The Battle of Bunker Hill was one of the early battles of the Revolutionary War and the most significant battle of the Siege of Boston.

The Siege of Boston began after the Shot Heard Round the World took place in April of 1775 and the British retreated back to Boston where they were trapped inside the city by the rebels.

The following are some facts about the Battle of Bunker Hill:

What Was the Battle of Bunker Hill?

The Battle of Bunker Hill was a military conflict between the American colonists and the British government during the Revolutionary War.

What Year Was the Battle of Bunker Hill?

The Battle of Bunker Hill took place on June 17 in 1775.

Where Was the Battle of Bunker Hill Fought?

The battle was fought on Breed’s Hill in Charlestown, Massachusetts.

What Caused the Battle of Bunker Hill?

The battle started after colonists heard of the British army’s plans to take control of the hills of Charlestown and Dorchester and attack rebel posts in Roxbury and Cambridge in an attempt to end the siege, according to the book Decisive Day: The Battle for Bunker Hill:

“[General] Howe outlined the plan in a letter written on June 12 to his brother, the admiral. First, a detachment would move out against Dorchester neck, throw up two redoubts there, and then attack the rebel post in Roxbury. Once Boston was safe from attack in that direction, Howe would take a large force to Charlestown heights and either attack the Americans in Cambridge or outflank that post, which would accomplish the same purpose. ‘I suppose the rebels will move from Cambridge,’ Howe added confidently, ‘and that we shall take and keep possession of it.’ The attack was set for June 18.”

The British troops had been blockaded inside Boston by the American troops since the Siege of Boston began on April 19, 1775. The British army felt that if it could take control of the hills surrounding Boston, they could break the blockade and have complete control of Boston.

The colonists found out about the plan accidentally when an unidentified New Hampshire resident happened to learn of it in a conversation with a British officer and later reported it when he returned home to New Hampshire.

The issue was raised on June 13 at the Committee of Safety meeting in Exeter, New Hampshire, and word was quickly sent to the American troops in Boston.

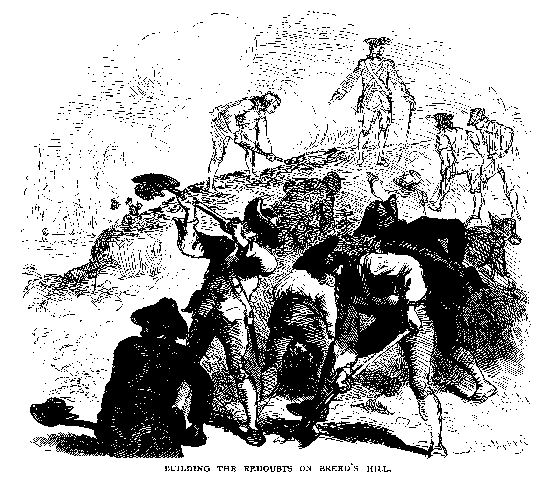

To prevent the British troops from carrying out the plan, Colonel William Prescott and his men marched to nearby Breed’s Hill, although they were originally ordered to go to Bunker Hill, on the night of June 16 and hastily built a large earthen fortification.

It is not known exactly why the troops ended up on Breed’s hill instead of Bunker hill except that Prescott, Colonel Gridley and the other field officers decided it was a better location for their fortification, according to the book Battle of Bunker Hill:

“The order was explicit as to Bunker Hill; and yet a position in the pastures nearer Boston, now known as Breed’s hill, seemed better adapted to the objects of the expedition, and better suited the daring spirit of the officers.”

Despite the fact that the battle took place on Breed’s Hill, it still came to be known as the Battle of Bunker Hill.

Colonel Prescott troops consisted of somewhere between 1,200-1,500 men, including General Joseph Warren, General Israel Putnam and General Henry Burbeck, who had helped make ammunition for the battle alongside his father Lieutenant-Colonel William Burbeck.

When the British military saw the fortification on the hill in the early morning light, one of their ships anchored in Boston harbor, the “Lively,” opened fire on it but did not cause much damage.

The ship was ordered to cease fire but Prescott’s troops quickly came under fire again from a battery of guns and howitzers on Copp’s hill, to little avail.

At about 3 p.m., over 2,000 British infantry soldiers arrived in Charlestown village and found themselves under sniper fire from the village. In an attempt to clear out the snipers, British troops set fire to the town and burned it to the ground.

British General William Howe ordered the troops to meet at the base of the Breed’s hill, clad in their bright red coats and carrying heavy equipment and bayonets, and charge towards the colonists through the open fields on the hillside.

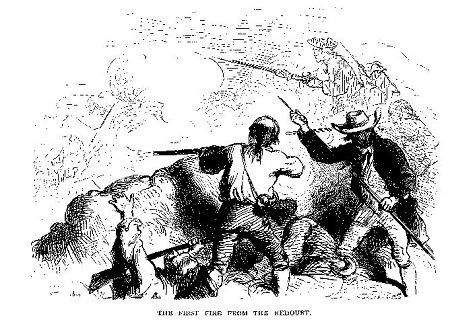

As the colonists watched their slow advance, Colonel Prescott, realizing his men were low on ammunition, allegedly gave his famous order: “Don’t shoot until you see the whites of their eyes.”

When the soldiers were within 150 feet of the redoubt, the colonists opened fire. The British took heavy losses from this first round of fire and retreated back down the hill.

After regrouping, the British made a second charge up the hill but were again thwarted by heavy fire and retreat.

After waiting an hour, the British received 400 more soldiers from Boston and made a third, and final, attempt at taking the hill, just as the colonists ran out of ammunition.

The battle was then reduced to close combat, during which many soldiers fought with nothing more than rocks and the butts of their guns, and the British finally took control of the hill.

Defeated and defenseless, the colonists retreated back up the Charlestown peninsula to Cambridge.

Battle of Bunker Hill Casualties:

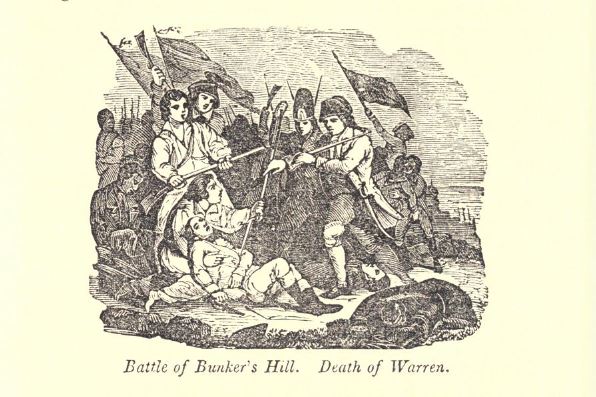

The colonists suffered most of their casualties, including the death of patriot leader Joseph Warren, not during the battle but during the retreat.

The exact whereabouts of Warren after the battle was unknown but when he failed to reappear after the retreat, the colonists assumed he was killed in action.

Warren had in fact died from a shot through the head and British soldiers buried him on the hill in a shallow grave with another colonist.

After the British left Boston in March of 1776, Warren’s body was dug up and identified by Paul Revere who recognized Warren’s two false teeth, which he had installed with a metal wire earlier in the year.

The last colonist to die during the battle was Major Andrew McClary, who was hit by cannon fire from a frigate in the harbor while retreating through Charlestown neck, the narrow land bridge connecting the peninsula to the mainland.

McClary was thrown a few feet in the air by the cannon fire before landing dead, face down on the ground. Fort McClary in Kittery, Maine was later named after him.

By the end of the three-hour battle, 268 British soldiers, including a large number of officers, and 115 American soldiers, lay dead and several hundred more were wounded. About 30 American soldiers, most of whom were mortally wounded and couldn’t physically escape, were captured.

Yet another casualty of the battle was General Thomas Gage‘s military career. Gage was the commander of the British troops in Boston at the time and had ordered the assault on Breed’s Hill.

When he later called for more British troops to be sent to Boston after the battle, the British government turned against, according to the book Decisive Day: The Battle for Bunker Hill:

“The public and the government wanted a scapegoat and the first person they thought of was Gage himself. Here he was calling for more troops, implying that the government had been responsible for the failures in America; it was obvious that the man whom George III called ‘the mild general’ had to go. Three days after the news of Bunker Hill reached London the decision was made to dismiss Gage and replace him with William Howe.”

Who Won the Battle of Bunker Hill?

Although the British won the Battle of Bunker Hill, it was only a technical victory. Their heavy losses during the battle bolstered the colonist’s confidence and actually encouraged them to continue fighting the war.

The British were still trapped inside the city but were eventually forced to leave Boston the following year in March of 1776 after the Battle of Dorchester Heights.

Battle of Bunker Hill Historical Sites:

Bunker Hill Museum:

Address: 43 Monument Square, Charlestown, Mass.

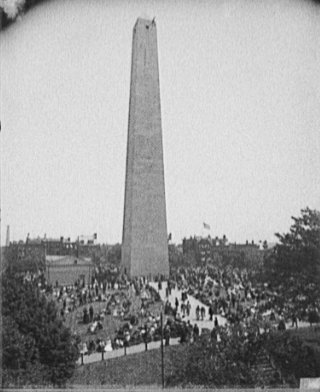

Bunker Hill Monument:

Address: Monument Square, Charlestown, Mass.

Sources:

Frothingham, Richard. Battle of Bunker Hill. Little, Brown and Company, 1890

Frothingham, Richard. History of the Siege of Boston. Little, Brown and Company, 1849

Ketchum, Richard M. Decisive Day: The Battle of Bunker Hill. Doubleday, 1962

“Bunker Hill.” The Freedom Trail Foundation, www.thefreedomtrail.org/visitor/bunker-hill.html

“The Battle of Bunker Hill.” National Parks Service, www.nps.gov/nr/twhp/wwwlps/lessons/42bunker/42facts2.htm

“Today in History June 17.” Library of Congress, memory.loc.gov/ammem/today/jun17.html

My Greatx5 Grandfather, Capt. [Lt} at that time] Benjamin Brown and two of his brothers, participated in that battle. One brother was wounded while retreating and later both brothers gave their lives for out independence.

That’s amazing I hope their in heaven so you can see them again

oh wow

Looking for an ancestor who was supposedly KIA at the Battle of Bunker Hill, looking for a William Loomis or Lummyus.

Any info would be appreciated.

William loomis fought in the battle of bunker hill and she was fighting along with George Washington. If you would like to see more. Go to history.com/williamloomis.

this website was very useful to me

Looking for any information on anyone surname of “Puffer” who fought at Bunker Hill (1775). Puffer’s originally settled in Braintree, MA. , apparently……a George Puffer was the original settler, died in Braintree in 1639. After George, there was Matthias Puffer (1635-1717), followed by Eleazer Puffer (1684-1747), followed by Lazarus Puffer (1729-1778), followed by Simeon Puffer (1759-1825), then Cornelius Puffer, who ended up re-settling in Canada (1793-1860), then John Puffer, also settling in Canada (1830-1881) and then there is a succession of Puffer’s that made Northumberland County (Ontario), Canada their home. There are still quite a Puffer’s in Braintree, MA .

It might be, the Puffer’s of that time sided with the British as many colonist did during the conflict, hence the reason family members ended up in Canada, and the French have Quebec. I’ve heard also, of American Indian & slave land grants, along with Americans leaving the Country for Canada due to the American Revolutionary war also…

this site will be helpful for my project yayaya

Looking for a surname Gunther who was KIA at Bunker Hill. He hailed from Lancaster PA. He is in our family tree and looking for information.