Have you ever wondered why the Boston Massacre is called a massacre? Although the British never called the event by that name, Boston leaders immediately began calling it a “massacre” after the event occurred on March 5, 1770.

The reason it is believed Boston officials called it a “massacre” was to use it as propaganda in order to inflame public opinion and capitalize on colonial resentment of the British.

One of the first instances of the event being called a massacre is in a newspaper article about it, which was published in the Boston Gazette and Country Journal on March 12, 1770.

The article described the event as “this horrid massacre” and also described the victims as “the unhappy victims who fell in the bloody massacre of the Monday evening preceding.”

About a week later, the first official colonial report on the massacre was published as a pamphlet and was titled A Short Narrative of the Horrid Massacre in Boston.

The report was compiled between March 13 and March 19 by James Bowdoin, Joseph Warren and Samuel Pemberton after they had been appointed by Boston officials to do so at a town meeting on March 12, 1770.

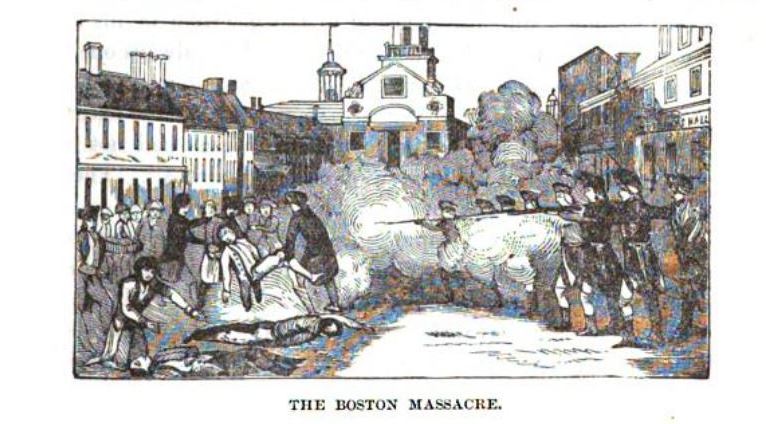

To further drive home the point, the frontispiece of the pamphlet (the illustration facing the title page) was an engraving by Paul Revere titled “Bloody Massacre Perpetrated in King Street in Boston” which depicted a line of soldiers firing into a crowd of unarmed civilians.

Revere wasn’t even the first illustrator to call the event a massacre since he had actually taken the idea for the image and its title from Henry Pelham.

In mid-March, Henry Pelham himself had created a line drawing of the event, which he titled “The Fruits of Arbitrary Power, or the Bloody Massacre” and had given it to Revere so he could create a print of it.

Revere essentially copied Pelham’s work and created his own nearly identical engraving and even gave it a similar name, once again using the word “Bloody Massacre” in the title.

What Did the British Call the Boston Massacre?

The British called the Boston Massacre the “unhappy disturbance” and the “incident on King Street” and other words to that effect.

In Captain Thomas Preston’s account of the event, which was published in a British newspaper called the Public Advertiser on April 28, he referred to it as “the melancholy affair” and as “the affair” while describing his surprise at the “suddenness of my trial after the affair while the people’s minds are all greatly inflamed.”

In May of 1770, a pamphlet about the event was published in London and was titled A Fair Account of the Late Unhappy Disturbance at Boston in New England.

The pamphlet included eyewitness accounts of the event that corroborate the soldier’s claim that they were attacked by an unruly mob.

The pamphlet did not approve of the colonist’s use of the word “massacre” to describe the event, calling it an abuse of language:

“This is the whole of what the Boston Narrative calls the horrid Massacre. How far it deserves that appellation, let the unprejudiced reader judge. For my part, I cannot but think it a very gross abuse of language, and highly injurious to the unhappy officer and soldiers who were concerned in this affair, to call it by the same name that has heretofore been used to describe such wanton, unnecessary, and premeditated acts of general destruction as the slaughter of the Protestants of France in the year 1572, and of the Protestants of Ireland in 1641; to which a resistance made by twelve soldiers against more than an hundred people armed with sticks and bludgeons, in defence of a post which it was their duty to defend, seems to me to bear no resemblance.” (“A Fair Account” 19.)

Was the Boston Massacre Really a Massacre?

Merriam-Webster dictionary defines a massacre as “the act or an instance of killing a number of usually helpless or unresisting human beings under circumstances of atrocity or cruelty.”

Seeing that the Boston Massacre was an event involving a number of unruly protestors and rioters who were holding clubs and sticks and throwing snowballs and ice at the soldiers, they were not “helpless or unresisting human beings” and it therefore does not meet the defintion of a “massacre.”

When the case finally went to trial in October of 1770, John Adams served as the soldier’s lawyer and defended them by arguing that the incident was actually a riot.

Adams even quoted an English legal text that defined rioters as “more than three persons” using force and violence to accomplish an end, upon which Adams asked the jury:

“Were there not more than three persons in Dock Square? Did they not agree to go to King Street, and attack the main guard? Where then, is the reason for hesitation, at calling it a riot? If we cannot speak the law as it is, where is our liberty?” (Allison 43.)

Furthermore, Adams argued that the law clearly states that, in such a situation, the soldiers had the right to defend themselves with force.

He argued that the law states that if the soldiers had been assaulted and their lives were in danger “they had a right to kill in their own defense” but if their lives were not in danger yet they were being struck by the mob than this was enough to reduce the sentence to manslaughter.

In the end, the jury agreed with Adams and six of the soldiers were acquitted and two were found guilty of manslaughter.

Sources:

Allison, Robert J. The Boston Massacre. Commonwealth Editions, 2006.

“A Fair Account of the Late Unhappy Disturbance at Boston in New England.” Massachusetts Historical Society, masshist.org/database/viewer.php?item_id=386&pid=3

“A Short Narrative of the Horrid Massacre in Boston.” Massachusetts Historical Society, masshist.org/database/viewer.php?item_id=337&pid=2