General Thomas Gage was the Commander-In-Chief of North America for the British army in the Revolutionary War.

As the military governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay, in April of 1775, Gage and his troops inadvertently started the Revolutionary War when they attempted to arrest Samuel Adams and John Hancock and seize the colonist’s ammunition supplies in the countryside surrounding Boston.

These actions led to the famous battles of Lexington and Concord and the Siege of Boston, which ushered Britain into the eight-year long war with colonists that eventually ended with Britain’s defeat in 1783.

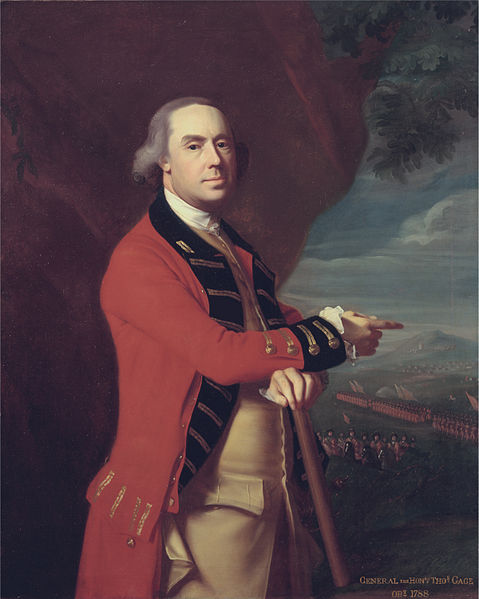

General Thomas Gage, oil painting by John Singleton Copley circa 1788

According to the book Paul Revere’s Ride, which discusses many key players in the American Revolution, failure was familiar to Gage since he descended from a long line of men who supported Britain’s many lost causes over the years:

“As early as 1215, several Sussex Gages were said to have backed King John against Magna Carta. When the Reformation came to England they sided with the Catholic party, and one of them became the jailor of the Protestant Princess Elizabeth, England’s future Queen. During the English Civil War, the Gages rallied to the Royalist cause of Charles I and suffered a heavy defeat. In the Glorious Revolution of 1688, they stood with James II and were defeated yet again. When the house of Hanover inherited the throne the Gages became Jacobites, stubbornly faithful to the hopeless cause of a Catholic King over the water.”

Unlike his predecessors, Gage did at least experience triumph momentarily when his troops won a minor victory in the Battle of Bunker Hill.

Yet, although the British technically won that battle, they suffered heavy losses at the hands of the colonists, which only encouraged the rebellion and boosted the colonist’s morale, as British General Clinton noted in his diary that day, “A few more such victories would have shortly put an end to British dominion in America.”

Fortunately, Gage did not have to watch Britain lose the war first hand since the British government had lost confidence in his military abilities and replaced him with General William Howe immediately after the Battle of Bunker Hill. Gage left Boston on October 10 on a ship bound for England.

Gage returned to England amid heavy criticism from his colleagues, and died a little over a decade later.

Sources:

“Battle of Bunker Hill.” Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/teachers/lyrical/poems/bunker_hill.html

Brooks, Victor and Robert Hohwald. How America Fought Its Wars: Military Strategy from the American Revolution to the Civil War. De Capo Press, 1999

Fischer, David Hackett. Paul Revere’s Ride. Oxford University Press, 1995

I am a direct decendant of General Gage and would like to write a historical novel on Maragret, his wife. I would like to start with her family, Van Cortdlands. Do you have any suggestions as to start?

Vaun

Salem had many supporters of General Gage. The attached post is about Henry and Weld Gardner (brothers). We will be looking further into this side of the ordeal.

Robert Gray of Stanford while looking at houses owned by William “Old Billy” Gray mentions one built by Hon. William Browne, Esq. It was there that Browne feasted Gage while the Salem patriots met. The General missed a chance as Salem could have been the first of the conflicts that ensued later.

Billy Gray had been an apprentice to Samuel Gardner, ancestor of Henry and Weld.

That’s an awesome idea. I’d love to read that when it is published. I don’t really have any suggestions but I think it sounds very promising.

It is true that Howe had not replaced Gage before the Battle of Bunker Hill, but the battle plan was Howe’s, not Gage’s. Are you certain that Gage was on the field during the battle? I’ve never read that. I know that Howe was. Gage was resentful that Howe, Henry Clinton, and John Burgoyne were being sent to Boston and that the king had place impossible demands on him. Here is an excerpt on this subject matter from my historical novel, “Crossing the River.”

What the King had demanded had proved impossible to enforce.

Refusing to violate constitutional law, eschewing heavy-handed repression, implementing, instead, a benign, yet firm, consistent policy, Gage had attempted to win the obedience of the populace. His attempts to do what was lawful and just had been thwarted at virtually every turn.

He had been unable to stop the town meetings in Salem and Boston. He had nominated royal judges to the Massachusetts bench. Loyalist juries had refused to serve. Many judges, fearful of reprisal, had refused to sit. Seven months ago he had removed 250 half-barrels of powder from the Provincial Powder House at Charlestown and, additionally, several cannon at Cambridge. The powder had been the lawful property of the Province of Massachusetts, not the illegal Provincial Congress and the proliferating town militias. The following day 4,000 provincials, incited by fraudulent rumors, had demonstrated on the Cambridge Common! Dubbed the “Powder Alarm,” the uprising had instructed him to proceed thereafter with greater circumspection.

Subsequently, he had fortified the Neck; entrance and egress were now carefully monitored. He had ordered the inhabitants of Boston to surrender their weapons, after having purchased the inventory of every gun merchant. He had advised Lord Dartmouth in London that there was “no prospect of putting the late acts in force, but by first making a conquest of the New England provinces.” That would necessitate a force of at least 20,000 soldiers. In November he had urged that the Coercive Acts be suspended until more troops were provided. Waiting for Dartmouth’s response, in December he had planned the removal of Provincial gunpowder and cannon from a crumbling fortress near the entrance of Portsmouth Harbor. The mechanic Paul Revere had alerted the local militia before Admiral Graves and a detachment of British soldiers had embarked on the sloop H.M.S. Canceaux. Four hundred militiamen had overwhelmed the guard of six, injuring its captain. A regular had been struck on the head with a pistol. One hundred barrels of gunpowder and sixteen cannon had been carried away. Shortly thereafter, militia companies had seized munitions at royal forts in Newport and Providence.

Two months ago he had attempted to remove from a Salem forge eight new brass cannon and field pieces converted from the cannon of four derelict ships. Despite the care he had taken to keep the operation a secret, word had reached the town of Salem before the seaward arrival of Colonel Leslie’s regulars. Thwarted by a raised drawbridge that provided access to the forge, Leslie, to avert bloodshed, had acquiesced. Despite his efforts to act humanely, to respect the constitutional rights of the populace, to restrain his soldiers’ desire to respond aggressively to invidious criticism, Boston’s citizenry perceived their governor/commanding general to be a tyrant.

From the Earl of Dartmouth’s most recent letter, dated January 27, which he had just received, Gage had learned that the King had angrily rejected his requests. Troops were, in fact, on the way: 700 Marines and three regiments of foot. But, the King and his ministers did not accept Gage’s estimate that 20,000 soldiers were needed to quell the rebellion. If General Gage sincerely believed that more soldiers were required than what he was being provided, he should recruit men from “friends of the government in New England.” Dartmouth had stated succinctly Gage’s duty. “The King’s dignity, and the honor and safety of the Empire, require, that, in such a situation, force should be repelled with force.” Seize the ringleaders; disarm the populace. They are “a rude Rabble without plan, without concert, and without conduct. A smaller force now, if put to the test, would be able to encounter them with greater probability of success than might be expected from a great army.”

He was bitter. He had three good reasons to be. The “rude Rabble” had rejected with prejudice his benign governance. His superiors were demanding outcomes that no governor or general or he could realistically accomplish. If men in Government like Sandwich, Townshend, Rigby, and Germain continued to have their way, despite what he might yet practically achieve, he would be relieved of his command.

Hi Harold, thanks for your comment. You are correct, Gage didn’t fight in the battle but he did command the troops and gave the official order to attack.

Hi, Rebecca. That was my understanding as well.

Yorktown, ultimately, appears to have been intentionally lost, so I believe there might be some truth to this thing of failure as personally less significant. In reference to Concord, I have always been of the impression that the intent was not to seize gunpowder but to retrieve cannon that men of Gloucester had stolen; the British never did find those cannon.