The economy of Plymouth Colony was based on agriculture, fishing, whaling, timber and fur.

The Plymouth Company investors initially invested about £1200 to £1600 in the colony before the Mayflower even sailed. The colonists had to pay this money back over seven years by harvesting supplies and shipping them back to the investors in England to be sold.

Each investor in the Plymouth Company was issued shares worth £10 and each adult colonist received one share and were given options to purchase more shares later on. For the first seven years, everything was to remain in the “common stock” which was owned by all the shareholders.

The common stock helped supply the colonists with things like food, tools and clothing. At the end of the seven years, the shareholders would divide the profits and capital (which included houses, land and goods) equally.

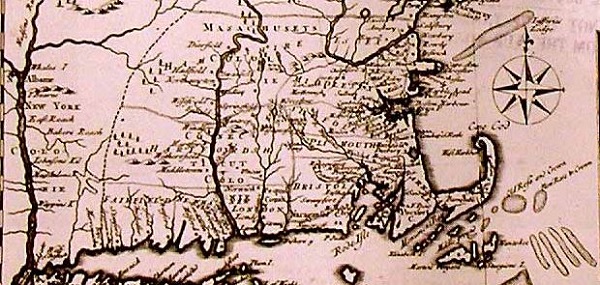

Plymouth on a map of New England, circa 1720

Yet, in 1623, the common-stock plan was abandoned and the land and houses were divided so that each colonist could reap the rewards of their own labor.

The colony had been barely producing enough food to survive and the Governor of the colony, William Bradford, felt that the communal aspect of the colony was discouraging many of the colonists from working hard because they felt they were working for others rather than themselves.

When the common-stock plan was abandoned and the new plan put into place, the colony suddenly began to flourish and they soon had an abundance of food. Corn production dramatically increased and famine was averted.

Bradford described in his diary, which was later published under the title Of Plymouth Plantation, the reasoning behind the change of plans and why it worked:

“The experience that was had in this common course and condition, tried sundry years and that amongst godly and sober men, may well evince the vanity of that conceit of Plato’s and other ancients applauded by some of later times; that the taking away of property and bringing in community into a commonwealth would make them happy and flourishing; as if they were wiser than God. For this community (so far as it was) was found to breed much confusion and discontent and retard much employment that would have been to their benefit and comfort. For the young men, that were most able and fit for labour and service, did repine that they should spend their time and strength to work for other men’s wives and children without any recompense. The strong, or man of parts, had no more division of victuals and clothes than he that was weak and not able to do a quarter than the other could; this was thought injustice. The aged and graver men to be ranked and equalized in labours, victuals, clothes, etc., with the meaner and younger sort, thought it some indignity and disrespect unto them. And for men’s wives to be commanded to do service for other men, as dressing their meat, washing their clothes, etc., they deemed it a kind of slavery, neither could many husbands well brook it.”

The fur trade industry was the colony’s economic salvation. For the first few years that the colony existed, the colonists struggled to make enough money to pay the investors back. In fact, they had to ask for more money just to keep the colony running and by the mid to late 1620s, they were deeply in debt to the investors.

To help pay down the debt they still owed, the colonists established a beaver fur trading base in Kennebec, Maine by 1625. Beaver were plentiful in Maine where the local Native-Americans tribe had hunted them for generations.

This fur trading business was very successful for the colonists and quickly became an essential part of their economy. Their success in this trade continued well into the 1630s and 1640s but by the 1650s beaver became scarce in New England.

Unable to expand their hunting grounds due to pressure from other colonies, the colonists finally sold their land in Kennebec in the 1660s and fish and lumber eventually became the staples of the colony’s economy.

According to the book Cape Cod and Plymouth Colony in the 17th Century, whaling was a particularly vital part of the economy in Plymouth:

“The whale processed on Cape Cod were Atlantic right whales, so called because they were the correct, or ‘right,’ whales for human use. They were a coastal, migratory whale, which floated when dead, and produced a good quality oil. Most of the whales utilized by Seventeenth-century Cape Codders were beached whales, which had run aground themselves. Other whales were taken directly at sea. Some were killed at sea or driven on to the shore from boats, and others were ‘drift’ whales which had died at sea and were later hauled to shore. Over the century, the number of whales increased, as efforts to kill them at sea failed, and their wounded or dead carcasses later washed up on the shore. However obtained, whales, and especially their oil, were an important item in the economy of Plymouth Colony. Despite whale’s obvious economic significance, the historical sources are strangely silent respecting their number and processing, and it is difficult to determine how much oil a particular whale would yield. The official records are similarly of little help, referring only to whale oil owed to the colony or to those who processed it for the town. One clue comes from Edward Randolph. Writing to England in January 1687/88, he estimated Plymouth had exported two hundred tons of whale oil in the previous months, and predicted that whale oil would replace the fur trade as a staple of the colony’s economy. Another comes from Wait-Still Winthrop. In a letter to his brother he mentioned a report of twenty-nine whales having been killed in one day, and that on a previous visit to Plymouth he had learned of a group who had killed six whales within a few days. Offsetting these rather generous estimates, is Thomas Hinckley’s reference to small whales which produced between seven and twenty barrels of oil.”

Woodcut depicting whaling in the 16th century

In 1627, the Plymouth Company investors were unhappy with the lack of return they saw from the colony and the colonists agreed to buy them out for £1800, which was to be paid in installments of 200 pounds a year over nine years.

Eight colonists pledged their personal credit to buy the investor’s shares. These colonists were William Bradford, John Howland, Myles Standish, Isaac Allerton, Edward Winslow, William Brewster, John Alden and Thomas Prence.

In reality, it took much longer than nine years to pay back the money and the pilgrims didn’t finish paying it off until over 20 years later in 1648.

Ultimately, Plymouth colony never achieved the level of economic success that its neighbor, the Massachusetts Bay Colony, did and was eventually merged with the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1691 and became a royal colony known as the Province of Massachusetts Bay.

For more information about Plymouth Colony, here are some related articles: The Government of Plymouth Colony and Religion in Plymouth Colony.

Sources:

Wilkins, Mira. The History of Foreign Investment in the United States to 1914. Harvard University Press, 1989.

King, H. Roger. Cape Cod and Plymouth Colony in the Seventeenth Century. University Press of America, 1994.

“Beyond the Pilgrim Story.” Pilgrim Hall Museum, www.pilgrimhallmuseum.org/bradford_17th_century_documents.htm

“Why the Pilgrims Abandoned Communism.” Free Republic, 22 Nov. 2004, www.freerepublic.com/focus/f-news/1285981/posts

Bower, Jerry. “Occupy Plymouth Colony: How a Failed Commune Led to Thanksgiving;.” Forbes, 23 Nov. 2011, www.forbes.com/sites/jerrybowyer/2011/11/23/occupy-plymouth-colony-how-a-failed-commune-led-to-thanksgiving/#192076afbcd1

McIntyre, Ruth. “What You Didn’t Know About the Pilgrims: They Had Massive Debt.” PBS.org, Public Broadcast Service, 2 Nov. 2015, www.pbs.org/newshour/making-sense/what-you-didnt-know-about-the-pilgrims-they-had-massive-debt/

“Were Pilgrims America’s Original Economic Migrants?.” PBS.org, Public Broadcast Service, 26 Nov. 2015, www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/were-pilgrims-americas-original-economic-migrants/

“The Pilgrims and the Fur Trade.” Pilgrim Hall Museum, www.pilgrimhallmuseum.org/pdf/The_Pilgrims_Fur_Trade.pdf

very helpful,thank you