Deborah Sampson was a woman who disguised herself as a man and fought as a soldier in the Continental Army during the American Revolution.

She was one of only a small number of women who fought in the Revolutionary War and was later awarded a pension for her military service.

The following are some facts about Deborah Sampson:

Deborah Sampson’s Childhood & Early Life:

Deborah Sampson was born on December 17, 1760 in Plympton, Massachusetts to Johnathan Sampson, Jr. and Deborah Bradford.

Bradford was a direct descendant of the Mayflower pilgrim, William Bradford, and Johnathan Sampson, Jr., was a direct descendant of the Mayflower pilgrims Miles Standish as well as John Alden.

Deborah Sampson was the oldest of seven children. The Sampson family lived in poverty due to Johnathan Sampson, Jr’s, bad luck and lack of business skills.

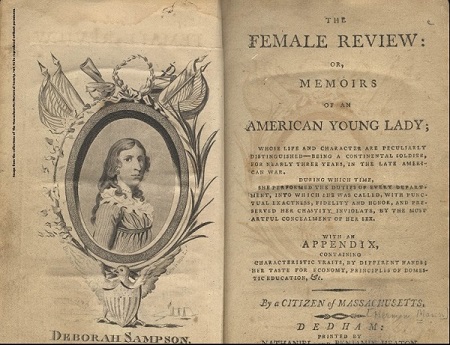

According to Sampson’s biographer, Herman Mann, who personally interviewed Sampson for his biography on her titled The Female Review, or the Memoirs of an American Young Lady, after Sampson’s grandfather died in 1758, her father Johnathan was cheated out of his inheritance by his brother-in-law, which eventually led him to go to sea to seek his fortune:

“He [Johnathan Sampson, Jr.] met with a sad disappointment in his father’s estate, occasioned by the ill designs, connivings and infinuations of a brother-in-law. Thus, he was disinherited of a large portion that belonged to him by hereditary right. This circumstance, alone, made such impressions on his mind, that, instead of being fired with a just spirit of resentment and emulation, to supply, by good application and economy, that of which he had been unjustly deprived, he was led into opposite pursuits, which she [Deborah Sampson] laments, as being his greatest misfortune. Such was her father’s local situation after his marriage with her mother. She informs, that she had but very little knowledge of her father during her juvenile years. Despairing of accumulating an interest by his domestic employments, his bent of mind led him to follow the sea-faring business, which, as her mother informed her, he commenced before her birth. However great his prospects were, that fortune would prove more propitious to his prosperity and happiness upon the ocean, than it had done on the land, he was effectually disappointed: – For after he had continued this fruitless employment some years, he took a voyage to some parts of Europe, from whence he was not heard of some years. At length, her mother was informed, he had perished in a ship-wreck.”

Deborah Sampson, illustration published in the Female Review, circa 1797

Recent evidence suggests that Sampson’s father did not died at sea but had instead abandoned his family and moved to Lincoln County, Maine where he acquired a common law wife named Martha and had two more children. He continued to live in poverty there until he died in 1811 and was buried in a paupers lot in Fayette cemetery.

Unable to provide for her children with her husband gone, Sampson’s mother had to place her children in the homes of various relatives and friends.

At the age of ten, Deborah Sampson was then hired out as an indentured servant to the family of Jeremiah and Susannah Thomas.

Jeremiah Thomas was a patriot who heavily influenced Sampson’s political opinions and education, according to the book The History of the Town of Middleboro, Massachusetts:

“Mr. Thomas, as an earnest patriot, did much towards shaping the political opinions of the young woman in his charge, who early developed talent and a strong desire for knowledge. Her perceptions were quick and her imagination lively; she soon became absorbed in the stirring questions of the day.”

After she was released from indentured servitude at the age of 18, she worked as a local school teacher during summer sessions in 1779 and 1780 in Middleboro.

Deborah Sampson in the Revolutionary War:

In the winter of 1781, Sampson began feeling restless and wanted to travel and explore other pursuits. Knowing that her options as a young woman were limited, she came up with the idea of cross-dressing as a man and sought out the advice of a fortune-teller to get some insight into her future, according to her biography The Female Review:

“Whilst she was deliberating on these matters, she privately dressed herself in a handsome suit of man’s apparel and repaired to a prognosticator [fortune-teller]. This, she declares, was not to stimulate, but to divert her inclinations from objects which not only seemed presumptuous, but impracticable. She informed him she had not come with an intention to put entire confidence in his delusory suggestions; but it was partly out of principle, but mostly out of curiosity. He considered her as a blithe and honest young gentleman. She heard his preamble. And it was either art or accident, that he told her, pretty justly, her feelings – that she had propensities for uncommon enterprises, and pressed to know why she had held them in suspension for so long. Having predicated that the success of her adventures, if undertaken, would more than compensate a few difficulties, she left him with a mind more discomposed than when she found him. But before she reached home she found her resolution strengthened. She resolved soon to commence her ramble, and in the same clandestine plight, in which she had been to the necromancer. She thought of bending her first course to Philadelphia, the metropolis of America.”

Sampson’s departure was delayed due to lingering winter weather so, as she waited for spring to arrive, she sewed herself a man’s coat, waistcoat and breeches using the Thomas family’s sewing patterns and purchased a pair of men’s shoes, hat and etc.

It was during this time that Sampson got the idea to instead join the military as a male soldier, according to The Female Review:

“Before she had accomplished her apparatus, her mind being intent, as the reader must imagine, on the use to which they were soon to be appropriated, an idea no less singular and surprising than true and important, determined her to relinquish her plan of travelling for that of joining the American Army in the character of a voluntary soldier. This proposal concurred with her inclinations on many accounts. Whilst she should have equal opportunities for surveying and contemplating the world. She should be accumulating some lucrative profit; and in the end, perhaps, be instrumental in the cause of liberty, which had for nearly six years enveloped the minds of her countrymen.”

There is a lot of confusion about when Deborah Sampson actually enlisted in the army. Several sources, including her biography, state that she enlisted in the 1781 while others state it was 1782, according to an article in the Westchester Historian journal:

“Did Deborah become a soldier in 1781 or 1782? This is the question which has puzzled anyone trying to write about her. In petitioning for back pay and for various pensions, Deborah, in different documents, used both dates. Most people have concluded that the 1782 date is correct; using that date, however, creates many problems that have not been satisfactorily resolved by others. Some things in Mann’s narrative do not check out, although many things in it appear to be true. The people mentioned existed and can be placed where Deborah said, even when at first her statements may not appear logical. Mann’s version of Deborah’s story is the only one that hangs together as a whole. The year of Deborah enlistment may never be conclusively resolved, but there is much in Mann’s manuscript to support the claim for 1781.”

According to her biography, The Female Review, Sampson disguised herself in the coat, waistcoat and breeches she sewed, and traveled to Worcester, Mass in April of 1781, where she enlisted in Captain Webb’s company in the 4th Massachusetts Regiment, under the alias Robert Shurtliff.

The war had already moved on to the New York area by the time Sampson enlisted and she was sent to fight as a light infantryman in the Hudson Valley. According to The Female Review, Sampson found war to be exhausting and terrifying:

“She says she underwent more with fatigue and heat of the day, than by fear of being killed; although her left-hand man was shot dead at the second fire, and her ears and eyes were continually tormented with the expiring agonies and horrid scenes of many others struggling in their blood. She recollects but three on her side who were killed, John Bebby, James Battles and Noble Stern. She escaped with two shots through her coat, and one through her cap…She now says no pen can describe her feelings experienced in the commencement of an engagement, the sole object of which is to open the sluices of human blood. The unfeigned tears of humanity has more than once started into her eyes in the rehearsal of such as scene as I have just described.”

While fighting in New York, Sampson was wounded in battle. Mann states in The Female Review that she was shot in the thigh during a skirmish with Tory soldiers, but according to her pension application in 1818, Sampson said she received the wound at the Battle of Tarrytown in July of 1781.

After removing the bullet herself, the wound never healed properly and caused her pain and discomfort for the rest of her life. She was wounded again four months later when she was shot through her shoulder.

Although Sampson survived her wounds, she eventually came down with a fever shortly after being dispatched to fight in Pennsylvania and was hospitalized in the summer of 1783.

It was then that the doctor attending to her, Dr. Barnabas Binney, removed her clothes to treat her and discovered the cloth binding her breasts. Binney didn’t immediately report her and instead let her recover in peace at his own home with his wife and family.

In September, after Sampson had fully recovered, Binney asked her to deliver a personal letter to General Patterson. Upon delivering it, Patterson informed her that the letter said she was a woman in disguise.

Realizing her secret was out, Sampson admitted she was a woman and asked to be spared punishment for her dishonesty. Patterson was surprisingly supportive and instead said she should be rewarded for her service, according to the Female Review:

“He told her, she might not only think herself safe, while under his protection, but that her unrivalled achievements deserved ample compensation – that he would quickly obtain her discharge, and she should be safely conducted to her friends.”

Sampson was given an honorable discharge in October of 1783 and returned home to Massachusetts.

Deborah Sampson After the Revolutionary War:

After her discharge, Sampson married Benjamin Gannett on April 7, 1785. The couple had three children, Earl, Mary and Patience and adopted an orphan named Susanna Baker Shepard. The family ran a small farm in Sharon, Massachusetts but were not very successful at it and lived in mild poverty.

Like many soldiers of the revolution, Sampson had difficulty trying to obtain a pension. After she campaigned unsuccessfully to secure a pension in 1790, she became discouraged and feared Congress would never award her any money for her role in the war.

Although Sampson had kept a journal of her experiences during the war, it was lost in October of 1783 after a boat she was traveling on while returning from Pennsylvania capsized during a storm.

Years later, in 1797, Sampson met Herman Mann who worked with her to publish her biography The Female Review.

Following the publication of the book, Sampson embarked on a public speaking tour throughout eastern New York and New England. During her performances, she dressed in her male uniform and performed maneuvers from the manual of arms.

Statue of Deborah Sampson at the Sharon Library, Sharon, Mass

With the success of her biography and speaking tour, Sampson renewed her campaign for a pension and gained the support of Paul Revere, who visited her farm in 1804 and wrote the following letter to Congressman William Eustis on February 20, 1804:

“Sir, Mrs. Deborah Gannett of Sharon informs me, that she has inclosed to your care a petition to Congress in favour of her. My works for manufacturing of copper, being a Canton, but a short distance from the neighbourhood where she lives; I have been induced to enquire her situation, and character, since she quitted the male habit, and soldiers uniform; for the more decent apparel of her own sex; & since she has been married and become a mother. Humanity, & justice obliges me to say, that every person with whom I have conversed about her, and it is not a few, speak of her as a woman of handsome talents, good morals, a dutiful wife and an affectionate parent. She is now much out of health; She has several children; her husband is a good sort of a man, ‘tho of small force in business; they have a few acres of poor land which they cultivate, but they are really poor. She told me, she had no doubt that her ill health is in consequence of her being exposed when she did a soldiers duty; and that while in the army, she was wounded. We commonly form our idea of the person whom we hear spoken off, whom we have never seen; according as their actions are described, when I heard her spoken off as a soldier, I formed the idea of a tall, masculine female, who had a small share of understanding, without education, & one of the meanest of her sex. When I saw and discoursed with I was agreeably surprised to find a small, effeminate, and conversable woman, whose education entitled her to a better situation in life. I have no doubt your humanity will prompt you to do all in your power to get her some relief; I think her case much more deserving than hundreds to whom Congress have been generous. I am sir with esteem & respect your humble servant,

Paul Revere”

The following year Sampson was finally awarded a pension and eventually won a general service pension in 1821.

Sampson died of yellow mountain fever in April of 1827 and was buried in Rock Ridge cemetery in Sharon, Mass. After her death, several statues and monuments were erected in her honor in Sharon and a local chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution war name after her. Sampson is considered a Daughter of Liberty due to her role in the Revolutionary War.

In 1982, the Massachusetts legislature declared Sampson the official state heroine and declared May 23 “Deborah Sampson Day.” On that day, reenactors often dress up in Deborah Sampson costumes and perform demonstrations about her.

Sources:

Gannet Sampson, Deborah and Herman Mann. The Female Review: Or, Memoirs of an American Young Lady (Deborah Sampson), Whose Life and Character are Peculiarly Distinguished, Being a Continental Soldier for Nearly Three Years, in the Late American War. 1797

Miskolcze, Robin. Women and Children First: Nineteenth Century Sea Narratives & American Identity. University of Nebraska Press, 2007

Young, Alfred. Masquerade: The Life and Times of Deborah Sampson, Continental Soldier. Vintage Books, 2005

Weston, Thomas. The History of the Town of Middleboro, Massachusetts, Volume I. Houghton Mifflin and Company, 1906

Carreiras, Helena. Women in the Military and Armed Conflict. VS Verlag fur Sozialwissenschaften, 2008

Taylor, Alan. Writing Early American History. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005

“Biography: Deborah Sampson.” Freedom: A History of U.S., PBS, www.pbs.org/wnet/historyofus/web02/features/bio/B01.html

“Deborah Sampson, Soldier in Disguise.” Massachusetts Historical Society, www.masshist.org/object-of-the-month/objects/deborah-sampson-soldier-in-disguise-2005-03-01

Keiter, Jane.”Deborah Sampson, Continental Soldier.” The Westchester Historian, Volume 76, Issue No.1, 2000, http://www.westchesterhistory.com/index.php/publications/best

“Deborah Sampson.” Canton Massachusetts Historical Society, www.canton.org/samson

Moody, Pauline. “Deborah Sampson.” Sharon Historical Society, sharonhistoricalsociety.org/All_Else/All_Pages/DEBORAH%20SAMPSON.pdf

“Deborah Sampson.” National Women’s History Museum, www.nwhm.org/education-resources/biography/biographies/deborah-sampson/

“Deborah Sampson: How She Served as a Soldier in the Revolution.” New York Times, 8 Oct. 1898, query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?_r=1&res=9402E3D71139E433A2575BC0A9669D94699ED7CF&oref=slogin

This website is so awesome. I learned a lot and it was so interesting. Everything was true and I think that this is a great website.

Laura p

Cool

Minions4ever

Cool

This website is very helpful for my presentation that I am doing.

Thank you for that I am also doing a presentation on Deborah Sampson

Hi Sally, thank you for your comment. I hope your presentation goes well.

me too ! i can relate so much

what a cool website now I could do great on my project.

this was perfect for my research.

This is an amazing site. I am doing a Wax Museum project and this will definitely give me facts to help.

awesome website dude!

Well um This stuff was ok but I needed a little bit more information about Deborah Sampson instead of her family and other things. So i don’t think I would give you a 100% but maybe a 70%.

Family was important because it tells you who is related to who and how her family sucseed in life so i give it a 100%

helped me so much 🙂

this has helped me so much! doing both my history papers and this has been awesome reading. thanks man!

You’re welcome, Dane!

Thank you so much for writing this story. I’m in the 7th grade and I’m in an advanced class and we have this really big project on some famous person. We have a 4 page essay that needs to be done as well. This was so helpful thank you so much.

You’re welcome, Madi!

I agree! This information was very useful for my report!

Who is the publisher of this site? (For citing)

Hi Simone, I am the publisher of this site.

This is everything i needed for my R war project

this is great!

This is an awesome website and has everything I need for my report!!!

this helped me reannan and cade so much thank u

You’re welcome, Logan!

this website helped me cade and raeann on are solcil studies slides.

Thanks for the information Now I will get a good grade for my project!!!!!!

Hi! Thanks for posting this info about Deborah Sampson! It really helped me with my project.

Hey, I’m doing a project for 80 points and this is very Helpful, for me I know that I will do great on my test.

I hope you got a one hundred!!