The Boston Massacre was an event that occurred in Boston during the American Revolution. It took place on the evening of March 5, 1770 during a protest in front of the Custom House in Boston, Massachusetts. The massacre was one of many events believed to have caused the American Revolution.

It is important to know the timeline of the massacre because it helps to put the event into context so we can understand why and how it happened.

The following is a timeline of the Boston Massacre:

1768:

- In October, British troops arrive in Boston to enforce the Townshend Acts.

1770:

- On February 22, a 11-year-old boy named Christopher Seider is shot and killed by Ebenezer Richardson, a British customs official, after Richardson tried to stop a group of school boys from throwing rocks at the shop of a loyalist merchant. One of the rocks strikes Richardson and the crowd chases him home where he fires his musket out the window and strikes Seider. The shooting sparks outrage in Boston.

- On February 26, Seider’s funeral is held at Faneuil Hall. Around 2,000 people follow Seider’s casket during the procession, which starts at Faneuil Hall, goes down around the Liberty Tree near Boston Common, back to the Old State House and then to the Granary Burying Ground where the boy is laid to rest.

- On March 2, a British soldier from the 29th Regiment, Patrick Walker, is walking past John Gray’s ropewalk when one of the workers asks him if he wants a job. When he replies yes, the man jokes that he can clean his outhouse. A fight breaks out between the men, Walker flees and then returns several times with 20 and then 30 British soldiers but they are chased away by the rope workers each time.

- In the afternoon on March 3, another fight breaks out between three British soldiers and a group of rope workers at Archiebald McNeil’s ropewalk.

- On March 4, Lieutenant Colonel Maurice Carr of the 29th Regiment orders a search of Gray’s ropewalk for a missing sergeant that Carr suspects may have been murdered there but finds nothing. Rumors begin to swirl that trouble is brewing between the soldiers and rope workers and several fights break out between the two groups throughout the city.

- On the morning of March 5, a handbill reportedly signed by the soldiers of the 14th and 29th Regiment is posted throughout Boston warning the “rebellious people of Boston” that the soldiers were joining forces to “defend themselves against all who shall oppose them.”

- At 3pm on March 5, a crowd of 300 townspeople gather at the Liberty Tree.

- Around 6pm – 7pm on March 5, small groups of three to six townspeople are seen walking the streets of Boston armed with clubs.

- At 7pm on March 5, a group of townspeople gather around Hugh White, a British sentry standing guard outside the Custom House, and begin throwing snowballs and ice at him. White warns the group to leave him alone and a man in a red cloak approaches the group, speaks to them and they then cross the street and keep their distance.

- At 8pm on March 5, a crowd of men and boys armed with shovels, sticks and swords gather in Dock Square where some of them break into Faneuil Hall and tear apart a butcher’s stall to make clubs out of the wood.

- At 8:30pm on March 5, the crowd in Dock Square has grown to 200 to 300 men and an unknown man in a red cloak and white wig begins to whip the crowd into a frenzy before the crowd splits up into three groups, of about 100 people each, and march off in different directions. One group heads to the main barracks where the 29th Regiment are housed. Unable to break through the gates or taunt the soldiers into coming out of the barracks, the crowd eventually moves on to King Street.

- In front of the Custom House, the crowd begins to harass White again and he retreats to the steps of the Custom House for safety.

- At 9pm on March 5, the Brattle Street Church bell begins to ring and people spill out into the street looking for a fire.

- In the North End, a group of 25 to 30 men, including Crispus Attucks and Partrick Keaton, respond to sound of the bell and join the crowd in front of the Custom House. Attucks is carrying two clubs and hands one to Keaton who throws it in the snow.

- William Jackson, an importer and British sympathizer, rushes to the tavern where Captain Thomas Preston is lodging to tell him what’s happening.

- Preston rushes to the main barracks and gathers Corporal William Wemms and six privates, Hugh Montgomery, James Hartigan, William McCauley, John Carroll, William Warren and Matthew Kilroy, who form two lines and march down King Street to the Custom House.

- Wemms leads the soldiers through the crowd to the steps of the Custom House while the crowd throws snowballs, ice and oyster shells at them.

- Knowing that the soldiers are forbidden to fire their weapons until they have read the Riot Act to crowd, the crowd begin to taunt the soldiers to fire their guns.

- A colonist named Benjamin Burdick, armed with a club and a broadsword, taunts Private Montgomery who pushes him back with his bayonet and Burdick pushes away the bayonet with his sword which hits the gunlock.

- At that exact moment, Montgomery is struck by a piece of wood thrown by someone in the crowd.

- As Montgomery staggers, Crispus Attucks grabs for Montgomery’s bayonet but Montgomery recovers his footing, raises his gun and fires. At the same moment, another soldiers fires his gun as well.

- Attucks is struck by two musket balls in the chest and another person in the crowd, Samuel Gray, has his head partially taken off by one of the musket balls. They both fall dead in the street.

- Preston responds by yelling “Why did you fire?” at the soldiers at which point the other soldiers hear the word “fire” and three of them fire into the crowd as well.

- One of the musket balls hits sailor James Caldwell, who is walking across King Street, in the back and he falls dead in the street.

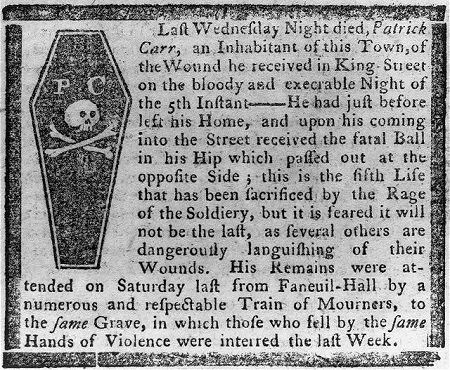

- The crowd begins to move in on the soldiers but they fire again. Robert Patterson and merchant Edward Payne are struck in the arm, apprentices Christopher Monk and John Clark are also hit and Patrick Carr, who is across the street in Quaker Lane, is struck in the hip. Another musket ball ricochets off a building and hits apprentice Samuel Maverick in the chest. Two other muskets balls hit tailor John Green and apprentice David Parker in the legs.

- Governor Thomas Hutchinson hurries from his home near North Square to King Street where he reprimands Preston for allowing his soldiers to fire on the crowd and orders him to take the soldiers back to the barracks.

- Hutchinson makes his way for the Old State House and go upstairs to the council chamber where he steps out on the balcony, surveys the scene and orders the crowd to go home. He also sees the soldiers outside the guardhouse aiming at the crowd and orders the soldiers to go inside.

- On the morning of March 6, Samuel Maverick dies of his wound. Captain Preston surrenders and Wemms, the six privates and Hugh White are arrested.

- On March 8, a funeral procession is held for Crispus Attucks, Samuel Maverick, James Caldwell and Samuel Gray. The individual processions start from various homes of the victim’s family or friends in Boston, except for Crispus Attucks’s procession which starts from Faneuil Hall, and converge on King Street before continuing on to Main Street (modern-day Washington Street), down to the Liberty Tree, onto Boston Common and then to the Granary Burying Ground where they are all laid to rest in one grave.

- On March 10, Preston publishes a letter thanking the Boston public for the manner in which he was treated on March 5.

- Between March 12 – 15, depositions are taken defending the seven British soldiers.

- On March 12, a town meeting is held during which James Bowdoin, Joseph Warren and Samuel Pemberton are appointed to write a report on the Boston Massacre.

- On March 13, a grand jury indicts Thomas Preston, William Wemms, and the seven privates in the murders of the Boston Massacre victims.

- On March 14, Patrick Carr dies of his wound.

- On March 16, customs commissioner John Robinson sails from Boston, Mass to London, England carrying the depositions and Preston’s account of the massacre.

- Between March 13 – 19, justices of the peace, Richard Dana and John Hill, take depositions from 96 witnesses while Colonel Darlympe, deputy customs collector William Sheaffe and Bartholomew Green cross-examine the witnesses. From the depositions, Bowdoin, Warren and Pemberton write an official town report on the event, titled Short Narrative of the Horrid Massacre in Boston, Perpetrated in the Evening of the Fifth Day of March 1770, By Soldiers of the 29th Regiment. The report blames the soldiers as well as the custom commissioners for the violence.

- On March 19, the report is accepted during a town meeting and copies are ordered so it can be sent to influential men in England such as Parliament member Isaac Barre, former governor Thomas Pownall, and Benjamin Franklin, who is representing the colonial assemblies in London.

- On March 19, a grand jury indicts Ebenezer Richardson in the death of Christopher Seider and charges George Wilmot as his accomplice.

- In mid-late March, Engraver Henry Pelham creates a drawing of the Boston Massacre, titled The Fruits of Arbitrary Power, which depicts Captain Preston with his sword raise in command while his soldiers fire in unison into a crowd of peaceful, unarmed civilians. In the window of the Custom House a puff of smoke is depicted, suggesting a customs commissioner also fired on the crowd.

- Pelham presented his drawing to silversmith Paul Revere who creates a new engraving, titled The Bloody Massacre perpetrated in King Street, Boston, on March 5th 1770 by a party of the 29th Regt, which depicts essentially the same image but with slight variations, such as the words “Butcher’s Hall” written across the front of the Custom House and a gun with a cloud of smoke sticking out of the building’s window.

- On March 29, Pelham writes to Revere and accuses him of copying his drawing.

- On April 1, Captain Andrew Gardner sails from Boston to England carrying the official report on the Boston Massacre. Upon reaching England, the news of the Boston Massacre is widely reported in the British newspapers.

- On April 20, the trial of Ebenezer Richardson and George Wilmot for the murder of Christopher Seider begins and ends the same day.

- On April 21, Richardson is found guilty and Wilmot not guilty.

- On April 28, Preston’s account of the Boston Massacre is published in a London newspaper, the Public Advertiser, under the title Case of Captain Preston of the 29th Regiment.

- In May, an anonymous author in London produces a pamphlet, titled A Fair Account of the Late Unhappy Disturbance at Boston in New England, which includes the fight at Gray’s ropewalk and draws on depositions from the soldiers, townspeople and also containes Andrew Oliver’s account of a March 6th meeting of the Governor’s Council in which a plan is discussed to try and remove the troops and customs commissioners.

- On June 18, British newspaper reports of Preston’s account of the Boston Massacre reach Boston, Mass and are reprinted in the local papers.

- On September 7, the Massachusetts General Court bring charges against Preston, Wemms and the seven privates.

- In October, the Governor’s Council launch an investigation into Oliver’s account and decide that he misrepresented their March 6th meeting and committed a breach of trust by sending the minutes of their meetings to London. The council sends the report to their own agent in England seeking action against Oliver.

- On October 24, the trial of Captain Preston begins at the Queen Street Courthouse in Boston.

- On October 27, the closing arguments in Preston’s trial are heard.

- At 8am on October 30, Captain Preston is acquitted of all charges after the evidence fails to establish whether he gave the order to fire.

- On November 27, the trials of the remaining soldiers begin at the Queen Street Courthouse.

- On December 3, the closing arguments in the soldier’s trial are heard.

- On December 5, six of the soldiers, William Wemms, John Carroll, William McCauley, William Warren, Hugh White and James Hartigan, are found not guilty and two soldiers, Hugh Montgomery and Matthew Kilroy, are convicted of manslaughter since they were the only soldiers that witnesses saw firing. To prevent Montgomery and Kilroy from being hanged, they plead the benefit of the clergy, a medieval provision which claimed clergymen were outside the jurisdiction of secular courts, but since the defense could only be used once the accused had to be branded on the thumb.

- On December 14, Kilroy and Montgomery were brought back to the court, where they read a passage from the Bible and are branded on the hand with the letter “M,” for manslaughter, with a hot iron.

- The soldiers return to their regiment, which is now stationed in New Jersey, and Preston sails for England.

1771:

- On the evening of March 5, on the first anniversary of the Boston Massacre, a commemorative lecture is held at the Manufactory House, bells toll between 9pm and 10pm and Paul Revere illuminates his windows with scenes from the massacre, which depicts images of a wounded Christopher Seider and the wounded Boston Massacre victims.

1772:

- On March 5, an even larger commemoration is held at the Old South Meeting House. A pamphlet, titled A Monumental Inscription on the Fifth of March, is published that day which mentions that Ebenezer Richardson has still not been hanged for his crime and includes Revere’s engraving of the massacre.

- On March 9, Governor Hutchinson pardons Ebenezer Richardson. Richardson flees Boston, with an angry mob in pursuit, but he escapes unharmed and never returns to Boston.

1773:

- On March 5, the annual Boston Massacre commemoration is held at the Old South Meeting House and Dr. Joseph Warren delivers the lecture that evening after John Adams declined an invitation to do so.

1774:

- On March 5, the annual commemoration is held at the Old South Meeting House and John Hancock delivers the lecture that evening.

1775:

- On March 5, the annual commemoration is held at the Old South Meeting House and Dr. Joseph Warren delivers the lecture that evening.

1776:

- On March 5, the annual commemoration is held in Watertown, because Boston is occupied by the British army due to the Siege of Boston, and Peter Thatcher delivers a lecture on Dr. Joseph Warren’s death at the Battle of Bunker Hill in June of 1775.

- On March 16, the Siege of Boston ends and the British army leave Boston.

1777:

- On March 5, the annual commemoration is held in the Old Brick Meeting House because the Old South Meeting House was badly damaged by the British army, who turned it into a riding school, during the Siege of Boston. All future Boston Massacre commemorations are held at the Old Brick Meeting House.

1783:

- On March 5, a town meeting votes to move the annual Boston Massacre commemoration from March 5 to July 4 to celebrate national independence. The Boston Massacre begins to fade from the public’s memory.

1855:

- An African-American scholar named William Cooper Nell publishes his book, Colored Patriots of the American Revolution, which discusses Crispus Attucks and the Boston Massacre and sparks a renewed interest in the historical event.

1857:

- On March 5, the African-American community in Boston holds its first annual Crispus Attucks Day rally at Faneuil Hall.

1887:

- A marker dedicated to the Boston Massacre is placed on the corner of State and Exchange Street on what is believed to be the exact spot where Crispus Attucks fell dead.

1888:

- On November 14, a dedication ceremony is held for a newly constructed Boston Massacre Monument on Boston Common.

1904:

- The Boston Massacre marker on the corner of State and Exchange Street is removed to make way for construction on the Boston subway and the marker is relocated across the street near the site where James Caldwell was killed.

1960s:

- The Boston Massacre marker is removed again due to an urban renewal project and is relocated to a traffic island in front of the Old State House.

2011:

- The Boston Massacre marker is removed again in order to upgrade the State Street subway station and is relocated to its current location at the intersection of Congress, Devonshire and State Streets.

If you want to read more about the American Revolution, check out this article on the best books on the American Revolution.

Sources:

Allison, Robert. The Boston Massacre. Applewood Books, 2006.

Hinderaker, Eric. Boston’s Massacre. Harvard University Press, 2017.

Publications of the Colonial Society of Massachusetts, Volume 7. Colonial Society of Massachusetts, 1895.

“To Benjamin Franklin from the Massachusetts House of Representatives, 6 November 1770.” Founders Online, founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-17-02-0165