The Siege of Boston took place in Boston during the Revolutionary War.

The siege was the beginning phase of the Revolutionary War, during which American militiamen surrounded and trapped the British army inside Boston.

How Did the Siege of Boston Begin?

The siege began on April 19, 1775, when British troops retreated to Boston after the Battles of Lexington and Concord, during which the Shot Heard Round the World had taken place, and ended on March 17, 1776 when the British finally fled Boston by sea.

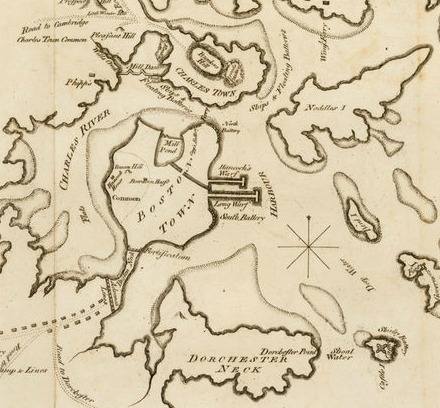

The siege began when American militiamen blocked off Boston neck and Charlestown neck, the thin strips of land connecting the Boston and Charlestown peninsulas to the mainland, to prevent the British from conducting anymore attacks on the surrounding countryside.

Since the rebels lacked a navy, the British army still retained control of Boston harbor, yet supplies in the town quickly dwindled as they awaited the arrival of supply ships.

During the first few days of the 11-month long siege, any movement in or out of the city, whether it be military or civilian, was completely cut off.

On April 22, British General Thomas Gage met with town officials to work out a deal that would allow civilians to leave or enter Boston, according to the book After the Siege: A Social History of Boston 1775-1800:

“Believing himself best rid of troublemakers who had ‘hostile intentions against his Majesty’s troops,’ General Gage at first moved to accelerate the evacuation of the city. In a meeting on April 22 between Gage and town officials, both sides agreed that ‘the women and children, with all their effects, shall have safe conduct without the garrison’ and that male inhabitants ‘upon condition…that they will not take up arms against the King’s troops’ would also be permitted to leave…All possessions except plate and firearms could be taken from the town. General Gage assured those civilians desiring to stay that they would receive his protection. At a town meeting the following day the inhabitants agreed to the terms…Between late April and early June a mass exodus occurred. Within eight weeks approximately ten thousand inhabitants fled Boston. Confused, terrified, uncertain as to the state of events, inhabitants gathered what possessions they could. Now refugees, they fled along the crowded roads throughout the surrounding countryside seeking places of refuge…As thousands of terrified Bostonians fled the town, Loyalist refugees from throughout Massachusetts, clinging to entry passes from the Provincial Congress, poured into Boston seeking refuge in an otherwise hostile world. Many left behind pillaged homes, the remnants of months of persecution from their Whig neighbors…Across the narrow neck of the Boston peninsula, in the shadow of the town gallows and the fort that British soldiers were busily erecting, both Whig and Tory sympathizers passed. One might only imagine the mixture of anger, resentment, fear, and melancholy that each of them faced as they looked at the thousands around them pulling carts and carrying in their arms and on their backs the few possessions with which they were allowed to depart. ‘You can have no conception of the distresses [of] the people,’ wrote one observer. ‘You’ll see parents that are lucky enough to procure papers, with bundles in one hand and a string of children in the other…wandering out of the town…not knowing whither they’ll go…’ The previous day he informed a friend, ‘If I can escape with the skin of my teeth, [I] shall be glad, as I don’t expect to be able to take more than a change of apparell with me.’ Lives were turned upside down: some would never see their homes again.”

During the siege, General Thomas Gage decided to fortify Boston’s hills and defensible positions to strengthen his hold over Boston. Gage ordered a line of 10 twenty-pound guns at Roxbury neck and fortified four of the nearby hills, yet decided to abandon Charlestown and Dorchester heights.

Map of Boston, by John Almon, drawn at Boston in June 1775, published in London Aug 28 1775

The Battle of Chelsea Creek:

On May 14, in an attempt to deprive the British army’s foraging parties of much needed resources and supplies, the Massachusetts Committee of Safety issued the following order:

“Resolved, as their opinion, that all live stock be taken back from Noddle’s Island, Hog Island, Snake Island, and from that part of Chelsea near the sea coast, and be driven back, and that the execution of this business be committed to the committee of correspondence and selectmen of the towns of Medford, Malden, Chelsea, and Lynn, and that they be supplied with such a number of men, as they shall need, from the regiment now at Medford.”

On May 27 and 28, this order led to what became known as the Battle of Chelsea Creek, but is sometimes referred to as the Battle of Noddle’s Island or the Battle of Hog Island.

The battle broke out between American troops and British troops when the Americans removed all of the livestock from the harbor islands and burned the hay the British needed to feed their animals.

After spotting smoke from the burning hay, the British ship HMS Diana went to investigate but became stuck in the marsh during the early morning hours of May 28th.

The American troops began to attack the ship and, after the British sailors were quickly rescued by another British ship, the American troops boarded the HMS Diana, stripped it of valuables and munitions and set it on fire. This was the first naval engagement of the Revolutionary War.

The American troops later returned to Noddle Island, on May 29 and 30, to remove the remaining livestock and attempted to make the island inhabitable for the British by burning down a mansion on the island, owned by fellow patriot Henry Howell Williams, which left his family destitute.

The American troops later tried to occupy the island themselves but were bombarded by the British fleet on June 3rd. After another skirmish on June 10, both sides decided to abandon the island and it became something of a no-man’s land during the rest of the siege.

The Battle of Bunker Hill:

In June, the arrival of British reinforcements prompted the British army to make plans to reclaim Dorchester and Charlestown in an attempt to break the siege.

General Thomas Gage knew that to keep control of Boston, the British army needed to have control of the hills of Dorchester and Charlestown, which not only overlooked the tiny peninsula of Boston and the harbor on both sides but also nearby rebel posts in Roxbury and Cambridge.

On June 15, the Committee of Safety learned of the British army’s plans in Charlestown and issued an order for troops to immediately fortify Bunker Hill and Dorchester Heights, according to the book Battle of Bunker Hill:

“Whereas, it appears of importance to the safety of this colony that possession of the hill called Bunker’s Hill, in Charlestown, be securely kept and defended; and, also, some one hill or hills on Dorchester neck be likewise secured: therefore, resolved, unanimously, that it be recommended to the Council of War that the above-mentioned Bunker’s Hill be maintained, by sufficient forces being posted there; and as the particular situation of Dorchester Neck is unknown to this committee, they advise that the Council of War take and pursue such steps respecting the same as to them shall appear to be for the security of this colony.”

Although the original order was to fortify Bunker Hill, the American troops quickly decided to fortify nearby Breed’s hill instead, most likely due to its close position to the harbor, over the course of the night on June 16th.

As the sun rose on June 17th, the British troops saw the fortifications on the hill and fired upon it from their ships, as well as with their battery of guns and howitzers on nearby Copp’s hill.

By the afternoon, British troops arrived in Charlestown and moved in to attack. Although the American troops successfully repelled the British army’s first two attempts to take the hill, they were defeated on the third attempt and were forced to retreat into Cambridge.

Although the Battle of Bunker Hill was a technical victory for the British, they suffered heavy casualties, with nearly 268 dead and 828 wounded, which bolstered the American’s confidence.

To make matters worse for the British, the victory did very little to weaken the rebel posts around the city.

Yet, the colonists suffered their own losses at Bunker hill, particularly when the British army burned Charlestown to the ground in an attempt to control sniper fire coming from the town and when noted patriot Dr. Joseph Warren was killed by a bullet during the retreat. Warren quickly became a martyr for the cause.

After the Battle of Bunker Hill, the siege essentially became a stalemate with very little activity besides a few skirmishes and raids.

On July 5, the Continental Congress adopted the Olive Branch Petition, hoping to prevent the conflict from escalating into an official war, and sent it to London, where it arrived in September, but King George III rejected it and refused to read it.

On July 10, after British troops made an advance across Boston neck into Roxbury, American troops responded by attacking British troops staying at nearby Brown’s tavern and set the building on fire.

On August 2, British troops killed and hanged the body of an American rifleman, prompting the Americans to retaliate with gun fire, according to the book 1776:

“His comrades, seeing this, were much enraged and immediately asked leave of the Gen to go down and do as they pleased. The riflemen marched immediately and began operations. The regulars fired at them from all parts with cannon and swivels, but the rifleman skulked about, and kept up their sharpshooting all day. Many of the regulars fell, but the riflemen only lost one man.”

On August 23, after hearing news of the Battles of Lexington, Concord and Bunker Hill, King George III issued the Proclamation of Rebellion, which stated that in light of “various disorderly acts committed in disturbance of the publick peace, to the obstruction of lawful commerce, and to the oppression of our loyal subjects,” the colonists were deemed to be at war with the British government and must be subdued by military force.

On August 30, British troops raided Roxbury. While one group of American troops defended Roxbury, another 300 American soldiers launched an attack on Lighthouse Island, during which they killed several British soldiers and took 23 soldiers prisoner.

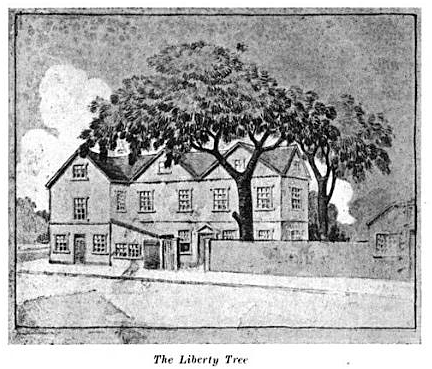

The Liberty Tree:

Also, on one of the last few days of August, British troops and Loyalists led by Job Williams attacked and cut down the famous Liberty Tree near Boston Common, which was a meeting place for the Sons of Liberty and had become a symbol for resistance against the British government, according to the book, Celebration of the Centennial Anniversary of the Evacuation of Boston:

“Under the branches of the tree matters of public concern were discussed during the stirring times which preceded the actual commencement of hostilities, and many of the prominent actors in the Revolutionary conflict took a lively part in the proceedings. The tree was cut down in August, 1775, by the Tories and British troops, much to the vexation of the patriots who remained in the town during the siege. While the tree was being cut down, a soldier, in attempting to remove a limb, fell and was killed. Alluding to the event, the ‘Essex Gazette,’ of August 31st, 1775, says, ‘Armed with axes, they made a furious attack upon it. After a long spell of laughing and grinning, sweating, swearing, an foaming, with malice diabolical, they cut down a tree because it bore the name liberty.’ A freestone bas-relief, set in the front of the building on the corner of Essex and Washington streets, marks the spot where the tree stood.”

Vandalizing and looting was a common occurrence during the siege, despite the fact that the British troops were strictly ordered not to do it, according to the book, The Hundreds of Boston Orators Appointed by the Municipal Authorities and Other Public Bodies from 1770 to 1852:

“Notwithstanding the regulars were strictly forbidden to destroy houses, fences or trees, during the siege, they demolished the steeple of Rev. Dr. Howard’s Church, suspecting that it had been used as a signal staff; converted the edifice into a barrack, demolishing the pews; the Old South was used as a riding-school; Dr. Stillman’s church was converted into a hospital; the Old North was demolished for fuel; ‘although there were large quantities of coal and wood in town,’ and Brattle-street church was used as a barrack. The regulars commenced destroying the fences around Hancock’s mansion; but Gage prevented it, on the complaint of the selectmen. But their direst vengeance was against Liberty Tree, when one of the regulars, in attempting to dismantle its branches, fell on the pavements, and was instantly killed. Dr. Pemberton relates that the enterprise of destroying the Liberty Tree was under the direction of Job Williams, a tory refugee from the country.”

The British began making plans to abandon Boston and move onto New York, which they believed would make a better base for their military operations, before winter set in but communication problems and a lack of transport large enough to move their troops and accompanying loyalists delayed these plans.

Liberty Tree, illustration published in A. W. Mann’s “Walks & Talks About Historic Boston”, circa 1917

Both sides decided to hunker down for the winter and waited for spring to arrive. That winter was long and cold with many desertions on both sides of the siege.

Although the American troops were used to the frigid New England winters, many of the British troops had never experienced weather that cold and found it difficult to bear.

The Battle of Dorchester Heights:

The siege finally came to an end in March, after General Washington ordered Henry Knox to bring numerous cannons captured at Fort Ticonderoga to Boston in an attempt to force the British to finally leave the city.

Knox positioned the cannons on Dorchester Heights, aiming them directly at Boston harbor and the British navy.

The British first planned to retaliate by attacking Dorchester Heights but after a storm delayed their attack, they had time to reconsider their plan and realized they were outnumbered, outgunned and could no longer hold the city. This prompted British Commander William Howe to evacuate Boston.

Lord Howe evacuating Boston, engraving by J. Godfrey, circa 1861

The British Evacuate Boston:

After pillaging the city of everything they could steal, the British army had to wait several days for favorable winds but finally left Boston on March 17, which is now known as Evacuation Day, and sailed to Halifax, Nova Scotia, according to the book After the Siege:

“Finally, on March 17 the British departed with more than nine hundred loyalists, a number of them Bostonians. They included a wide variety of individuals traveling in families and alone. Just as royal officials, merchants, doctors, lawyers, and clergymen fled, so did artisans, shopkeepers, widows, and laborers. A few later returned, such as John Gore, father of the future Massachusetts governor and senator, after spending nine years in exile. Most were not welcome. To this end Massachusetts passed a Banishment Act in 1778, ‘to prevent the return to this state of certain persons.’ Confiscation of loyalist property left little for most to return to in any event. How many knew that cold, blustery winter’s day in March as they sailed away from Boston harbor that they were saying good-bye to homes, friends and sometimes family forever?”

British evacuation of Boston, Massachusetts, on March 17, 1776, wood cut, circa 1776

Who Won the Siege of Boston?

The Americans won the Siege of Boston by surrounding the British, cutting off their supply routes and then forcing them to abandon Boston by outgunning them with the captured cannons. This officially brought the Revolutionary War battles in Massachusetts to an end.

Sources:

Frothingham, Richard. Battle of Bunker Hill. Little, Brown & Company, 1890.

Ketchum, Richard M. Decisive Day: The Battle for Bunker Hill. American Heritage Publishing Co, 1962.

Barbara Carr, Jacqueline. After the Siege: A Social History of Boston 1775-1800. UPNE, 2005.

French, Allen. The Siege of Boston. The Macmillan Company, 1911.

McCullough, David. 1776. SImon & Schuster Paperbacks, 2005.

Todd, Geoffrey. Chronicles of the Revolutionary War. AuthorHouse, 2006.

Ellis, George E. Celebration of the Centennial Anniversary of the Evacuation of Boston by the British Army. Rockwell and Churchill, 1876.

Loring, James Spear. The Hundreds of Boston Orators Appointed by the Municipal Authorities and Other Public Bodies, From 1770 to 1852. John P. Jewett and Company, 1852.

Watts, Jenny Chamberlain, William Richard Cutter and Henry Williamson Haynes. A Documentary History of Chelsea: Volume 2. Massachusetts Historical Society, 1908.

Brown, Craig J. Victor T. Mastone and Christopher V. Maio. “The Revolutionary War Battle America Forgot: Chelsea Creek, 27-28 May 1775.” The New England Quarterly, Vol. 86, no. 3, Sept. 2013, pp 398-432.

“Battle of Chelsea Creek.” Mass.gov, Commonwealth of Massachusetts, www.mass.gov/eea/agencies/czm/buar/battle-of-chelsea-creek.html

“Siege of Boston.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, www.history.com/topics/siege-of-boston

“Siege of Boston.” Massachusetts Historical Society, www.masshist.org/online/siege/index.php

I find this site of great interest, as Benjamin Edes of The Boston Gazette and Country Journal was an ancestor of mine, my great grandfather 7 generations back. A number of years ago I obtained a copy of Peter Edes’ journal or diary that he wrote whilst held in Boston Gaol for 105 days. Peter Edes was Benjamin’s son, imprisoned for supposedly possessing firearms, he was arrested with his cousin. From my research, when they were arrested, the supposed measure or penalty was death by hanging, but I am of the opinion that given the circumstances in Boston at the time, this would only inflamed matters even worse, a wise act of caution by the commanding officer. If the outcome of this had been different I would not be here today. I look forward to reading more of your posts.

Thanks, Ben! I’m planning on writing some more articles about Boston during the American Revolution so I’ll keep an eye out for your ancestor in my research.

My GSreatX5 Grandfather, at that time, Minuteman, Lt Benjamin Brown, was among those who removed the livestock from Noodle Island and burned the Packet Diana. He, along with 3 of his brothers participated in the Battle of Bunker Hill and the Siege of Boston. Capt. Brown’s brothers died during that War and Capt Brown went on to settle near Athens Ohio and helped to start the Coonskin Library

Thank you Jack for sharing, your family is filled with honor and has my respect for your families courage.

Great reading. It’s been a few years since I read it, but John Ferling’s “Almost a Miracle” adds some interesting details about this period. Apparently, in the lead-up to the evacuation, Washington wanted to launch an attack on Boston by crossing the frozen Charles River, but was talked out of it in favor of the Dorchester Heights strategy. Once the Heights are fortified, the British threatened to burn Boston if they weren’t allowed to evacuate peacefully.

According to “Lost Boston”, there used to be a plaque at 148 State St. identifying it as the start of Long Wharf, from whence British troops departed Boston (forever!)