the United States forced the Delawares to relinquish their remaining land in Ohio and move west of the Mississippi River.

Miami Tribe:

The Miami, a tribe in the Great Lakes region, sided with the British during the Revolutionary War.

In late October of 1780, the war came to the Miami when French cavalry officer Augustin Mottin LeBalme, who was aiding the Americans in the war, raided the Miami village of Kekionga.

After LeBalme plundered the area for 12 days, on November 5, 1780, Chief Little Turtle attacked the force and killed LeBalme and 30 of his soldiers, bringing the fight to an end.

After the British lost the war, the Miami tribe continued to fight the Americans who began pouring into the Ohio country. Between the years 1783 and 1790, the Miami tribe killed 1,500 settlers.

This sparked a war between the Americans and the Miami tribe, the Miami War, which is also known as Little Turtle’s War, from 1790-1794.

The Miami tribe were defeated and, in August of 1795, Chief Little Turtle and many other allied tribes signed the Treaty of Greenville, ceding most of their territory in Ohio and Indiana to the Americans.

Throughout the 19th century, the Miami continued to sign more treaties and ceded more land and the tribe eventually emigrated to Kansas in 1846 and were then removed to Oklahoma in 1867.

Wyandot Tribe:

The Wyandot (Huron), a tribe in the Great Lakes region, sided with the British during the Revolutionary War.

In May of 1782, American Colonel William Crawford led an expedition against the Wyandot town at Upper Sandusky upon orders of George Washington to attack local Indians who had sided with the British.

Crawford’s army was defeated and the Wyandot captured Crawford and burned him at the stake. The site of Crawford’s execution is now on the National Register of Historic Places and a monument has been erected there in his memory.

After the war, the Wyandot continued to fight the Americans who encroached on their land. There was a brief lull in the fighting from 1783-1785, and the United States, Wyandot, Delaware, Chippewa, and Ottawa tribes signed the Treaty of Fort McIntosh in 1785.

The fighting resumed shortly after though when white settlers ignored the treaty and continued to settle of Indian land. The Wyandott were eventually defeated by General Anthony Wayne at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794.

The tribe surrendered most of their lands in Ohio when they signed the Treaty of Greenville and ceded even more land in the Treaty of Detroit in 1807.

In 1843, the Wyandots were forcibly removed from their remaining land and relocated to a reservation in Kansas. After the Civil War, the Ohio Wyandot were relocated to Oklahoma.

Iroquois Confederacy:

The Iroquois Confederacy, also known as the Six Nations, was an alliance of six tribes in New York and Canada: the Mohawks, Oneidas, Tuscaroras, Onondagas, Cayugas and Senecas.

The Iroquois Confederacy had been long-standing allies of the British. Yet, when the Revolutionary War broke out, the confederacy split in two when the Onondagas, Cayugas, Senecas and Mohawks sided with the British, while the Tuscarora and the Oneida sided with the Americans.

In the early years of the war, many Iroquois towns in the Mohawk and Susquehanna valleys were attacked by American troops in retaliation for siding with the British.

On March 6, 1779, George Washington stated in a letter to Major General Horatio Gates “to carry the war into the heart of the country of the six nations; to cut off their settlements, destroy their next year’s crops, and do them every other mischief of which time and circumstances will permit.”

On May 31, 1779, Washington wrote a letter to Major General John Sullivan advising him how to carry out these orders against the Iroquois Confederacy:

“The expedition you are appointed to command is to be directed against the hostile tribes of the six nations of Indians, with their associates and adherents. The immediate objects are the total destruction and devastation of their settlements and the capture of as many prisoners of every age and sex as possible. It will be essential to ruin their crops now in the ground and prevent their planting more.”

Washington went on to add that if the natives indicate they want peace, they must earn it:

“After you have very thoroughly completed the destruction of their settlements; if the Indians should show a disposition for peace, I would have you to encourage it, on condition that they will give some decisive evidence of their sincerity by delivering up some of the principal instigators of their past hostility into our hands—Butler, Brandt, the most mischievous of the tories that have joined them or any other they may have in their power that we are interested to get into ours…”

That spring, American Colonel Goose Van Schaick raided the Onondaga settlements, destroying their crops and towns, slaughtering their livestock and capturing 33 prisoners.

In the fall of 1779, American General John Sullivan led his campaign of destruction, known as the “Sullivan Expedition,” in the Iroquois country by burning 40 towns, 160,000 bushels of corn and vegetables.

Meanwhile, American General Daniel Brodhead and his 600 men attacked the western Iroquois towns, burning and plundering the Seneca and Munsee towns on the Allegheny.

The destruction in Iroquois country was so great that many Iroquois had to flee to Canada and subsist on British charity there.

The tribes that did side with the Americans, such as the Oneida, didn’t fare much better because they suffered retaliation from the pro-British tribes of the confederacy.

The Oneida, a tribe in the Iroquois Confederacy who lived in western New York, originally tried to remain neutral during the early years of the war but, in 1775, they sided with the Americans. The Tuscarora also sided with the Americans, most likely due to their close relationship with the Oneida.

Some historians believe this Oneida-Colonist alliance was due to the efforts of the Oneida’s Presbyterian missionary Samuel Kirkland but other historians argue that it was more likely due to a series of factors, including gradual Europianization of the Oneida, strong ties between the Oneida and the colonists, and a gradual weakening of the Iroquois Confederacy.

The decision of the Oneida to support the Americans split the Iroquois Confederacy and eventually even split the Oneida tribe itself. As the war raged on, opposing sides of the Iroquois Confederacy began to turn on each other, according to Calloway:

“Pro-British warriors burned Oneida crops and houses in revenge; Oneidas retaliated by burning Mohawk homes. The Oneidas themselves split into factions; most supported by the Americans, whereas the Cayugas lent their weight to the crown. The Onondagas struggled to maintain neutrality until American troops burned their towns in 1779. For the Iroquois, the Revolution was a war in which, in some cases literally, brother killed brother. ” (Calloway 33-34.)

The Oneida went on to fight in several key battles in the war, including the battles of Oriskany, and Saratoga and their support was considered a crucial factor in preventing an early American defeat in New York state and in the war in general.

On October 22, 1784, the Fort Stanwix Treaty formally brought the fighting between the Americans the Iroquois Confederacy to an end. The treaty awarded peace and government protection to the Senecas, Mohawks, Onondoagas and Cayugas on the following conditions:

1. Six hostages shall be immediately delivered to the commissioners by the tribes until all the prisoners taken by the tribes are returned.

2. The Oneida and Tuscaroras “shall be secured in the possession of the lands on which they are settled.”

3. Boundaries for the Six Nation’s lands should be clearly drawn in the area indicated in the treaty.

4. The Commissioner of the United States will order goods to be delivered to the Six Nations for their use.

On December 2, 1794, the Oneida’s wartime service was formally recognized by the U.S. Congress with the Treaty of Canandaigua, a document signed by President George Washington that affirmed the tribe’s right to oversee their affairs and lands without interference from other governments.

In addition, the Oneidas, Tuscaroras, and Stockbridge Indians were promised a new church in addition to grist mills and saw mills and instructions in how to operate them. The tribes, in return, promised to relinquish all other claims for compensation and rewards.

Potawami Tribe:

The Potawami, a tribe in the Great Lakes region, tried to remain neutral in the Revolutionary War but eventually sided with the Americans in 1778.

The Potawami had been long-standing trading partners and military allies with the French and fought alongside them in the French and Indian War but were reluctant to get involved in another war.

In 1778, a Virginia militia officer, George Rogers Clark, brought a small army to Illinois and conquered the Midwest. Clark met with Siggenauk, a Potawami chief from Milwaukee, and convinced him to join the American’s side in the Revolutionary War, according to an article on the Milwaukee Public Museum website:

“Along with another Milwaukee Potawatomi, Naakewoin, Siggenauk effected a diplomatic coup over the course of the next two years and managed to turn Potawatomi villages around the southern shore of Lake Michigan against the British. When the British tried to recruit local Indians for their cause, they made little headway.”

In 1780, Chiefs Siggenauk and Naakewoin attacked a British force of Indians and French Canadians.

In 1781, Chief Siggenauk led an Indian force from St. Louis and attacked a British post in southwestern Michigan.

When the Americans won the war, they took the entire Midwest from the British in the Treaty of Paris in 1783.

As more and more white settlers began to move into the Ohio River Valley, the Ohio Indians found themselves in a war with the United States from 1790 to 1794. Many Potawatomi fought in this war against the Americans and the war turned many Indians against the United States, including Siggenauk.

In the early 19th century, the Shawnee joined a pan-Indian military alliance that fought with the British during the War of 1812 but the Shawnee eventually lost their stronghold on Wisconsin and other parts of the Midwest when the British lost the war and had to return their conquered lands.

After falling on hard times, the Potawatomi had ceded much of their lands to the United States by the mid-19th century and the tribe split up and relocated to various distant locations, such as Texas, Kansas, Iowa and Canada, although many stayed in Wisconsin.

Catawaba Tribe:

The Catawaba, a tribe with a population of a few hundred that lived in the Piedmont area along the border of South Carolina and North Carolina, sided with the Americans in 1775.

The Catawaba fought in numerous key battles in South and North Carolina, such as the 1776 campaign against the Cherokee, the Battle of Haw River in North Carolina, the battles of Fishing Creek and Rocky Mount in South Carolina, the Battle of Hanging Rock in South Carolina and the Battle of Eutaw Spring in 1781.

In 1780, the British invaded the South and the Catawaba villages became a temporary refuge for American troops. But the British troops eventually forced the Catawaba to flee north to Virginia when they burned their villages and confiscated their cattle and other goods.

In 1782, after General Charles Cornwallis surrendered at Yorktown, the Catawaba returned home and the South Carolinians paid them for their service.

The Catawbas also received a state-recognized reservation in South Carolina as a result of their support of the Americans, which they still occupy today.

Chickasaw Tribe:

The Chickasaw, a southern tribe with a population of 4,000 who lived in Mississippi, Alabama, Tennessee, Kentucky and Missouri, sided with the British during the Revolutionary War.

The Chickasaw had been trading partners and staunch allies of the British throughout the 18th century and continued their support for the British in the Revolutionary War.

The Chickasaw participated in the war mostly by patrolling the Mississippi River against American attacks and engaging in battles against American Colonel George Rogers Clark in present-day Illinois. Small groups of Chickasaw warriors also helped Britain defend Mobile and Pensacola against the Spanish in 1780-81.

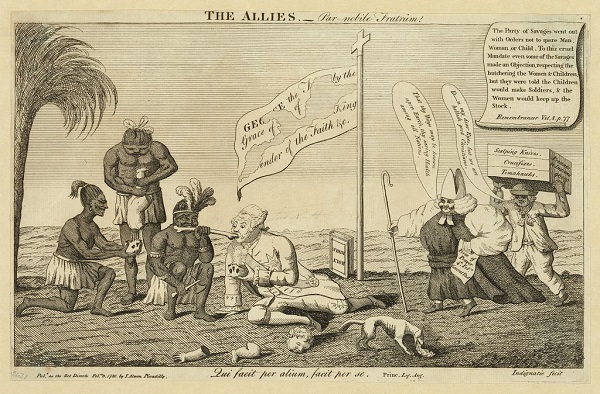

The allies – A Splendid Pair, illustration by John Almon showing King George III sharing a bone with a Native, published circa 1780

After the war ended, the Chickasaws lost the British as trading partners and were forced to seek trade with Spain and the United States.

Choctaw Tribe:

The Choctaw, a southern tribe with a population of 15,000 who inhabited about 50 villages in a key strategic position of the lower Mississippi, were coveted by both the Americans and the British during the Revolutionary War but the tribe sided with the British.

At the start of the Revolutionary War, the British hired Choctaw warriors to patrol the Mississippi River against American attacks.

In February of 1778, American Captain James Willing led an expedition down the river attacking British settlements all the way down to New Orleans. The British responded by organizing a band of 155 Choctaw warriors to march to one of the settlements under threat, Natchez, to protect it.

The Americans had retreated by the time the Choctaw reached Natchez but they managed to convince the Natchez residents to remain pro-British.

After Spain declared war on Britain, hundreds of Choctaw warriors helped the British defend Mobile in 1780 and Pensacola in 1780-81, even though a small faction of Choctaw warriors supported Spain.

After the British lost the war, the Choctaw lost the British as trading partners and were forced to seek trade with Spain and the United States.

Creek Tribe:

The Creek, a southern tribe with a population of 15,000 that lived in Georgia, Alabama, Florida, and North Carolina, never officially joined the war effort, preferring instead to engage in cautious participation.

Factionalism within the tribe was a major factor in preventing the tribe from unifying and joining the war effort. Creek towns were divided among the Lower Towns and Upper Towns, with each town asserting its own foreign policies.

Access to European manufactured goods were the Creek’s biggest concern and the war put trade relations in jeopardy.

Yet, the war also provided Creek men with the ability to acquire trade goods by providing military services, especially in the Mobile and Pensacola campaigns between Britain and Spain in 1780–81.

Still other Creeks used the war to strengthen their political positions by taking leadership roles in diplomacy.

Nevertheless, the Creek tribe never engaged in significant sustained fighting during the war.

Cherokee Tribe:

The Cherokee, a southern tribe with a population of about 8,500 who lived in the interior hill country of the Carolinas and Georgia, sided with the British during the Revolutionary War.

In the spring of 1776, young warriors, led by Cherokee Chief Dragging Canoe, launched attacks on the American frontier in the Carolinas and Georgia in retaliation for illegal encroachments on their lands, according to an article on the Encyclopedia of Alabama website:

“The willingness of Dragging Canoe and other warriors to take the fight to white settlers stemmed in part from a generational split among the Cherokees: young warriors increasingly distrusted their elders’ abilities to prevent further land loss.”

In response, the colonial governments of Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia organized retaliatory expeditions against the Cherokees.

During the summer and fall of 1776, they invade and burned nearly all of the local Cherokee villages, in what became known as the Cherokee War of 1776.

In August of 1776, American Colonel Andrew Williamson, with 1,800 troops and some Catawba scouts, marched to northwestern South Carolina, burning Cherokee villages along the way.

In September of 1776, American General Griffith Rutherford attacked the Cherokee Middle settlements from North Carolina and destroyed 36 towns, along with livestock and cornfields while Williamson attacked the Lower towns with his soldiers.

The two generals then joined forces and spent two weeks attacking and destroying the Cherokee Middle settlements while American Colonel William Christian and his 2,000 Virginia and North Carolina militiamen invaded the Cherokee Overhill towns, destroying their crops, apple trees, houses and food supplies.

In 1777, the older Cherokee chiefs began pushing for peace, while Dragging Canoe and hundreds of other Cherokees moved south and west to establish new villages on Chickamauga Creek. The tribe soon became divided on the issue, according to Calloway:

“Refugee Cherokees fled to the Creeks, the Chickasaws, and to Penscola. The nation split along generational lines as many younger warriors followed the lead by Dragging Canoe. Some five hundred families seceded to form new communities on the Chickamauga River. The Chickamauga towns became the core of the Cherokee resistance, attracting warriors from other towns and supporting the war effort of the Shawnees and their northern allies. Other Cherokees suffered as a result of Chickamauga resistance, some helped the Americans, and the Revolution became a Cherokee civil war” (Calloway 44.)

The American troops continued their attacks on Cherokee towns. In April of 1779, American Colonel Ethan Shelby invaded Chickamauga Cherokee country inflicting catastrophic damage, according to Thomas Jefferson, by “killing about a half dozen men, burning 11 towns, 20,000 bushels of corn…and taking as many goods as sold for twenty-five thousand pounds.”

In the summer of 1779, British agent Alexander Cameron planned to raise a Cherokee force as soon as the crops were harvested but, in the meantime, American Brigadier General Andrew Williamson and 700 cavalrymen invaded Cherokee country.

Two Cherokee chiefs were sent to negotiate with Williamson, who agreed to spare their cornfields if the Cherokees handed over Cameron. When they refused, Williamson burned down their houses and cut down their corn.

In December of 1780, American Colonel Arthur Campbell burned around 1,000 houses and 50,000 bushels of corn belonging to the Overhill Cherokee.

In 1781, American Lieutenant Colonel Jon Sevier of the North Carolina militia destroyed fifteen Middle Cherokee towns and, the following fall and summer, destroyed new Lower Cherokee towns on the Coosa River.

Also in 1781, Andrew Picken’s South Carolina militia killed fleeing Cherokee during a raid on a Cherokee settlement.

The Cherokee’s price for taking the British side in the war was disastrous, according to Calloway:

“A Cherokee headman summed up the cost to his people of supporting the British against ‘the madmen of Virginia’: ‘I…have lost in different engagements six hundred warriors, my towns have been thrice destroyed and my corn fields laid waste by the enemy” (Calloway 50.)

Sources:

Worthington, Don. “Catawba Indians Sided with Colonists in Revolutionary War.” The Herald, 3 July. 2015, www.heraldonline.com/news/local/article26418919.html

Pope, Franklin Leonard. The Western Boundary of Massachusetts: A Study of Indians and Colonial History. Privately Printed, 1886.

Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico. Edited by Frederick Webb Hodge, Vol. 1, Washington Government Printing Office, 1907.

“Wyandot Indians.” Ohio History Central, www.ohiohistorycentral.org/w/Wyandot_Indians

“Colonel William Crawford Proceeds to the Ohio.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 13 Nov. 2009, www.history.com/this-day-in-history/colonel-william-crawford-proceeds-toward-the-ohio

Levinson, David. “An Explanation for the Oneida-Colonist Alliance in the American Revolution.” Ethnohistory, vol. 23, no. 3, 1976, pp. 265–289. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/481255.

Smith, Nicholas. “Passamaquoddy Indian Papers,1775-1912.” Cornell University, rmc.library.cornell.edu/EAD/htmldocs/RMM09014.html

Rindfleisch, Bryan. “The Stockbridge -Mohican Community, 1775-1783.” Journal of the American Revolution, 3 Feb. 2016, allthingsliberty.com/2016/02/the-stockbridge-mohican-community-1775-1783/

“The Treaty of Watertown.” The Historical Society of Watertown, historicalsocietyofwatertownma.org/HSW/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=86

“The American Revolution.” Clarke Historical Library, www.cmich.edu/library/clarke/ResearchResources/Michigan_Material_Local/Detroit_Pre_statehood_Descriptions/A_Brief_History_of_Detroit/Pages/The-American-Revolution.aspx

“Micmac History.” Dickshovel.com, www.dickshovel.com/mic.html

“Abenaki History.” Tolatsga.org, www.tolatsga.org/aben.html

“Maine Indians and the Revolutionary War.” Native Heritage Project, 23 March. 2012, nativeheritageproject.com/2012/03/23/maine-indians-and-the-revolutionary-war/

“Revolutionary War.” Oneida Indian Nation, www.oneidaindiannation.com/revolutionarywar/

“Miami Nation of Oklahoma Study Notes.” Miami University, www.users.miamioh.edu/johnso58/246SNmiami.html

“Miami Indians.” Michigan State University, Department of Geography, Environment , & Spatial Sciences, geo.msu.edu/extra/geogmich/Miamis.html

Gen. George Washington to Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates, March 6, 1779, John C. Fitzpatrick, ed. Writings of George Washington (Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1936), 14:198-200.

O’Brien, Greg. “Southeastern Indians and the American Revolution.” Encyclopedia of Alabama, www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-1133

“From General George Washington to Major General John Sullivan, 31 May 1779.” Founders Online,

founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-20-02-0661

Calloway, Colin G. “‘We Have Always Been the Frontier’: The American Revolution in Shawnee Country.” American Indian Quarterly, vol. 16, no. 1, 1992, pp. 39–52. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1185604.

Calloway, Colin G. The American Revolution in Indian Country: Crisis and Diversity in Native American Communities. Cambridge University Press, 1995.

“Journals of the Continental Congress – Speech to the Six Nations; July 13, 1775.” The Avalon Project, Yale Law School, avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/contcong_07-13-75.asp

“Potawatomi History.” Milwaukee Public Museum, www.mpm.edu/content/wirp/ICW-152.html

“The Native American’s Roles in the American Revolution: Choosing Sides.” Edsitement!, National Endowment for the Humanities, edsitement.neh.gov/lesson-plan/native-americans-role-american-revolution-choosing-sides#sect-background

Schmidt, Ethan A. Native Americans in the American Revolution. Praeger, 2014.

Calloway, G. Collin. “The American Revolution.” NPS.gov, National Parks Service, www.nps.gov/revwar/about_the_revolution/american_indians.html

Thanks for helping with my assingment

Thanks for helping my homework!!

Thanks for helping me and my group!

This is an excellent research effort. It shows the magnitude and importance of the Native American involvement in our country’s battle for independence, not just in New England, but throughout the colonies. Unfortunately, our country repaid their loyalty and services, not by treating them as allies deserving of our immense gratitude and thanks, but by treating them as enemies to be feared and destroyed. Federal and state governments took every opportunity to remove tribes from their lands, destroy their culture and humiliate them. This has continued up to the present day, where it is almost impossible to find anyone in federal or state government that will acknowledge in any meaningful way the vital service these Native Americans provided to our country in its first and gravest critical hour of need. In an irony of ironies the federal government, the state of Maine and other states have argued vigouroly since 1776 that some of these same tribes that fought with General Washington were never “recognized” as tribal governments by the United States, despite the evidence you cite, and therefore do not deserve to be accorded the rights of Native American tribes in the US.

Great resource!! Helped me a lot with my essay!!