Although the Siege of Boston lasted for almost an entire year, the British were finally forced to leave Boston, Massachusetts on March 17, 1776 during the American Revolution in Massachusetts.

The British troops were forced to leave after the continental army heavily fortified Dorchester Heights with cannons taken from Fort Ticonderoga, which resulted in the Battle of Dorchester Heights.

How Did the Siege of Boston Start?

The Siege of Boston began when British forces retreated back to Boston after the Battle of Concord, where the Shot Heard Round the World took place, on April 19, 1775.

As the British retreated back into the city, militiamen blocked off the thin land bridges to Boston and Charlestown, called Boston neck and Charlestown neck, to prevent the British troops from conducting anymore raids on the nearby countryside.

While inside the city, the British troops also reinforced the gate to the city on Boston neck to prevent the militia from entering the city and attacking them. Since the militiamen lacked a navy, the British still had control of Boston harbor.

The siege continued for 11 months and during that time all movement in and out of the city, whether it be civilian or military, was completely cut off.

To strengthen his hold over Boston, British General Thomas Gage decided to fortify some of Boston’s hills and defensible positions by placing 10 twenty-pound guns at Roxbury Neck and also fortified four of the nearby hills. In doing so, Gage also decided to abandon Charlestown and Dorchester Heights, which is a decision he would later regret.

Map of Boston and Dorchester Heights in 1776

A number of significant battles took place during the siege, such as the Battle of Bunker Hill, during which Gage took back Charlestown, but as time went on and winter approached, the British began making plans to abandon Boston and move their base of operations to New York so they could work out a better plan to squash the rebellion, according to the book The Howe Brothers and the American Revolution:

“Between April and December 1775 the ministry and its general officers worked out a plan for ending the rebellion in a single campaign. They decided to strike hardest at New England, at the very center of resistance. Considering the countryside too difficult and the colonists too hostile to permit a regular campaign from Boston, they intended to strangle rather than conquer New England. The main British army would abandon Boston for New York as soon as possible. It would then occupy the Hudson River Valley while detachments captured Rhode Island and scoured the coast from New York to Maine. By the end of the campaign, troops advancing up the Hudson would join with an army from Canada to complete the encirclement of New England and to attack the frontier of Massachusetts.”

Problems arose due to delayed communication and a lack of adequate transport to carry the large number of British troops in Boston to New York and, as a result, their plans to leave Boston were delayed.

Due to this delay, the British troops were forced to wait out the winter until Spring arrived, according to the book 1776 by David McCullough:

“Such were the delays in communication across the ocean that by the time General Howe received orders from London to ‘abandon Boston before winter’ and ‘remove the troops to New York,’ it was too late – winter had arrived. Besides, there were too few ships at hand to transport the army and the hundreds of loyalists about whom Howe was greatly concerned, knowing what their fate could be if they were left behind. Seeing no reasonable alternative, Howe would wait for spring when he could depart at a time and under conditions of his own choosing. He expected no trouble from the Americans. ‘We are not under the least apprehension of an attack on this place from the rebels by surprise or otherwise,’ he assured his superiors in London and further stressed the point at a meeting with his general staff on December 3. Should, however, the rebels make a move on Dorchester, then, Howe affirmed, ‘We must go at it with our whole force.’”

How Did the Siege of Boston End?

By the fall, the rebels were frustrated that the Siege of Boston had become a stalemate. They felt they had to make a bold move or the siege would continue to drag on.

The rebels decided to use the geography of the area to their advantage. They knew that if they made a move on Dorchester Heights, the British would either attack it or flee.

Dorchester Heights was one of the many hills that surrounded Boston and it had a commanding view of the harbor where the British navy kept their fleet. If the rebels could get control of the hill with heavy artillery or cannons, the British would see it as a threat to their troops and respond accordingly.

In November, Henry Knox suggested to George Washington that they drag 59 cannons, captured at Fort Ticonderoga the previous spring, over 300 miles to Boston to bolster its defenses and drive the British out.

Washington agreed and sent Knox to Fort Ticonderoga to oversee the expedition. Knox arranged for the cannons to be dragged from the fort to Boston on heavy sleds over the snow and ice. After 56 days, the cannons finally arrived outside Boston on January 25, 1776.

Washington had to wait for an order of gunpowder to arrive though to actually fire the cannons. When the gunpowder did arrive, Washington placed some of the cannons at Lechmere’s Point and Cobble Hill in Cambridge as well as at Lamb’s Dam in Roxbury.

To create a diversion while hay bales were placed on Dorchester Heights to hide the activity on the hill, Washington ordered the cannons on the other hills to fire on the town on the night of March 2, which the British responded to by returning fire. In a letter to John Adams, dated March 2, 1776, Abigail Adams described the roar of the cannon fire in Boston that night:

“But hark! The house this instant shakes with the roar of cannon…I have been to the door and find ’tis a cannonade from our army. Orders I find are come for all the remaining militia to repair to the lines a Monday night by 12 o’clock. No sleep for me tonight…I went to bed after 12 but got no rest. The cannon continued firing and my heart beat pace with them all night.”

The same process was repeated the following night, with no casualties on either side on either night.

On March 4, the cannon fire started up again while 2,000 soldiers marched to Dorchester Heights and began building trenches and cannon placements. To encourage his men while they worked, Washington reminded them that the next day was March 5, which was the anniversary of the Boston Massacre.

Early in the morning, a relief force of 3,000 soldiers showed up as well as an additional five regiments of riflemen who took up positions along the shore. By dawn, everything was ready and 20 cannons, aimed directly at the British fleet in Boston harbor, were in place on the 110-foot-high hill.

The Battle of Dorchester Heights:

At daybreak, the British were amazed by what they saw on the hill, according to the book 1776 by David McCullough:

“It was an an utterly phenomenal achievement. General Heath was hardly exaggerating when he wrote, ‘Perhaps there was never so much work done in so short a space of time.’ At daybreak, the British commanders looking up at the Heights could scarcely believe their eyes. The hoped-for, all-important surprise was total. General Howe was said to have exclaimed, ‘My God, these fellows have done more work in one night than I could make my army do in three months.’ The British engineering officer, Archibald Robertson, calculated that to have carried everything into place as the rebels had – ‘a most astonishing night’s work’ – must have required at least 15,000 to 20,000 men.”

General Howe called a council of war and decided that his fleet of ships in the harbor was in immediate danger and that the honor or reputation of the British military was at stake. With that in mind, he ordered 2,400 troops to meet at Castle Island and then storm Dorchester Heights.

When Washington learned Howe planned to attack Dorchester Heights, he ordered 2,000 troops to reinforce the hill. He also ordered two brigades, made up of about 2,000 soldiers each, to row across the back bay, march through Boston and attack the British fortifications at Boston Neck from the rear. The plan was to defeat the soldiers at the gates and then open the gates to let the Continental army in to take control of the city.

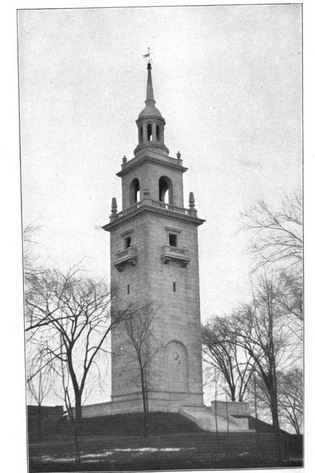

Dorchester Heights Monument circa 1902

None of these plans happened though because a storm struck Boston that afternoon and continued into the next day, forcing both sides to temporarily abandon the attack.

After the storm finally ended, Howe had reconsidered his plan and decided that his army’s resources would be better spent elsewhere. On March 8, Howe sent the following message to General Washington:

“As his excellency General Howe is determined to leave the town, with the troops under his command, a number of the respectable inhabitants, being very anxious for its preservation and safety, have applied to General Robertson for his purpose, who, at their request, has communicated the same to his excellency General Howe, who has assured him that he has no intention of destroying the town, unless the troops under his command are molested during their embarkation, or at their departure, by the armed force without; which declaration he gave General Robertson leave to communicate to the inhabitants. If such an opposition should take place, we have the greatest reason to expect the town will be exposed to entire destruction…”

The message was not given a formal reply but was accepted. Chaos immediately engulfed Boston as hasty plans were made for the troops to evacuate the city. The rebels watched from the neighboring hills as troops worked day and night carrying artillery, cannons and supplies to their ships.

Howe issued a proclamation ordering all inhabitants of the town to hand over their linens and woolen goods and threatened that if they didn’t, they would be treated as a rebel.

Howe later issued another order that basically called for the town to be looted of particular goods, such as weapons, furniture, sugar, salt and flour, because the goods “in the possession of the rebels, would enable them to carry on war.”

Stores and homes were broken into and stripped of their goods. Whatever couldn’t fit on the ships was thrown into the harbor, including the British commander’s stagecoach, cannons, wagons, wheelbarrows, smashed up furniture and supplies like salt, flour and sugar.

A brief skirmish happened on the night of March 9, when Washington sent some troops to build a battery on Nook’s hill, with the intention to use it to harass British shipping vessels.

The men working on the battery kindled a small camp fire which accidentally alerted the British to their location and caused them to open fire on the hill. The bombardment continued all night and five men were killed.

Although plans were underway to leave the city, the British had to wait for favorable winds. Finally, the British army withdrew from Boston on March 17, which is now known as Evacuation Day, with their fleet of ships and over 1000 loyalists and sailed to Halifax, Nova Scotia, according to the book 1776 by David McCullough:

“It was a spectacle such as could only have been imagined until that morning. There were 120 ships departing with more than 11,000 people packed on board, – 8,906 King’s troops, 667 women and 553 children, and in addition, waiting down the harbor, were 1,100 loyalists. ‘In the course of the afternoon,’ wrote James Thatcher, ‘we enjoyed the unspeakable satisfaction of beholding their whole fleet under sail, wafting from our shores the dreadful scourge of war.’ People on shore were cheering, weeping. ‘Surely it is the Lord’s doings and it is marvelous in our eyes,’ wrote Abigail Adams. But then the whole fleet came to anchor at King’s road and with the arrival of General Howe’s flagship, Chatham, every ship-of-war fired a roaring 21-gun salute, and the full 50 guns of the Chatham answered in kind – an ear-splitting reminder of royal might.”

In 1898, city officials built a Georgian white marble revival tower on Dorchester Heights to commemorate the battle that led to then end of the Siege of Boston.

Sources:

Frothingham, Richard. History of the Siege of Boston, and of the Battles of Lexington, Concord, and Bunker Hill. Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1849.

French, Allen. The Siege of Boston. The Macmillan Company, 1911.

Gruber, Ira D. The Howe Brothers and the American Revolution. University of North Carolina Press, 2014.

McCullough, David. 1776. Simon & Schuster, Inc, 2005.

“Dragging Cannon from Fort Ticonderoga to Boston, 1775” The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, www.gilderlehrman.org/history-by-era/war-for-independence/resources/dragging-cannon-from-fort-ticonderoga-boston-1775

“Henry Knox Diary, 20 November 1775 – 13 January 1776.” Massachusetts Historical Society, www.masshist.org/database/viewer.php?item_id=463&pid=15