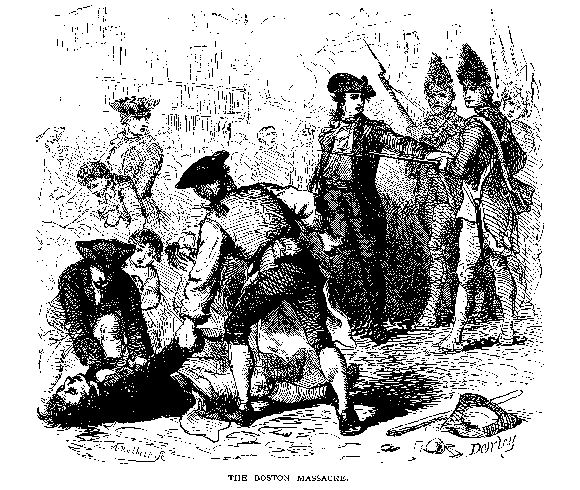

After five people were shot dead by British soldiers during the Boston Massacre in 1770, many patriot leaders used the tragedy to stir up hostility against the British government.

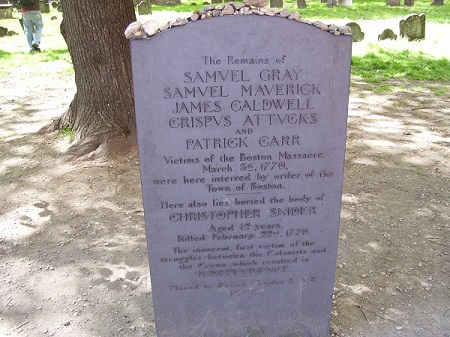

Samuel Adams tugged at the heart strings of the public by holding a public funeral for the five victims and portrayed them as martyrs of a brutal regime before burying them in Granary Burying Ground and erecting a marker “as a momento to posterity of that horrid massacre,” according to the book Samuel Adams: The Life of an American Revolutionary.

The irony was that many in the crowd outside the State House that night were poor, underprivileged minorities and immigrants often ignored in the hierarchy of Boston society.

John Adams, hoping to downplay the image of a lawless city during the Boston Massacre trial, described the crowd as working class outsiders who were “most probably a motley rabble of saucy boys, negroes and mulattoes, Irish teagues and outlandish jack tarrs.”

These words were a direct reference towards the very victims themselves; a rope maker named Samuel Gray, a teenaged apprentice named Samuel Maverick, an Irish immigrant named Patrick Carr, a “mulatto” seaman named Crispus Attucks and a young mariner named James Caldwell.

Adams tried to discredit and blame the victims for the massacre, particularly Attucks, who’s “mad behavior, in all probability, the dreadful carnage of that night is chiefly ascribed.”

When the last victim, Patrick Carr, gave a deathbed confession forgiving the soldiers for their actions, Samuel Adams, unhappy that his martyr forgave his killers, called him an Irish “papist” who died in confession to the Catholic church.

On the day of the victim’s funeral, shops were closed and church bells tolled while ten thousand people attended the funeral and watched as the victim’s bodies were carried by horse-drawn hearse to Granary Burying Ground.

Newspapers covered the funerals extensively, stating:

“The procession began to move between the hours of four and five in the afternoon, two of the unfortunate sufferers, viz. Messrs. James Caldwell and Crispus Attucks who were strangers, borne from Faneuil Hall attended by a numerous train of persons of all ranks; and the other two, viz. Mr. Samuel Gray, from the house of Mr. Benjamin Gray (his brother) on the north side the Exchange, and Mr. Maverick, from the house of his distressed mother, Mrs. Mary Maverick, in Union Street, each followed by their respective relations and friends, the several hearses forming a junction in King Street, the theatre of the inhuman tragedy, proceeded from thence through the Main Street, lengthened by an immense concourse of people so numerous as to be obliged to follow in ranks of six, and bought up by a long train of carriages belonging to the principal gentry of the town. The bodies were deposited in one vault in the middle burying ground. The aggravated circumstances of their death, the distress and sorrow visible in every countenance, together with the peculiar solemnity with which the whole funeral was conducted, surpass description.”

After the funeral, John Hancock, asked fathers across New England to tell their children the story of the massacre until “tears of pity glisten in their eyes, and boiling passion shakes their tender frames,” according to the book Samuel Adams: A Pioneer in Propaganda.

Samuel Adams even arranged an annual celebration each year on the anniversary of the massacre, during which one patriot shouted “The wan tenants of the grave still shriek for vengeance on their remorseless butchers.”

Residents in the North End also marked the occasion by placing illuminated images of the victims in their windows for passersby to see.

The reality is that as members of the lower class, if these victims had died under any other circumstances, their deaths would have been considered insignificant and gone overlooked.

It was solely the political circumstances surrounding their deaths that led to their martyrdom and drew the attention of Samuel Adams and the public.

The Boston Massacre victims are buried at the Granary Burying Ground on Tremont Street, Boston, Mass.

Sources:

Alexander, John K. Samuel Adams: the Life of an American Revolutionary. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2002

Kidder, Frederic and John Adams. History of the Boston Massacre, March 5, 1770. Joel Munsell, 1870

Miller, John C. Samuel Adams: Pioneer in Propaganda. Stanford University Press, 1936