When the puritans came to the New World, they brought with them their strict ways, their religious views and their distaste for Christmas.

Although Christmas was widely celebrated in Europe as a Christian holiday marking the birth of Jesus Christ, puritans saw it as a false holiday with stronger ties to paganism than Christianity, and they were correct, according to the book The Battle for Christmas:

“It was only in the fourth century that the Church officially decided to observe Christmas on December 25. And this date was chosen not for religious reasons but simply because it happened to mark the approximate arrival of the winter solstice, an event that was celebrated long before the advent of Christianity. The puritans were correct when they pointed out – and they pointed it out often – that Christmas was nothing but a pagan festival covered with a Christian veneer. The Reverend Increase Mather of Boston, for example, accurately observed in 1687 that the early Christians who first observed the Nativity on December 25 did not do so ‘thinking that Christ was born in that month, but because the Heathens Saturnalia was at that time kept in Rome, and they were willing to have those Pagan holidays metamorphosed into Christian ones.’”

As pious and reserved Christians, puritans also took a dislike to the drinking, dancing and gluttony associated with the holiday at the time. Christmas in Europe back then marked the end of a long year of hard work and coincided with the time of year when there was plenty of freshly fermented beer or wine and lots of freshly slaughtered meat that had to be consumed before it spoiled.

As a result, the Christmas season was often celebrated with rowdy behavior, binge eating and drinking, public drunkenness and aggressive begging (in the form of wassailing, which was the custom of going door to door singing carols in exchange for food or drink.

On some occasions the carolers would become rowdy and invade wealthy homes demanding food and drink and would vandalize the home if the owner refused.)

After the puritans left Europe, they decided to leave these holiday traditions behind. Instead of feasting and giving gifts, puritans commemorated Christmas by praying, reflecting on sin and working instead of resting.

The puritans even forced non-puritan colonists, such as the Anglicans, to work on Christmas day.

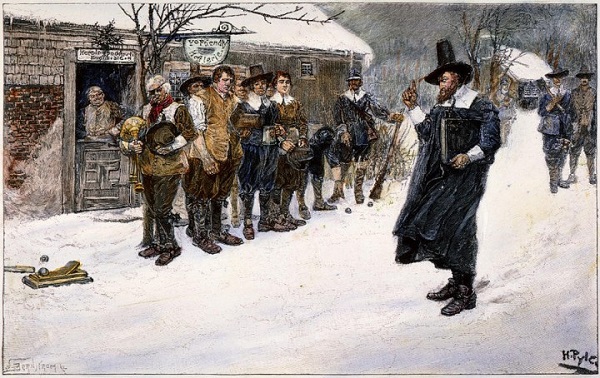

The Puritan Governor interrupting the Christmas Sports, illustration by Howard Pyle, circa 1883

In his journal, Of Plymouth Plantation, William Bradford recorded a disagreement that ensued between him and some newly arrived non-puritan colonists on Christmas day in 1621:

“One the day called Christmas day, the Gov called them out to work, (as was used,) but the most of this new-company excused them selves and said it went against their consciences to work on that day. So the Gov r told them that if they made it mater of conscience, he would spare them till they were better informed. … [Later] he found them in the street at play, openly; some pitching the barr and some at stoole-ball, and such like sports. So he went to them, and took away their implements, and told them that was against his conscience, that they should play and others work. If they made the keeping of it mater of devotion, let them keep their houses, but there should be no gaming or revelling in the streets. Since which time nothing hath been attempted that way, at least openly.”

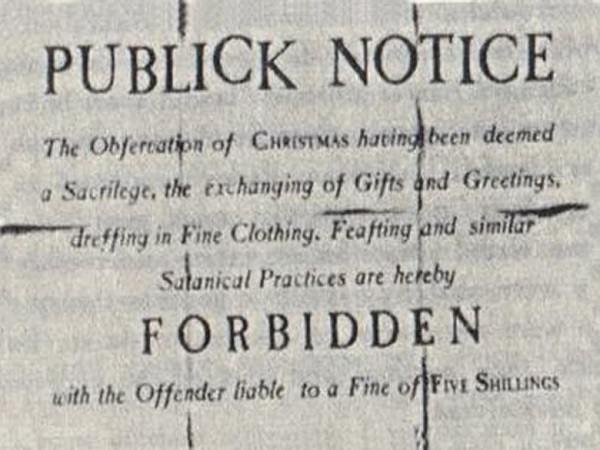

On May 11, 1659, the Massachusetts Bay Colony legislature even went so far as to officially ban Christmas and gave anyone found celebrating it a fine of five shillings:

“For preventing disorders arising in several places within this jurisdiction, by reason of some still observing such festivals as were superstitiously kept in other countries, to the great dishonor of God & offense of others, it is therefore ordered … that whosoever shall be found observing any such day as Christmas or the like, either by for-bearing of labor, feasting, or any other way, upon any such account as aforesaid, every such person so offending shall pay for every such offense five shillings, as a fine to the county” (Charters and General Laws of the Colony 119; Records of the Governor and Company of the Massachusetts Bay 366).

The ban remained in place for 22 years until it was repealed in 1681 after a new surge of European immigrants brought a demand for the holiday.

A 1659 public notice about the ban on Christmas celebrations

Even though the ban was lifted, Christmas was not warmly embraced by the puritans and it remained a dull and muted holiday over two centuries later.

In December of 1686, after the Massachusetts Bay Colony was merged with the other New England colonies to create the Dominion of New England, the newly appointed governor, Edmund Andros, offended the puritan colonists by attending Christmas services, according to the book A History of the United States:

“To the Puritans the observance of Christmas savored of popery, but Andros attended service on that day, morning and afternoon, ‘a redcoat going on his right hand and Captain George on his left,’ with sixty red-coated soldiers following on. [Samuel] Sewall relates with some satisfaction that the shops, nevertheless, were generally open and the people about their occasion.”

In the early 1800s, a religious revival spurred a renewed interest in Christmas. The holiday became popular again in the South, but it was slow to catch on in New England.

In 1830, Louisiana was the first state to make Christmas a holiday. Other states followed suit and Christmas soon became popular again, especially during the Civil War.

In 1856, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote “We are in a transition state about Christmas here in New England. The old Puritan feeling prevents it from being a cheerful hearty holiday; though every year makes it more so.”

Later that year, the Massachusetts legislature finally made Christmas an official holiday in the state. Finally, in 1870, President Ulysses S. Grant made Christmas a national holiday.

Sources:

Records of the Governor and Company of the Massachusetts Bay in New England. Edited by Nathaniel B. Shurtleff, vol. 4, pt. 1, Boston: Commonwealth of Massachusetts, 1854.

The Charters and General Laws of the Colony and Province of Massachusetts Bay. Boston: T.B. Wait and Co, 1814.

Nissenbaum, Stephen. The Battle for Christmas: A Social and Cultural History for Our Most Cherished History. Vintage Books, 1996

Channing, Edward. A History of the United States: A Century of Colonial History, 1660-1760. Macmillan Company, 1908.

“Christmas Was Once Banned in Boston.” The Day, 20. Dec. 1971, news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1915&dat=19711215&id=h_AgAAAAIBAJ&sjid=1XMFAAAAIBAJ&pg=2146,3635821

Marriott, Dana P. “When Christmas Was Banned in Boston.” American Heritage, www.americanheritage.com/content/when-christmas-was-banned-boston

This is true, but they were all Puritans (although different kinds) and they all disliked Christmas.

This won’t be intellectually deep, but what happened with “separation of church and state”…,”freedom of religion”?

Could you source that “1659 proclamation”? I can’t find it anywhere and I suspect it is created.

Done.