The Charles River is an 83-mile-long river in Massachusetts that flows northeast from Hopkington to Boston Harbor. The river follows a meandering, winding course which is the result of the rocky terrain of the area.

The Charles River starts at Echo Lake in Hopkington, which is a man made lake created by the Milford Water Company in 1881 to provide a reservoir for nearby communities.

The following is a history of the Charles River:

The Charles River was formed towards the end of the Pleistocene epoch, the Ice Age, which occurred about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago.

At the beginning of the Ice Age, the Charles River did not exist and the greater Boston area was instead covered by a series of streams and rivers (Clapp 255.)

The region west of Medway had two main streams that flowed south to the Blackstone River in Rhode Island. The Populatic River also flowed south to the Blackstone River and the Baggistere River flowed North to the Neponset River.

The Merrimack River flowed southeast from Lowell to Boston Bay while the area north of Dedham and east of Needham had an independent stream and the area in the Sudbury and Assabet basins were early tributaries of the Charles.

Some of these rivers and streams, such as the Merrimack and the Milford and Medway branches of the Blackstone, maintained their original courses until the Pleistocene epoch when the landscape dramatically changed.

When the Pleistocene epoch began, the land became elevated due to a mantle of boulder clay being spread over the surface of the land.

This was caused by glaciers moving across the region, carrying sand, rocks and other sediments with it, which changed the topography of the land by creating new drumlins and filling in existing gorges and valleys.

At the close of the Pleistocene epoch, the glaciers began to retreat and melt which released large volumes of water and the glacial lakes in the area began to drain as new valleys and passes were opened up and new streams and drainage systems formed over the recently uncovered land. As a result, the Charles River began to form.

This newly formed river followed the course of the lowest outlets but encountered various new obstacles along the way, particularly several ancient preglacial valleys blocked or filled in by sand, which forced the river to meander to find a way around them and thus created a winding, meandering course.

As the glaciers retreated, paleoindians began entering the New England region about 12,000 years ago and Native Americans began inhabiting the watershed of the Charles River from 4000 B.C (6,000 years ago) to around 1617 A.D.

During this time, the Native American tribe who lived in the area, the Massachusett, named the river Quinobequin, which means “meandering.”

When French explorers Sieur de Monts and Samuel Champlain explored the area in 1605, they described the river as “a very broad river, which we named River du Guast” according to Champlain’s first hand account of his travels titled The Voyages of Samuel Champlain.

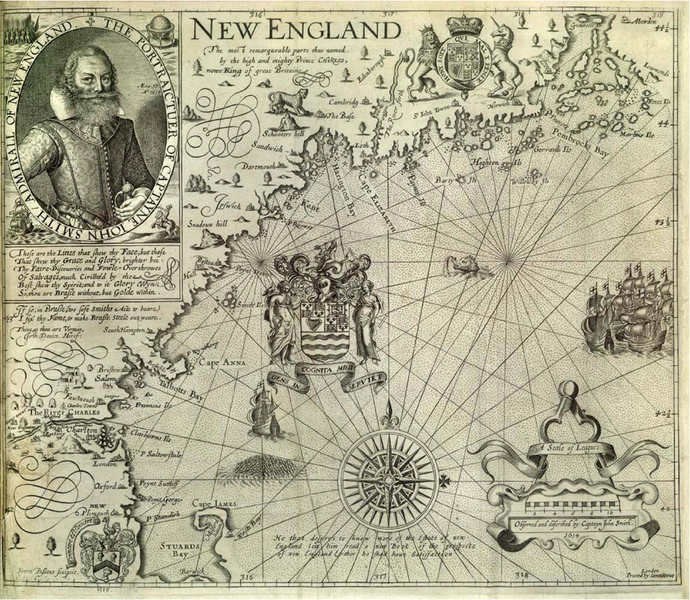

In the spring of 1614, English explorer John Smith explored and mapped New England and named many of the geological features of the region on his map.

It is said that Captain John Smith originally named the Charles River the Massachusetts River, after the local tribe, but when he returned to England in the summer of 1614, he presented the map to Prince Charles and was encouraged to change the indigenous names to English names and named the river after the prince instead.

In 1630, the Massachusetts Bay Colony was established in Boston along the Charles River and, two years later, the General Court for the Massachusetts Bay Colony authorized the construction of a weir on the Charles River at the fall line in Watertown.

In 1634, a grist mill dam was built on the Charles River at Watertown which changed the flow of river, captured sediments and limited fish migration and, in 1643, another dam and mill were constructed along the river on Causeway Street in Boston.

In 1799, Mount Vernon, one of the many hills that once made up Boston, was cut down and the soil was used to fill in the marshland to make Charles Street which greatly reduced the natural filtration system for the river.

New public water supply projects in 1840 carried waste directly to the Charles River via street drains and sewers. The bacteria load of the river increased dramatically and the waste on the mudflats caused a stench.

Between 1855 and the 1880s, the remaining hills in Boston were cut down and used to fill in the Back Bay in an effort to reduce the stench from the mudflats and expand the available land in Boston.

In 1878, the first metropolitan sewer was constructed in Boston which created concern about the lowered groundwater table.

These growing concerns about the river prompted Boston to adopt Frederick Law Olmsted’s Sanitary Improvement of the Back Bay plan in 1879 which created the Fens, a restored salt marsh in the Back Bay used to absorb flood waters and sewage discharge.

In 1881, the Milford Water Company built a dam at the source of the Charles River in Hopkington, at a site where three streams and an underground spring converge into one, to create a reservoir called Echo Lake.

The water from the reservoir was piped through an opening in the Milford Dam where it passed through a series of filters, making it one of the cleanest sections of the Charles River. The river then emerged near the Dilla Street Bridge in Milford to continue its course.

In 1884, all of the Back Bay, except for a portion of the entrance of Stony Brook and Muddy River, was filled in. The reduced river area and marshes combined with sewage load caused public health concerns.

In 1908, a dam was constructed between Boston and East Cambridge to create a settling basin for sediments in the water but it resulted in heavily contaminated bottom sediment, an anoxic zone created by salt water intrusion from the harbor, it eliminated the tidal flushing in the river and made Olmsted’s “fens solution” unworkable.

By the 1960s, the Charles River had become infamous for being dirty and polluted. As a result, the Charles River Watershed Association was founded in 1965 to help clean up the river. Ironically, in November of that same year, the rock group The Standells released their hit song Dirty Water, which was an ode to Boston and the Charles River.

In 1978, a new dam was constructed at the mouth of the harbor to control flooding.

In 1988, the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority created the combined sewer overflow program (CSO) as a result of an EPA/CLF Boston Harbor Cleanup lawsuit.

Things started to change for the river in 1995 when the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) launched the Clean Charles Initiative to make the Charles River fishable and swimmable and ordered municipalities to eliminate illicit discharges in city storm drains.

That year, the EPA began assigning a report card grade for the lower Charles each calendar year and assigned the river a D grade on its first report card.

The new grading criteria was:

A – meets swimming and boating standards nearly all of the time

B – meets swimming and boating standards most of the time

C – meets swimming standards some of the time & boating standards most of the time

D – meets swimming and boating standards some of the time

F – fails swimming and boating standards most of the time

Over time, the river slowly began to improve and the EPA gave the Charles River a C- grade in 1996.

In 1997, the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority’s Long Term CSO Plan was approved which required closure of seven combined sewer overflows and reduction of discharges to 162 million gallons per yer.

In 1999, the EPA assigned the Charles River a B- grade for the first time.

In 2000, the Charles River Conservancy was founded and the Deer Island Sewage Treatment Plant and outfall tunnel was completed which reduced combined sewage overflows to the Charles River and improved the water quality in Boston Harbor.

The condition of the river continued to improve and the EPA gave the Charles River a B grade in 2000.

In 2004, Waltham, Watertown, Newton and Brookline were required to reduce illicit discharges into the river and the EPA gave the Charles River a B+ grade.

In 2005, the Charles River Swimming Club was founded. In May, the EPA gave the Charles River a B+ grade.

The separation of Stony Brook, a tributary stream that was the largest source of bacteria to the lower Charles, was complete in 2006 and the EPA gave the Charles River a B++ grade the following year.

In 2013, the Brookline sewer separation project was completed which lowered the combined sewer overflow discharges to the river. The Charles River received an A- grade for the first time that year.

In 2014, the Charles River’s grade slipped to a B+ grade but, in 2017, the river received an A- grade again.

Starting in 2019, the Charles River Watershed Association, in coordination with the EPA, began using a new assessment method and began grading for six waterbody segments:

The Upper Watershed (Hopkinton to Medfield)

The Upper Middle Watershed (Sherborn to Dedham)

The Lower Middle Watershed (Newton to Waltham)

The Lower Basin (Watertown to Boston)

The Stop River

The Muddy River

In 2019, the Upper Watershed and the Stop River received A- grades, the Upper and Lower Middle Watershed received A grades, the Lower Watershed received a B grade and the Muddy River received a D- grade.

In 2021, the Upper Watershed and the Stop River received B+ grades, the Upper and Lower Middle Watersheds received A grades, the Lower Basin received a B- grade and the Muddy River received a C- grade.

In 2022, the Charles River Watershed Association filed a federal lawsuit against the EPA, claiming that the EPA failed to deliver on its plans to help protect the river by not issuing permits aimed at reducing storm water pollution into the Charles River which contributed to toxic algae blooms.

Sources:

Clapp, Frederick. Geological History of the Charles River. University of Michigan, 1901.

Norton, Michael P. “Lawsuit Alleges EPA Failing to Protect Major Rivers.” WBUR, 3 Nov. 2022, wbur.org/news/2022/11/03/massachusetts-rivers-stormwater-runoff-lawsuit

Fiorentino, Anna and Lia Petronio. “You love that dirty water. But how dirty is it really?” Charles River Conservancy, 30 Aug. 2018, thecharles.org/uncategorized/you-love-that-dirty-water-but-how-dirty-is-it-really/

“History of Human Impacts on Charles River.” EPA.gov, epa.gov/charlesriver/history-human-impacts-charles-river

“The Charles River Initiative.” EPA.gov, epa.gov/charlesriver/charles-river-initiative

“About the Charles River.” EPA.gov, epa.gov/charlesriver/about-charles-river

“Back Bay Fens.” The Cultural Landscape Foundation, tclf.org/landscapes/back-bay-fens

“Where It All Begins.” Charles River Watershed Association, charlesriverwatershed.blogspot.com/2012/11/where-it-all-begins.html

Hv, Vivek. “Charles.” Science in the News, Harvard University, sitn.hms.harvard.edu/flash/2019/charles/

“History of the Charles River.” Explore the Charles, explorethecharles.com/history-of-the-charles-river/