Salutary neglect was an unofficial British policy in the colonies that greatly affected Massachusetts in 18th century.

The policy was an intentional lack of enforcement by the British government of British trade laws in the American colonies.

The phrase salutary neglect itself comes from a speech given by Edmund Burke at the House of Commons on March 22, 1775, during which he stated:

“That I know that the colonies in general owe little or nothing to any care of ours, and that they are not squeezed into this happy form by the constraints of watchful and suspicious government, but that, through a wise and salutary neglect, a generous nature has been suffered to take her own way to perfection; when I reflect upon these effects, when I see how profitable they have been to us, I feel all the pride of power sink, and all presumption in the wisdom of human contrivances melt, and die away within me.”

“Edmund Burke.” Illustration published in a Pictorial History of the United States circa 1852

Period of Salutary Neglect:

Although many historians believe the British government started to loosen its hold over the colonies around 1690, the period most associated with salutary neglect took place in the mid-1700s.

For most of the 17th century the British government had no official policies in place regarding the colonies. The companies, merchants and independent corporations in the colonies governed themselves with very little supervision from British officials.

The Old Wharf at Salem, Mass, illustration published in the New England Magazine, circa March 1914

This changed in 1651 when the Navigation Act was passed. It was one of the first laws on trade regulation in the American colonies.

The law required that all goods shipped to and from the American colonies had to be carried on English ships.

This was an attempt at prohibiting colonists from engaging in trade with other countries besides England, according to the book Wars of the Age of Louis XIV:

“The Navigation Act’s immediate object was mundane: to stop the Dutch from carrying fish and other colonial products to England, and to compel Italian merchants to ship their raw silk on English rather than Dutch ships. Other products targeted by the Act were Turkish weaves, Spanish wool, colonial wines, and Neapolitan olive oil…Longer term, and more fundamentally, the Navigation Act liberated internal trade within a previously closed English system, disallowing old royal monopolies and exclusive charter companies, and eroding patronage systems in favor of freer (but not free) trade and a wider commercial sense of the ‘national interest.’”

The Navigation Act was primarily aimed at the Dutch, whom had colonized what is now New York state and had a monopoly in the North American trade industry.

This act consisted of a series of acts: the Navigation Act of 1651, the Navigation Act of 1660, the Navigation Act of 1663 and the Navigation Act of 1696.

The additional Navigation Acts continued the policies of the 1651 act by adding to the list of items that could only be shipped on English ships, which included sugar, tobacco, cotton-wool, indigo, ginger, fustic and etc and requiring ships heading to the American colonies to first stop at English ports for inspection and payment of extra duties.

Despite passing the Navigation Act, the British government rarely enforced it in the colonies, mostly because it was difficult to do so.

The colonies had ports all along the colonial coastline which would have required the government to send over a large number of customs officials to regulate.

As a result, American colonists ignored the law and continued to smuggle goods and trade regularly with both the Dutch and the French West Indies.

Although it was unenforced, the Navigation Act of 1651 was a contributing factor in the First Anglo-Dutch war of 1652-1654, which was a naval war between the English and the Dutch over North American trade routes and colonial land.

The Navigation Act also caused a ripple effect in the colonies when the war it started led to tension in the New England Confederation, an alliance formed between the New England colonies to help bolster colonial defenses.

In the 1680s, the British government made a significant, yet flawed, attempt to strengthen its control over the colonies by revoking the Massachusetts Bay Colony’s charter as punishment for disobeying its orders and combined all of the New England colonies into one mega colony called the Dominion of New England.

The goal of the Dominion of New England was to strengthen colonial defenses, appoint government officials in the colonies and help enforce the Navigation Act.

The problem was the mega colony was too large to run effectively and it quickly came to an end in 1689 after news of the Glorious Revolution in England prompted the rebellious colonists to overthrow the Dominion officials.

The new King and Queen of England, Mary and William of Orange, made the Massachusetts Bay Colony a royal colony in 1691 and issued it a new charter with stricter rules than the original charter.

These changes caused a lot of unrest and anxiety in the Massachusetts Bay Colony and many historians believe it was one of the many underlying factors in the Salem Witch Trials of 1692.

After Robert Walpole took over as the Lord of the Treasury in 1721, a major change happened regarding colonial trade regulation and the government began to avoid enforcing trade laws.

It is believed that Walpole, who served from 1721 to 1742, and the Duke of Newcastle, who served as the secretary of state for the southern department from 1724 to 1748 were the creators of the salutary neglect policy.

Walpole’s main goal in office was to increase taxable wealth in England to help pay off debts occurred during various wars against Spain and France. Newcastle’s job was to manage commercial relations between England, the British colonies in North America and the Caribbean.

Walpole and Newcastle had three main interests in colonial governance, according to the book An Economic History of the United States:

1. A source of patronage to help maintain a majority of supporters in Parliament

2. increased revenue by taxing increasing amounts of of colonial products entering England

3. increasing exports of manufactured products to the colonies in order to increase employment in Britain

To accomplish these goals, Walpole discouraged enforcing trade laws and regulations in the colonies and encouraged the policy of salutary neglect, stating: “If no restrictions were placed on the colonies, they would flourish,” according to the book Conceived in Liberty:

“Salutary neglect had meant the conscious thwarting of Britain’s grand mercantilist design for controlling and restricting American commerce and industry for the benefit of British merchants and manufacturers. Furthermore, the Walpole-Newcastle policy of laissez-faire toward the colonies had allowed the representative colonial assemblies to wrest effective power from royally appointed governors by wielding the power of the purse over colonial taxes and appropriations, notably including the governor’s own salaries. Thus, from 1720 through the 1750s, the American colonies were virtually de facto independent of British imperial control, an independence bolstered by a libertarian spirit and ideology eagerly imbibed from the radical libertarian English writers and journalists of the period.”

Yet, according to another book, Events That Changed America in the Eighteenth Century, this neglect wasn’t entirely deliberate and may have mostly been caused by the fact that British officials at the time were simply too busy and incompetent to effectively regulate the American colonies:

“Historians have pointed to a variety of institutional and personal factors to explain the relatively hands-off policies of the Walpole years. The Board of Trade, the body principally responsible for enforcement of mercantilist legislation, was in an institutionally weak position from the end of the seventeenth century, becoming weaker in policy decisions especially after 1714, and it would only become an effective enforcer of the law when reorganized in 1748. Newcastle, as Secretary of State (Southern Department), came to the post without preparation on the details of the system, resulting in a suspension of much administrative activity while he learned the duties of his office after 1724. Even after that, however, enforcement was very lax, and Newcastle’s preferred approach to problems was to delay firm action. James Henrietta, in his account of Newcastle’s political career, attributes the ‘salutary neglect’ of the era to a combination of accidental factors – ‘administrative inefficiency, financial stringency, and political incompetence’ – as well as to some element of deliberate policy.”

End of Salutary Neglect:

The era of salutary neglect officially come to an end in the 1760s.

In February of 1763, the Seven Year’s War came to an end. Around the same time, in April of 1763, the new Prime Minister, George Grenville, came into office. Both of these events contributed to the end of salutary neglect.

During the Seven Year’s War the British government incurred a large amount of debt fighting France for control of North America and needed a way to pay it off.

In addition, Grenville decided to increase the number of British troops in North America to help defend them from any continued threat from France.

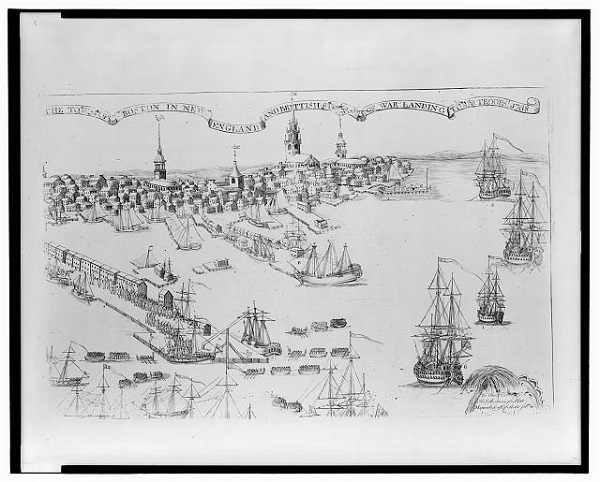

The town of Boston in New England and British ships of war landing their troops! 1768, illustration by Paul Revere, circa 1770

Grenville decided that since the colonists directly benefited from this defense of the British army, they should help pay for the cost of the army.

To raise revenue, Grenville mandated that the British government should shift some of the cost of the war to the American colonies by restructuring colonial governance and increasing national revenue.

Grenville proposed a series of new taxes on top of the Navigation Acts and the Trade Acts: the Sugar Act of 1764, the Currency Act of 1764 and, later, the Stamp Act of 1765, which all came to be known as the Grenville Acts.

Colonists didn’t approve of these new taxes and, at a town meeting on May 24, 1764, they proposed to fight the Grenville Acts by signing a Non-importation Agreement, in which they pledged to boycott most British goods.

In reaction to the boycott, Parliament passed a new tax law: the Stamp Act of 1765, which placed a tax on all paper used for printed materials in the colonies.

Parliament also passed the Quartering Act of 1765, which forced colonists to personally house and feed the British soldiers sent to the colonies.

Effect of Salutary Neglect and its End:

The British policy of salutary neglect toward the American colonies inadvertently contributed to the American Revolution.

This was because during the period of salutary neglect, when the British government wasn’t enforcing its laws in the colonies, the colonists became accustomed to governing themselves.

According to the book, Divided Loyalties, it was the years of salutary neglect and self-governing that actually helped American colonists develop their sense of independence and self-sufficiency:

“In Walpole’s day the colonists, left to their own devices, got along as he knew they could. With a minimum of interference from London they had for years been exercising the mechanics of self-government, learning as they went, discovering through trial and error what worked and what did not, while growing ever so slowly into entities capable for the most part of running their own affairs.”

Not only did the colonists become used to governing themselves due to salutary neglect, they also didn’t feel that Parliament had the authority to govern them anymore.

The colonists felt they could only be represented in Parliament by politicians they actually voted for, hence their “no taxation without representation” motto that became popular during the American Revolution.

Grenville disagreed and felt that although the colonists didn’t personally elect the politicians in Parliament, those politicians still served as their “virtual representation” rather than their “actual representation.”

When the government used this argument to begin buckling down on the colonies, the colonists resented it and, realizing they were powerful enough to fight back, they resisted.

Groups such as the Sons of Liberty and the Daughters of Liberty, which formed in protest of the new taxes, sprouted up in Boston and then spread to other cities and colonies.

Riots and protests broke out in Boston, particularly the Stamp Act riots in August of 1765, the Boston Massacre in March of 1770, which began as a protest against the presence of British troops in the city, and the Boston Tea Party in December of 1773.

This all created a very volatile situation in the American colonies and eventually sparked the Revolutionary War, which broke out after the Shot Heard Round the World was fired in April of 1775.

Sources:

“Office of the Historian: French and Indian War/Seven Year’s War, 1754-1763.” Office of the Historian, U.S. Department of State, n.d., history.state.gov/milestones/1750-1775/french-indian-war

“Overview of the State of Pre-Revolutionary American Maritime Commerce.” Mariner’s Museum and Park, n.d., www.marinersmuseum.org/sites/micro/usnavy/02.htm

“The Navigation Act 1651.” BCW Project, n.d., bcw-project.org/church-and-state/the-commonwealth/the-navigation-act

Nolan, Cathal J. Wars of the Age of Louis XIV, 1650-1715: An Encyclopedia of Global Warfare and Civilization. Greenwood Press, 2008.

Events that Changed America in the Eighteenth Century. Edited by John E. Findling, Frank W. Thackeray, Greenwood Press, 1998.

Ketchum, Robert M. Divided Loyalties: How the American Revolution Came to New York. Henry Holt and Co, 2002.

Rothbard, Murray Newton and Leonard P.G. Liggio. Conceived in Liberty. Vol. 1, Arlington Publishers House, 1975.

Henretta, James A. Rebecca Edwards, Robert O. Self. America: A Concise History, Combined Volume. Bedford / St. Martins, 2012.

Seavoy, Ronald. An Economic History of the United States: From 1607 to the Present. Routledge, 2006.

Axelrod, Alan. The Real History of the American Revolution: A New Look at the Past. Sterling Publishing, 2007.

McNeese, Tim. American Colonies. Lorenz Educational Press, 2002.