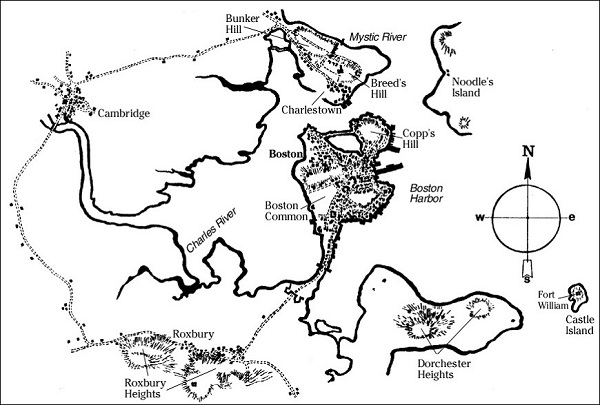

Geography greatly influenced the early battles of the Revolutionary War in Massachusetts and, in particular, around Boston.

Many of the outcomes of these early battles were a result of the local geography and the effect it had on the military strategies of the Revolutionary War.

History of Boston’s Geography:

Boston, Massachusetts looks much different today than it did a few hundred years ago. Today, it is a wide, flat city about 89 square miles in size. In 1775, Boston was a tiny, hilly peninsula about 789 acres in size.

The peninsula itself was made up of a large hill with three peaks, Mt. Vernon, Beacon Hill and Pemberton Hill, which was referred to as Trimount, and two other hills called Copp’s Hill and Fort Hill.

Boston was surrounded by several other hills in nearby Dorchester and Charlestown and was also surrounded by water on almost all sides, making it practically an island.

The only way to exit Boston on land was through a narrow land bridge, called Boston neck, in Roxbury. The surrounding countryside outside of Boston was mostly hilly and rocky and was surrounded by forests, rivers and waterways.

Boston’s geography was so distinct that the city was originally named Trimount, in honor of the three-peaked hill, and Massachusetts itself got its name from the Native-American word for the Great Blue Hill, which is an ancient volcano just outside of Boston.

Map of Boston in 1775

The following is a list of early battles around Boston where geography came into play:

The Battle of Concord:

One of the first times geography influenced a battle near Boston was during the Battle of Concord on April 19, 1775. This battle took place about 20 miles north of Boston.

General Thomas Gage sent 700 British troops, led by Lt. Colonel Smith, to Concord in search of the militia’s secret ammunition supplies stockpiled in the town.

While there, Gage ordered the troops to also take control of and guard the two bridges in town, the North bridge and the South bridge, stating to Smith: ‘You will observe by the Draught that it will be necessary to secure the two bridges as soon as possible…”

The reason was because about 100 of the 700 British soldiers in Concord were ordered to cross the Concord river via the bridges and search Colonel James Barrett’s farm, about a mile from the west bank of the Concord river.

British at Barrett farm, illustration published in Harper’s Magazine, Volume 50, 1875

The colonists at the time lived on the high ground overlooking the bridge, so if the colonists were to gain control of the bridge, the British soldiers would be cut off at the farm.

The terrain of Concord had a big impact on the events of the battle and gave the local militia an advantage over the British troops, according to the book Three to Ride: A Ride that Defied an Empire and Spawned a New Nation:

“At the corner, just passed the bridge, a side road going north to Bedford went off to the right. It was at this point, where the Concord road took a slight turn to the left, there arose a series of steep hills on the north (right) side of the road. The hills provided an excellent perch for militiamen who were streaming in to join the fight against the invaders. Lt. Col. Smith sent some of his light infantry up the hills, chasing away any militia lookouts. At Concord, the terrain was more hilly and varied than at Lexington common; with a number of hills and rivers that affected military strategy…West of the North bridge was an elevated ridge, snaking alongside the river about two hundred yards away. The elevated height of the ridge allowed a commanding view of the North bridge and surrounding road.”

Lt. Colonel Smith left less than 100 men at the North bridge to guard it while the rest of the group searched Barrett’s farm and Concord center.

Around 9am, about 400 militiamen, who had been watching the British troop’s activities from up high on the ridge, but hadn’t dared confront them yet, saw smoke rising from the town.

The smoke was actually from the British troops burning some of the supplies they found but the militia assumed the British were setting fire to the town and marched towards Concord center via the North Bridge.

It was then that they encountered the British troops at the North Bridge. The British troops quickly engaged in in a brief battle, during which the Shot Heard Round the World was fired, and they were defeated.

Three British privateers fell dead, four officers and five soldiers were wounded and the remaining soldiers abandoned the bridge and retreated back to Concord center to meet up with the rest of the British troops.

Meanwhile, the militiamen kept pouring into Concord from all of the surrounding towns. It is estimated that between 2,000 to 3,000 militiamen marched to Concord to join the fight.

Smith gathered his remaining troops at the Concord green in the center of town and around midday, realizing he was outnumbered, decided to retreat back to Boston.

The route back to Boston was surrounded by trees, boulders, ditches, ravines, small creeks and sharp bends, which the minutemen used to hide behind and fire sniper shots at the British during their retreat.

It is estimated that the British troops sustained over 200 casualties during this long march back to Boston. General Hugh Percy, who had led the First Brigade from Boston to Concord that day to rescue the Smith’s troops, later described the experience in a letter when he stated: “We retired for fifteen miles under an incessant fire, which like a moving circle surrounded us and followed us wherever we went.”

The Siege of Boston:

When the British finally got back to the Boston area, they marched to Charlestown where it took three hours to ferry the weary soldiers by boat into the city.

To prevent the British troops from carrying out anymore attacks or raids on rebel posts in the nearby countryside, the minutemen formed a blockade on Boston neck to trap the British troops in Boston.

To prevent the colonists from entering Boston and attacking the troops, the British formed their own blockade on Boston neck. This later became known as the Siege of Boston.

Due to Boston being surrounded by water on almost all sides, the British army still had access to the harbor and were still able to use their navy fleet. The rebels didn’t have a navy so they were not able to stop the British from accessing the harbor.

To prevent the British from sailing to Charlestown and escaping on foot via the land bridge there, they formed a blockade on Charlestown neck as well.

As the siege dragged on, supplies in Boston quickly dwindled while the British army awaited the arrival of supply ships from Nova Scotia. Although the colonists didn’t have a navy, American privateers were able to harass British supply ships, which caused further supply shortages and drove up food prices.

To help defend the city, General Gage fortified easily defensible positions within the city, ordering a line of cannons in Roxbury and adding cannons and artillery to four of the hills inside Boston.

The Battle of Chelsea Creek:

Cut off from the mainland, the British troops used their naval fleet to forage for supplies, particularly fresh meat and hay for the troop’s horses, on the nearby islands in and around Boston harbor.

After a skirmish on Grape Island during one of these foraging expeditions, the Massachusetts Committee of Safety decided to deprive the British troops of these supplies by removing all of the livestock and hay from these islands, which included Noddle’s island, Hog’s island, Grape island and Snake island.

On May 27 and 28 of 1775, these actions led to what is now known as the Battle of Chelsea Creek.

While carrying out these orders, the militia began burning hay on one of the islands. On May 28, spotting the smoke from the burning hay, the British ship HMS Diana headed towards the islands to investigate but became stuck in the marsh.

The militia began to attack the ship and, after the British troops were rescued by another British ship, the militia boarded the HMS Diana, stripped it of its valuables and munitions and set it on fire. This battle became the first naval battle of the Revolutionary War.

The militia returned to Noddle’s island on May 29 and May 30 to remove the remaining livestock and attempted to make the island inhabitable for the British by burning down a mansion on the island, owned by fellow patriot Henry Howell Williams, which left his family destitute.

Williams estimated that his losses totaled £3,645 and in 1787 he petitioned the Commonwealth of Massachusetts for compensation for his losses.

The Battle of Bunker Hill:

The Battle of Bunker Hill was also influenced by the geography of the region. In June of 1775, the British army was eager to break the blockade and gain control over the region again.

The First Fire from the Redoubt, illustration published in Our Country: A Household History for All Readers, circa 1877

To do so, the British planned to take control of and fortify the hills in Charlestown and Dorchester so they could then fire upon rebel posts in nearby Roxbury and Cambridge, according to the book Decisive Day: The Battle for Bunker Hill:

“[General] Howe outlined the plan in a letter written on June 12 to his brother, the admiral. First, a detachment would move out against Dorchester neck, throw up two redoubts there, and then attack the rebel post in Roxbury. Once Boston was safe from attack in that direction, Howe would take a large force to Charlestown heights and either attack the Americans in Cambridge or outflank that post, which would accomplish the same purpose. ‘I suppose the rebels will move from Cambridge,’ Howe added confidently, ‘and that we shall take and keep possession of it.’ The attack was set for June 18.’”

The colonists learned of the attack accidentally when an unidentified New Hampshire resident found out about it in a conversation with a British soldier and later relayed the details to the Committee of Safety.

To prevent the British troops from succeeding in their plan, Colonel William Prescott was ordered to march his troops to nearby Bunker hill, in Charlestown, and fortify it. When the troops arrived in Charlestown, they instead fortified Breed’s hill because Colonel Gridley and the other officers felt it was a better location for their fortifications, according to the book Battle of Bunker Hill:

“The order was explicit as to Bunker Hill; and yet a position in the pastures nearer Boston, now known as Breed’s hill, seemed better adapted to the objects of the expedition, and better suited the daring spirit of the officers.”

The reason why they fortified Breed’s Hill instead of Bunker Hill is unknown but some historians believe it was an act of defiance against the British rather than a defense strategy, according to the book Bunker Hill: A City, A Siege, A Revolution:

“Colonel Prescott’s orders told him to fortify this hill [Breed’s hill], which overlooked the roads from Cambridge to the west and from Medford to the north, as well as the waters of the Mystic river to the east. A fort built here would go a long way to stymieing a British attempt to take Charlestown to the south and then Cambridge…But instead of remaining on the grassy summit of Bunker Hill, they continued along the road to Charlestown, following a ridge that led to the smaller, seventy-five-foot-high Breed’s hill, almost half a mile to the southeast…Just a quarter mile to the south lay the wharves of Boston, with Admiral Grave’s fleet of warships anchored in the waters in between and, even more menacing, the mammoth cannons of Copp’s Hill battery pointed in their direction. To place a fort overlooking Charlestown on Breed’s Hill – right in the figurative face of the British – was an entirely different undertaking than had been ordered by the Committee of Safety. Instead of a defensive position, this was an unmistakable act of defiance. A fort built here, especially one equipped with provincial cannons that could rake British shipping and the Boston waterfront, invited a forceful response from the British army. Given the provincial’s almost nonexistent reserves of gunpowder, this was not what the Committee of Safety had in mind. But this was where Prescott, Putnam, and Gridley began to build the fort.”

Upon seeing the redoubt on the top of the hill in the morning light, the British army ordered its ships in the harbor to fire upon the fortification. The battery on Copp’s hill also fired upon the redoubt but neither caused much damage.

The British navy could have used their ships to their advantage in the battle but were reluctant to do so ever since they lost the Diana in the marsh near Chelsea Creek, according to the book Bunker Hill: A City, A Siege, A Revolution:

“Ever since the loss of the Diana, Admiral Graves had been reluctant to expose his fleet to unnecessary risk, and he had been unwilling to move any of his ships up the Mystic River. Not only could a vessel on the Mystic have provided Howe with some useful eyes and ears, her cannons could have directed a devastating stream of fire on the rear of the rebel line. Grave’s concerns about losing one of his ships in the shallows of the river did not apply to the gunboats, and Howe requested that they be rowed around the peninsula from the Charlestown milldamn to the Mystic River. The tide, however, was against them, and by the time they took up their positions on the Mystic, the battle was essentially over.”

Instead, the British army decided to wage a land battle to get Breed’s hill back and around 3pm, about 1,600 British soldiers met at the base of Breed’s hill, clad in their bright red coats, and charged at the hill through the open fields.

Because the Continental army was low on ammunition, they waited until the British were within 150 feet of the redoubt to fire. The British sustained heavy losses from this first round of fire and had to retreat back down the hill.

The British regrouped and then made a second attempt up the hill but were again thwarted by the heavy gun fire and were forced to retreat. The British waited an hour for reinforcements and then made a final attempt back up the hill just as the Continental army ran out of ammunition.

The battle was then reduced to close combat, with guns and bayonets, and the British finally took control of the bill, forcing the Americans to retreat back up the Charlestown peninsula to Cambridge.

Despite the fact that the British technically won the battle, it was still considered a victory for the colonists because the heavy losses they inflicted on the British bolstered their confidence and encouraged them to continue fighting the war.

The Battle of Dorchester Heights:

The close proximity of Boston to Fort Ticonderoga in northern New York also played an important role in the Siege of Boston. In May of 1775, the British fort was overtaken by the Green Mountain Boys and militia volunteers from Massachusetts and Connecticut, led by Ethan Allen and Benedict Arnold.

With the capture of the fort, the militia obtained a large supply of cannons and ammunition. The Continental Army was formed shortly after in June of 1775 and Washington became its leader.

In November of 1775, Washington sent Colonel Henry Knox to Ticonderoga to collect its artillery. Knox ordered the cannons to be transported to Boston on sledges during the winter of 1776. According to the book The Revolutionary War and the Military Policy of the United States, these series of actions soon lead to end of the Siege of Boston:

“Finally, however, in March – when Washington had enlisted and organized a new army, and had procured the temporary services of ten regiments of militia; when Knox had dragged the heavy cannon through the snow from Ticonderoga; when the privateers had captured an abundance of powder from the incoming British supply ships; when the fortifications were completed so as to furnish rallying-points in case of defeat – the time for taking the offensive under favorable conditions had arrived, and Washington eagerly seized the opportunity. His plan was to send Thomas with 2,000 men, supplied with intrenching tools, fascines, etc., from the Roxbury lines to seize and fortify Dorchester heights – what is now called Telegraph hill, in Thomas Park, South Boston. These heights, at an elevation of about ninety feet, commanded the channel and the south-eastern side of Boston. If occupied, with the large guns from Ticonderoga, they made Boston and its connections with the sea untenable. Howe knew this and had long contemplated an attempt to seize these hills.”

In March, the cannons finally reached Boston and were used to fortify the hills of Dorchester Heights and were aimed directly at Boston harbor and the British navy in an attempt to take control of the harbor.

Taking Cannon from Ticonderoga to Boston, illustration published in Our Country, circa 1877

When British General William Howe first saw the cannons on Dorchester Heights, he planned to retaliate by attacking the hill from the East and ordered 2,400 troops to meet at Castle Island to carry out the plan.

Washington learned of Howe’s plan and ordered 2,000 troops to reinforce the Dorchester Heights and also ordered two brigades of about 2,000 soldiers each to row across the back bay, make their way through Boston and attack the British fortifications at Boston Neck from the rear, so they could open the gates and let the Continental army in and take control of the city.

Neither plan occurred though because a storm hit Boston that afternoon and continued into the next day, forcing both sides to abandon their plans. Howe, realizing he was outnumbered and outgunned, instead decided the British could no longer hold the city and ordered the troops to evacuate.

Although they had to wait several days for favorable winds, the British troops finally left Boston on March 17, which is now known as Evacuation Day, with their fleet of ships and over 900 loyalists and sailed to Nova Scotia, finally bringing the siege and the revolutionary war in Boston, to an end.

Sources:

“List of Items Belonging to Henry Howell Williams destroyed in 1775.” Massachusetts Historical Society, masshist.org/database/1918

“North Bridge Questions.” National Park Service, nps.gov/mima/north-bridge-questions.htm

“Dorchester Heights.” National Park Service, nps.gov/bost/learn/historyculture/dohe.htm

“Battle of Chelsea Creek.” Mass.gov, Commonwealth of Massachusetts, mass.gov/eea/agencies/czm/buar/battle-of-chelsea-creek.html

/docs/Lexington%20and%20Concord%20timeline.pdf

“Battles of Lexington and Concord.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, LLC, history.com/topics/american-revolution/battles-of-lexington-and-concord

“American Revolution.” Life Magazine, 3 Jul. 1950.

Greene, Francis Vinton. The Revolutionary War and the Military Policy of the United States. Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1911.

Barnes, Ian. The Historical Atlas of the American Revolution. Routledge, 2014.

Philbrick, Nathaniel. Bunker Hill: A City, A Siege, A Revolution. Penguin Books, 2013.

Ketchum, Richard M. Decisive Day: The Battle for Bunker Hill. Pick Partner Publishing, 1962.

Redmond, John C. Three to Ride: A Ride that Defied an Empire and Spawned a New Nation. Hamilton Books, 2012.

Adnerson, Dale. Lexington and Concord, April 19, 1775. Enchanted Lion Books, 2004.

Thank you for such an informative blog.