Massachusetts colonists were the first to fight in the Revolutionary War and they also made up the majority of the soldiers in the war. They served as militiamen, minutemen and soldiers in the Continental Army.

Massachusetts Militiamen & Minutemen:

The first minutemen of the American Revolution were organized in Worcester county, Mass in September of 1774 when officials at the Worcester County Convention decided to weed out loyalists in the militia by requiring the resignation of all officers and then reconstituting the militia into seven regiments with new officers.

Officials then called for each regiment to put aside one-third of its regiment to form into new, special companies called minutemen. These men were expected to keep their arms and equipment with them at all times and be ready to march at a minute’s warning.

A handful of other counties voluntarily adopted this policy and when the Massachusetts Provincial Congress met in Salem in October of 1774 it urged all counties to adopt the policy.

The first test of the minutemen was at the Battle of Concord and the Battle of Lexington on April 19, 1775, during which hundreds of minutemen battled British troops on the Lexington Green and at the Old North Bridge in Concord.

Revolutionary War battle between civilians and British soldiers. illustration by Felix Octavius Carr Darley. circa 1840-1888

Although the minutemen lost the Battle of Lexington, they won the Battle of Concord and drove the British troops back to Boston where the state militia blockaded the troops in Boston, in what later became known as the Siege of Boston.

The minuteman units were later abandoned when the Continental Army was established in June of 1775 but the state militia continued.

Notable Massachusetts militiamen and minutemen in the Revolutionary War:

Colonel John Allan

Aaron Bancroft

Supply Belcher

Sergeant William Berry

Thaddeus Bowman

Colonel Roger Brown

John Brown of Pittsfield

Stephen Bullock

John Buttrick

Thomas Carpenter III

George Claghorn

Elijah Crane

Phelix Cuff, an African-American man from Waltham

Timothy Danielson

Isaac Davis

Thomas Dawes

William Dawes

Prince Estabrook, an African-American from Lexington

Christian Febiger

Brigadier General Nathaniel Freeman

Joseph Frye

Thomas Gardner

Toby Gilmore

Baxter Hall

John Hancock

John Hannum III

Lemuel Haynes

George Robert Twelves Hewes

Samuel Hildreth

Cyprian Howe

Rufus King

Joseph Leavitt

Barzillai Lew

Benjamin Lincoln

Levi Lincoln Sr.

Moses Little

Solomon Lovell

George Middleton

William Munroe

John Nixon

Samuel Osgood

Joseph Palmer

John Parker

Timothy Pickering

Asa Pollard

Seth Pomeroy

Salem Poor, an African-American from Andover

Seth Read

Paul Revere

Caleb Rich

Deborah Sampson, a woman from Plympton who disguised herself as a man

Job Shattuck

David Shepard

Thomson J. Skinner

Abraham Somes

William Stacy

Russell Sturgis

Bezaleel Taft Sr

Samuel Taft

Ebeneezer Thayer

Anselm Tupper

Benjamin Tupper

Royall Tyler

Joseph Bradley Varnum

Peleg Wadsworth

James Warren

Joseph Warren

Simeon Wheelock

Samuel Willard

Benjamin Ruggles Woodbridge

Was Paul Revere a Minuteman?

Contrary to popular opinion, Paul Revere was not a minuteman but he did warn the minutemen, during his famous Midnight Ride, that the British troops were approaching Concord on the night of April 18/19 in 1775.

Paul Revere later served as a Lieutenant Colonel in the Massachusetts Militia but was court-martialed in 1779 for disobey orders during the failed Penobscot Expedition in Maine. Revere was later cleared of all charges in 1782.

Massachusetts Continental Army Soldiers:

When the Continental Army was first established in June of 1775, out of the 37,363 soldiers who enlisted in the first year, about 16,449 were from Massachusetts.

This is not that surprising though since the American Revolution began in Massachusetts and it was the first colony to be occupied by the British.

However, in almost every year of the Revolutionary War, the majority of soldiers in the Continental Army were from Massachusetts, according to Ainsworth Rand Spofford in his book Massachusetts In The American Revolution:

“Thus, in 1777, long after the evacuation of Massachusetts by the enemy, we find that 12,591, out of 68,720 troops enlisted, were from Massachusetts; being a larger number than any other state contributed. The same lead was maintained throughout the war, except in 1779 and 1780, when Virginia’s soldiers and military actually in the field exceeded those of Massachusetts by a few hundred, while in 1782 (which witnessed the virtual close of the struggle), Massachusetts put 4,423 men in the field, out of a total of 18,006 in the Continental Army, Virginia having only 2,204 at the same period…Other regions witnessed more decisive battles, and continued for a much longer time, the immediate theatre of war; but Massachusetts soldiers marched or sailed to every colony, and bore their part in every important battle, from Bunker Hill down to Yorktown.”

Among these 68,720 Massachusetts soldiers, about 1,700 were African American and Native American men. These soldiers fought in the some of the most important battles of the Revolutionary War, such as Battle of Bunker Hill in June of 1775 where 150 African-American soldiers served.

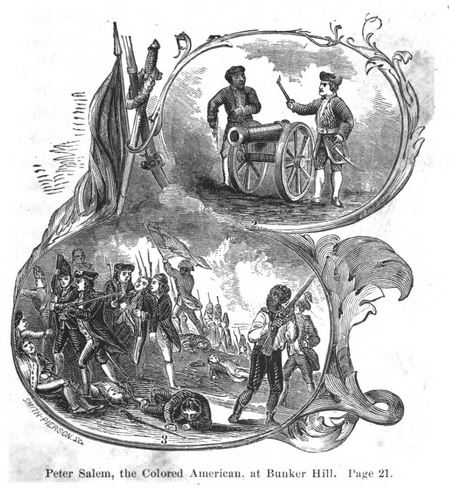

Peter Salem at Bunker Hill, illustration published in The Colored Patriots of the American Revolution, circa 1855

When George Washington later prohibited the enlistment of African-American men in the Continental Army, in November of 1775, the matter was taken up by Congress who declared on January 15, 1776:

“That the free negroes who have served faithfully in the army at Cambridge may be reenlisted therein, but no others.”

That year Massachusetts set its own criteria for the enlistment of African Americans by passing two acts in 1776. The first was passed on January 26 and the second of November 14 which specifically exempted “Negroes, Indians and mulattoes” from military service in the Massachusetts militia.

This didn’t seem to stop Massachusetts African-Americans from enlisting though, according to the book Forgotten Patriots: African-American and American Indian Patriots in the Revolutionary War by Eric G. Grundset:

“It is evident that in spite of the resolutions passed in 1776, Massachusetts African Americans were already serving in the army. A June 1, 1777 muster roll of Captain Charles Colton’s 2nd Company in Colonel John Greaton’s 3rd Massachusetts Regiment included the names of eleven African American men, most of who had enlisted prior to the January 27 act. The Baroness von Riedesel, who was among a group of American-held prisoners being escorted through western Massachusetts in the fall of 1777, wrote in a letter, ‘…you do not see a regiment in which there is not a large number of blacks…’”

When Massachusetts began having a hard time meeting the State’s quota for the army set by Congress, the legislature passed another act on January 27, 1777, that exempted only Quakers.

Finally, on April 28, 1778, the Massachusetts legislature passed a law officially allowing the enlistment of African-Americans.

Some Massachusetts African-Americans who served in the Continental Army were:

Peter Salem of Framingham

Pomp Jackson of Newburyport

Cato Prince of Marblehead

Felix Cuff of Waltham

Primus Jackall of Palmer

Pelatiah McGoldsmith of Palmer

What Type of Uniforms Did Massachusetts Soldiers Wear?

Minutemen were citizen soldiers and didn’t have an official uniform so they instead wore regular clothing, which consisted of waistcoats, linen hunting shirts and breeches.

American soldiers early in the war wore long, brown coats. When the Continental Army’s uniforms were standardized in 1779, each regiment was assigned a blue coat with facings of a particular color to indicate their regiment. The New England states of Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Connecticut, and Rhode Island wore blue coats with white facings.

For more information on this topic, check out the following article What Type of Uniforms Did Revolutionary War Soldiers Wear?

Lists of Massachusetts Revolutionary War Soldiers:

The names of all of the Massachusetts soldiers who served in the Continental Army are too numerous to list here but the following books and websites have partial and/or complete lists:

♦ Massachusetts Sailors and Soldiers in the Revolutionary War: Volume 1-17.

♦ A List of the Soldiers in the War of the Revolution, from Worcester, Mass: With a Record of their Death and Place of Burial. Worcester by Mary Cochran Dodge

♦ Soldiers of Oakham, Massachusetts in the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812, the Civil War by Henry Parks Wright

♦ “Massachusetts Revolutionary War Soldiers 1775-1783.” ma-roots.org. Kathy Leigh.

www.ma-roots.org/military/revwar

Sources:

Nell, William Cooper. The Colored Patriots of the American Revolution. Boston, Robert F. Wallcut, 1855.

Grundset, Eric G. Forgotten Patriots: African-American and American Indian Patriots in the Revolutionary War. National Society Daughters of the American Revolution, 2008.

Hartgrove, W. B. “The Negro Soldier in the American Revolution.” The Journal of Negro History, vol. 1, no. 2, 1916, pp. 110–131, www.jstor.org/stable/3035634.

Bell, J.L. “The Massachusetts Militia, and Its Exceptional Men.” Boston 1775, 4 Aug. 2017, boston1775.blogspot.com/2017/08/the-massachusetts-militia-and-its.html

“The Battle of Bunker Hill Has a Diverse History.” African American Registry, www.aaregistry.org/historic_events/view/battle-bunker-hill-has-diverse-history

“African Americans and the End of Slavery in Massachusetts – Revolutionary Participation.” Massachusetts Historical Society, www.masshist.org/endofslavery/index.php?id=56

Odle, Cliff. “Brothers in Arms: African American Soldiers in the American Revolution.” The Freedom Trail Foundation, www.thefreedomtrail.org/educational-resources/article-brothers-in-arms.shtml

Collins, Elizabeth M. “Black Soldiers in the Revolutionary War.” U.S. Army, 27 Feb. 2013, www.army.mil/article/97705/Black_Soldiers_in_the_Revolutionary_War

Grundset, Eric G. “African-Americans of Massachusetts in the Revolution.” Massachusetts Society Sons of the American Revolution, 20 June. 2013, www.massar.org/african-americans-of-massachusetts-in-the-revolution/

“African Americans During the Revolutionar War – Teacher Reference Sheet.” The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 2006, www.history.org/history/teaching/enewsletter/volume5/images/reference_sheet.pdf

Leigh, Kathy. “Massachusetts Revolutionary War Soldiers 1775-1783.” Massachusetts Roots, Feb. 2002, www.ma-roots.org/military/revwar/

“Minutemen.” Encyclopedia Britannica, www.britannica.com/topic/minuteman

“Who Were the Minutemen?” National Park Service, www.nps.gov/mima/learn/education/who-were-the-minute-men.htm

Spofford, Ainsworth R. Massachusetts In The American Revolution. Washington D.C.: District of Columbia Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, 1895.

Excellent! I am a lover of history, and especially of the American Revolution.

I live on Massachusetts Ave (previously MENOTOMY Way during the Revolution. We live several doors away from the Jason Russell House, site of the bloodiest battle of the first day of the American Revolution.

Visitors can see the holes in the wall from the British musket fire. The home now serves as a museum. The retreating British set fire to many homes in the area. Arlington’s Meeting House/Church was next door. The retreating British stole silver from the home including the silver clockworks in a beautiful clock. The silver was later taken back from the British.

It is a great museum stop. You can see the written roll call of the Menotony. (Now named Arlington) Minuteman who reported when Paul Revere stopped here on the evening of his ride!