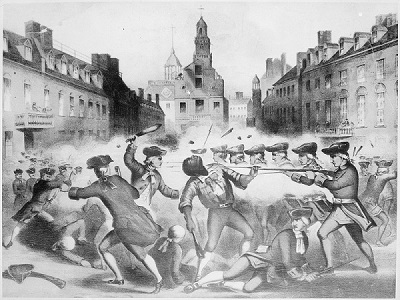

The Boston Massacre was an event that occurred in Boston during the American Revolution. It is believed to be one of many events that caused the American Revolution.

The following are some facts about the Boston Massacre:

What Was the Boston Massacre?

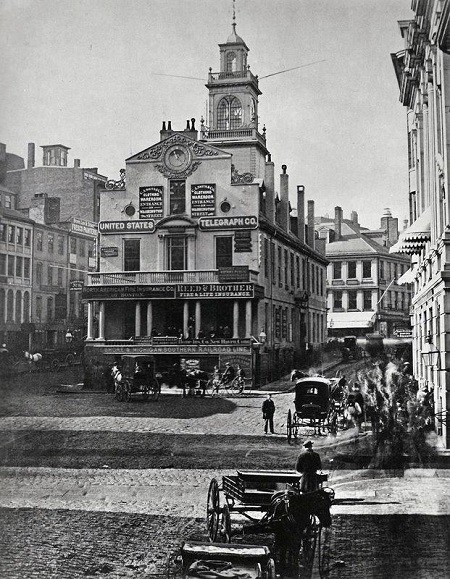

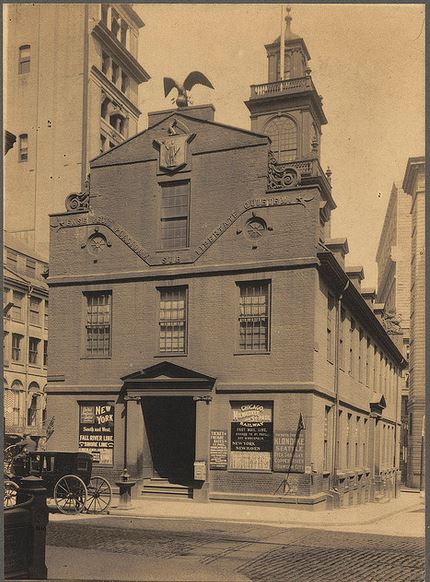

The Boston Massacre was a riot that began when a group of 50 citizens gathered outside of the State house to protest the large presence of British soldiers in the city. Five colonists were killed during the riot.

The soldiers had been sent to Boston to protect customs commissioners as they enforced the recent, and highly unpopular, Townshend acts, which placed an import tax on goods such as tea, glass, paper and other products from England.

What Year Was the Boston Massacre?

The Boston Massacre occurred on the night of March 5, 1770

What Caused the Boston Massacre?

The massacre began when the group started to hassle the lone sentry, Private White, standing on guard outside of the State house.

When a citizen named Edward Garrick insulted the soldier’s commanding officer, White left his sentry box and hit Garrick in the face with his rifle, enraging the crowd even further.

As the crowd swelled, Captain Thomas Preston arrived with more soldiers to reinforce Private White but could not control the crowd or persuade them to leave.

The citizens began to throw snowballs, rocks and sticks at the soldiers. Witnesses say when a sentry named Private Montgomery was struck in the face with a stick, he fired his gun into the crowd. More objects were thrown and more shots were fired.

When the skirmish was over, three people lay dead: an escaped slave, named Crispus Attucks, who worked as a sailor on a whaling ship, a rope maker named Samuel Gray and a mariner named James Caldwell, and eight others were wounded.

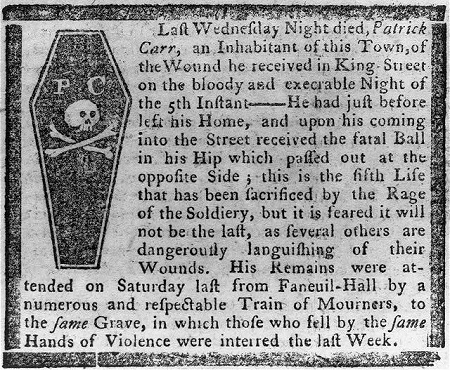

Two of the wounded, Samuel Maverick and Patrick Carr, later died of their injuries. Samuel Adams held funerals for the Boston Massacre victims who were then buried in Granary Burying Ground where they remain today.

Within a few hours of the massacre, Captain Preston and the soldiers were jailed. Knowing the danger they faced, Captain Preston prepared his account of the events, which was published in a London newspaper called the Public Advertiser the following month and then republished in newspapers throughout Boston:

“…The mob still increased, and were more outrageous, striking their clubs or bludgeons one against another, and calling out, ‘Come on, you rascals, you bloody backs, you Lobster Scoundrels; fire if you dare, G-d damn you, fire and be damn’d; we know you dare not;’ and much more such language was used…While I was thus speaking, one of the soldiers, having received a severe blow with a stick, stept a little on one side, and instantly fired, on which turning to and asking him why he fired without orders, I was struck with a club on my arm, which for some-time deprived my of the use of it; which blow, had it been placed on my head, most probably would have destroyed me. On this general attack was made on the men by a great number of heavy clubs, and snow-balls being thrown at them, by which all our lives were in imminent danger; some persons at the same time from behind calling out, ‘Damn your Bloods, why don’t you fire?’ Instantly three or four of the soldiers fired, one after another, and directly after three more in the same confusion and hurry…The whole of this melancholy affair was transacted in almost 20 minutes. On my asking the soldiers why they fired without orders, they said they heard the word “Fire,” and supposed it came from me. This might be the case, as many of the mob called out “Fire, fire,” but I assured the men that I gave no such order, that my words were, ‘Don’t fire, stop your Firing!'”

The Boston Massacre Trial:

Fearing the soldiers would not get a fair trial, Governor Thomas Hutchinson delayed the trial until the fall in order to give the citizens of Boston time to calm down.

John Adams, Robert Auchmuty Jr., and Josiah Quincy Jr. served as the soldier’s lawyers while Robert Treat Paine and Samuel Quincy served as the prosecution.

A decision was made to try Preston separately from the soldiers to prevent them from turning on Preston and each other in order to save themselves, according to an article in the American Bar Association journal:

“Were the officer [Preston] to be tried in the same proceedings with the men, the resultant mutual finger-pointing might well convince the jury to find all the defendants guilty. Perhaps in part to avoid this difficulty the decision was taken to at some time to sever [separate] the trials.”

Preston’s trial began on October 24th at 8 a.m. Many eyewitnesses gave testimony at the trial, yet the accounts contradict one another, making the matter even more confusing. One eyewitness, Daniel Cornwall, testified that Preston ordered the troops not to fire:

“Captain Preston was within two yards of me and before the men and nearest to the right and facing the Street. I was looking at him. Did not hear any order. He faced me. I think I should have heard him. I directly heard a voice say “Damn you, why do you fire? Don’t fire”. I thought it was the Captain’s then. I now believe it.”

Yet, another eyewitness, Charles Hobby, testified that he clearly heard Preston give the order to fire:

“Captain Preston was then standing by the soldiers, when a snow ball struck a grenadier, who immediately fired, Captain Preston standing close by him. The Captain then spoke distinctly, “Fire, Fire!” I was then within four feet of Capt. Preston, and know him well. The soldiers fired as fast as they could one after another. I saw the mulatto [Crispus Attucks] fall, and Samuel Gray went to look at him, one of the soldiers, at a distance of about four or five yards, pointed his piece directly for the said Gray’s head and fired. Mr. Gray, after struggling, turned himself right round upon his heel and fell dead.”

At the end of the trial, on October 30th, Preston was acquitted of all charges after the evidence failed to establish whether he gave the order to fire.

According to the article in the American Bar Association journal, the outcome of the trial is not actually surprising considering that most of the jurors were loyalists and/or acquaintances of Captain Preston:

“’The management to pack the jury,’ a radical partisan wrote, ‘was evident to every impartial spectator.’ This is not an exaggeration. Of the twelve jurors, five, Philip Dumaresq, Gilbert Dublois, William Hill, Joseph Barrick and William Wait Wallis, were later loyalist exiles. The available evidence indicates that these men were supporters of Preston and the King well before the trial. Dumaresq, for example, was ‘an intimate aquiantance’ of Preston’s. Hill was a baker who supplied the British Fourteenth Regiment its bread. Barrick boasted of his open avowal of support. Deblois’s case is even more interesting, as Preston pointed out in the 1780s when testifying on the juror’s behalf to the board of commissioners appointed to examine the losses sustained by the American loyalists: ‘The testimony of Thomas Preston…Sheweth that he knew Gilbert Deblois Merchant in Boston…That when said Preston was thrown into jail there, for what was call’d the bloody massacre, said Deblois got him several valuable evidences, and gave him the character of many of the persons returned for jurors, by which means he was enabled to set aside most of those return’d by the town, who were men of violent principles, and pick out some of the moderate ones sent up from the country. That on a deficiency of jurors said Deblois attended, and got himself put on the pannel, where during the tryal which lasted a week, he was confin’d in the jail along with the other jurors, to the great neglect of his business. That by his strict attention and close examination he detected some of the evidences of perjury; and also that by his personal influence on the rest of the jurors he was a great means of said Prestons being acquitted.’”

The remaining soldier’s trial began on November 27. During John Adams’ closing statement, he painted the soldiers as peacekeepers and the victims, particularly Crispus Attucks, as violent troublemakers who were solely to blame for the shootings, according to the book The History of the Boston Massacre:

“Bailey ‘saw the mulatto [Crispus Attucks], seven or eight minutes before the firing, at the head of twenty or thirty sailors in Cornhill, and he had a large cord-wood stick.’ So that this Attucks, by the testimony of Bailey, compared with that of Andrew and some others, appears to have undertaken to be the hero of the night, and to lead this army with banners. To form them in the first place in Dock Square, and march them up to King street with their clubs. They passed through the main street up to the main guard in order to make the attack. If this was not an unlawful assembly, there never was one in the world. Attucks, with his myrmidons, comes around Jackson’s corner and down to the party by the sentry-box. When the soldiers pushed the people off, this man, with his party, cried, Do not be afraid of them; They dare not fire; kill them! kill them! knock them over! And he tried to knock their brains out. It is plain, the soldiers did not leave their station, but cried to the people, Stand off! Now, to have this reinforcement coming down under the command of a stout mulatto fellow, whose very looks was enough to terrify any person, what had not the soldiers then to fear? He had the hardiness enough to fall in upon them, and with one hand took hold of a bayonet, and with the other knocked the man down. This was the behavior of Attucks, to whose mad behavior, in all probability, the dreadful carnage of that night is chiefly to be ascribed.”

Yet, Adams also reminded the jurors to focus on the evidence and not to let their emotions about the shootings blind their judgement:

“Facts are stubborn things; and whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or the dictates of our passions, they cannot alter the state of facts and evidence: nor is the law less stable than the fact; if an assault was made to endanger their lives, the law is clear, they had a right to kill in their own defence; if it was not so severe as to endanger their lives, yet if they were assaulted at all, struck and abused by blows of any sort, by snow-balls, oyster-shells, cinders, clubs, or sticks of any kind; this was a provocation, for which the law reduces the offence of killing, down to manslaughter, in consideration of those passions in our nature, which cannot be eradicated. To your candour and justice I submit the prisoners and their cause. The law, in all vicissitudes of government, fluctuations of the passions, or flights of enthusiasm, will preserve a steady, undeviating course; it will not bend to the uncertain wishes, imaginations and wanton tempers of men.”

Six of the soldiers, William Wemms, John Carroll, William McCauley, William Warren, Hugh White and James Hartigan, were found not guilty and two, Hugh Montgomery and Matthew Kilroy, were convicted of manslaughter since they were the only soldiers that witnesses saw firing.

The soldiers narrowly escaped the death penalty through a legal loophole, known as the “benefit of clergy” which exempted clergymen, including men with the ability to read or recite biblical passages, from secular courts. The “clergymen’s” penalty for manslaughter was branding on the thumb.

On December 14th, Kilroy and Montgomery were brought back to the court, where they read a passage from the Bible and were branded on the hand with the letter “M,” for manslaughter, with a glowing hot iron.

Adams later stated, during a conversation in 1822, that both men cried before they were branded, according the Massachusetts Historical Society website:

“I never pitied any men more than the two soldiers who were sentenced to be branded in the hand for manslaughter. They were noble, fine-looking men; protested they had done nothing contrary to their duty as soldiers; and, when the sheriff approached to perform his office, they burst into tears.”

Tension between British soldiers and colonists settled in Boston after the trials, at least temporarily. Samuel Adams successfully campaigned to turn March 5th into a day of mourning marked with fiery, commemorative speeches each year, which continued until 1784.

In 1887, a marker dedicated to the victims of the massacre was placed on the exact spot where Crispus Attucks fell.

Due to construction and urban renewal projects, the Boston Massacre marker was moved many times over the years but still remains in the general area where the massacre occurred.

The massacre didn’t always go by that name and was originally referred to by Paul Revere as the Bloody Massacre in King Street.

For more information about the Boston Massacre, check out this timeline of the Boston Massacre.

Sources:

“The Boston Massacre.” The Freedom Trail Foundation, www.thefreedomtrail.org/freedom-trail/boston-massacre.shtml

“The Boston Massacre.” The Massachusetts Historical Society, www.masshist.org/revolution/massacre.php

“Adams Papers.” Massachusetts Historical Society, www.masshist.org/publications/apde2/view?id=ADMS-05-03-02-0001-0001

Wroth, Kevin L. and Hiller B. Zobel. “The Boston Massacre Trials.” American Bar Association Journal, 55, April 1969, pp: 329-333

Kidder, Frederick and John Adams. The History of the Boston Massacre, March 5, 1770. J. Munsell, 1870

What a great article! Thank you so much for explaining history in such an interesting way. Without taking away any relevant bits, you’ve made this snapshot of history into an intriguing story that will *stick*. You’re a good teacher!

Thank you for the kind words, Janeen!

And if I am not mistaken, the image of the Boston Massacre was run on the front page of the Boston Gazette, the newspaper of my ancestor. Benjamin Edes, my great grandfather six generations back.